Accent on the Fourth Syllable

Dmitri Shostakovich has a name with too many Russian syllables. If I tell you that he was

Although was considered “enemy of the people” during his long career, Shostakovich also received high honors and many stamps have borne his image.

a twentieth-century classical composer you may think of unintelligible dissonance and mostly snob appeal. If I hint that he was the outstanding composer for Soviet Russia, we’re approaching complete obscurity. Yet his life, his music and his astrology are all extraordinary and as an individual – controversial as he continues to be – he qualifies as an exemplary individual whose life can be an inspiration in our age.

Shostakovich was of the first generation of composers born in the twentieth century. He penned a massive quantity of music but is best known for fifteen symphonies and fifteen string quartets which explore vast harmonic and emotional ranges. He also has the karma of producing much of his great work under the shadow of Stalin’s Great Terrors and subsequent repressions. His name will be forever associated with the German siege of Leningrad during World War II. In spite of many obstacles he managed to stay on this planet and compose music until 1975.

Art and Society and Dictatorship

We live in a society with many cultural voices, and not all are positive. Our movies, television, popular music and video, and contemporary art frequently produce works that are banal at best, or sordid and nihilistic and harmful. There are always voices admonishing our culture’s creations for promoting unhealthy development and confused moral standards in adults. We may recall various attempts at censorship over the centuries, and they have not worked very well: culture, like language, is best when it can pursue its own path.

In a controlled society, an authoritarian or totalitarian culture, artistic is

In a totalitarian culture art is at the service of the leadership’s goals and that often makes for bad art.

subordinate to the needs of the society as defined by its leadership. Art not in conformity with those standards may be deemed degenerate and consequences may fall heavily on the artist.

Dmitri Shostakovich, whose professional career endured decades of soviet authoritarianism and who fell out in and out of favor several times during his long career and was his country’s outstanding composer. He produced some of the great classical music of his century, and his life and music will excite and confuse historians and musicologists for generations. His astrology is interesting as well.

The “Shostakovich Wars”

A few years after his death Volkov’s book, based on private interviews with the composer, created quite the stir. In some quarters its authenticity is still questioned, but it contains much of Shostakovich’s candid observations and opinions, many of them harshly criticizing his treatment by the Soviet government.

Stalin had no hesitation about using Shostakovich as a propaganda tool and the composer was often on record dutifully denouncing the “decadent bourgeois tendencies” of contemporary music; the composer developed a mastery parroting the party line when it was necessary. This was internationally on display in 1949 when he visited the United States as Soviet representative to a “Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace”, when he read speeches written for him that denounced the “bourgeois tendencies” in modern Western music, and in particular Russian émigré Igor Stravinsky whose work he generally admired. And there were also those effusive public apologies after his music had been “justly criticized” by his ideological mentors.

Those close to him knew that Shostakovich was no party lackey, but that there was a large gulf between the public pronouncements and his private conversations that would reveal what he truly thought. This also manifested in much of his music: he often managed to con his governmental minders by giving his music a false program when it was obvious that much of it contained irony, satire, and over-blown bombast as a musical response to his government’s actions. Sometimes this did not work well for him.

Shostakovich’s life and musical legacy continue to be assessed and he continues to be subject of controversy. On one matter, though, there is no controversy: he was on the front lines of history as both witness and participant and much of his music is a mirror to that history.

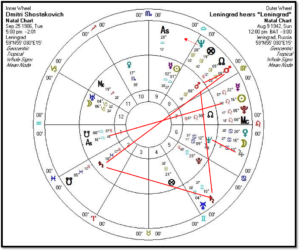

From an astrologer’s point of view, an enigmatic individual like Dmitri Shostakovich could only have an enigmatic astrological chart. It helps to have it in sight when looking at his early life.

Off to A Fine Start

When young Dmitri was nine he began piano lessons with his mother who was a pianist, and at the age of thirteen he was enrolled in the St. Petersburg Conservatory. He soon demonstrated himself as a talented pianist and gifted at composition. He was eight when the First World War broke out and eleven at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution.

At the Conservatory during the Civil War with its many famines and other deprivations, he was well taken care of and rewarded his mentors with a composition that would become his First Symphony. Its first performance was in May 1926 when Shostakovich was only nineteen; the work brought him immediate national and international attention as a rising young star of his nation’s music. This was also a time when Stalin was consolidating his power and over the next few years would begin to take a dictator’s control of his country. Most people figured that Stalin’s repressive style would be temporary and they could wait it out for looser times ahead.

In the year after the First Symphony his decennials moved to Venus as general and specific planetary lord: although in detriment in Scorpio, Venus is with the Lot of Spirit in his Tenth House of Career. For a young person his rise was meteoric.

Composer at 25, already a national figure. Yes, Daniel Radcliffe of Harry Potter fame would have no trouble playing him in a movie.

In the next several years, coinciding with a progressed New Moon, Shostakovich wrote two more symphonies in conformity with the patriotic and revolutionary ideals of the young Soviet Union. He experimented with new international forms: living in Leningrad he lived within a strong cultural community and was exposed to much new music. His first opera, based on Golgol’s The Nose, got many good reviews but was criticized in some corners as a too modern. The regime was becoming increasingly repressive but if Shostakovich could give lip service to ideological orthodoxy we would be left alone.

In the early 1930’s he composed a jarring and thoroughly modern opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk based on a nineteenth century tale that reminds me a bit of Jason and Medea but involves lower-class characters. Shostakovich’s opera is naturalistic and frequently dissonant, at times angry and violent, overtly sexual in parts, and gripping.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_0VlQ8MLG0&list=RDQ_0VlQ8MLG0&t=98

Upon its opening in January 1934 Lady Macbeth was proclaimed a masterpiece, was performed frequently in Moscow, Leningrad and internationally. During this time Shostakovich had married and they were expecting their first child. All was good. Then, in January 1936, he received a phone call specifically asking him to attend a Moscow performance of his opera, for some very important people were to attend.

Traditional Natal Astrology – The Ascendant and its Ruler

Following my usual procedure of looking at a chart beginning with all matters of the Ascendant, we see Aquarius rising, no planets in the First House, and we go to Saturn (not Uranus) that governs Aquarius. Now things get complex.

Shostakovich was of normal stature, a bit thin and wiry, and was a chain-smoker. He displayed continuous nervous energy and his face was reputedly an assortment of grimaces and tics. One writer quoted in the Wikipedia article about him tells us of his character: “he is … frail, fragile, withdrawn, and infinitely direct pure child…[but he is also] hard, acid, extremely intelligent, strong perhaps, despotic and not altogether good natured (although cerebrally good-natured). He also had a strong network of close friends.”

His Saturn is in Pisces, in the mediocre second house but is heavily aspected. Saturn is in sect in his diurnal chart but is rather dim and contemplative in Pisces, perhaps tending toward resignation or depression. On at least two occasions he thought of suicide. He was socially awkward with people who were not friends and colleagues.

Saturn in Pisces is in a mutable sign. I look for the opposition from Mars, another mutable sign, for the composer’s fidgety nervous energy, a quality not lessened by his frequent fear after 1936 that the secret police could show up at any moment.

Mars in Virgo, in opposition to Saturn, tells us of dark drive that empowered his work and allowed him to keep producing under difficult conditions. The opposition from Mars helped channel Saturn’s darker spirits into creative fury, but, toward the end of his life, also toward bitter resentment.

Saturn in Pisces is governed by Jupiter (not Neptune) and his Jupiter in Cancer is in trine to Saturn. Jupiter is strong by being exalted Cancer but is in the Sixth House, a place disconnected by sign to the Ascendant. We can also look at both planets of the collective being in water signs that contribute emotional sensitivity and empathy. Jupiter is the planet of making connections with larger social realities than the personal. As a composer – but not as a personality – Shostakovich was self-expressive in a way that could express the condition of his society and an historical era.

Moon and Aspect Configuration

It’s hard not to notice Shostakovich’s Moon, in Capricorn and in the Twelfth House, also in aspect to his Ascendant ruler Saturn. Moon doesn’t particularly work well in Capricorn, tending toward dour responses and is more austere when a little self-indulgence would be better. In the Twelfth House, Moon wants to be left alone but must deal with many forces larger than his professional and personal life and (especially in Capricorn) may respond to that in a self-protective fashion that others might construe as cowardice.

The Moon’s sextile to Saturn brings more of the emotional qualities of Moon into the dark grey planet’s sphere. This may give an emotional and contemplative depth to his creative output.

Looking further, Moon’s application is a trine to Mars in Virgo, further disclosing Mars’ significance in his chart. In spite of his jittery nervous presence, Shostakovich had strong work habits and the ability to work quickly and in a concentrated manner. This is especially important as Mars is the ruler of his Tenth House of career. (For those interested in Virgo stereotypes, Shostakovich was almost pathologically clean in appearance and rigid in how he managed time.)

We can also look at the Moon’s opposition to Jupiter and we see a need to integrate the personal (Moon) with the extra-personal (Jupiter), and it was through the medium of his music that he accomplished this. The opposition may also hint to us that his public ideological pronouncements (Jupiter) contrasted what he told friends and intimates (Moon) – when he was not worried somebody might turn him in to Stalin’s secret police.

Don’t these planets Saturn, Mars, Jupiter, and Moon all form an aspect configuration, what’s called a mystic rectangle? This is a four-planet configuration with two trines and two sextiles and two oppositions between four planets. In my view, this configuration itself adds no information outside of what we have determined from how planets relate to the one under consideration – relating to an area of a person’s life. It’s better to look at a planet of significance, like the Moon intrinsically or Saturn as the First House ruler or Mars as the Tenth House ruler and see how the other planets influence this planet.

Sun, Mercury and Venus

Shostakovich had Sun in Libra in the ninth – this is the house “joy” of the Sun. Sun also gets some benefit from the square from Jupiter, yet Jupiter is cadent. Additionally, Sun is in “fall” in Libra. Mercury also in Libra, appears to be hanging out with the Sun and having not much of an identity of its own. (Later, using modern techniques, we’ll see that this isn’t the case at all.)

Venus, the planet of music among other things, is in the Tenth House of profession, governed by Mars in Virgo that we have discussed already. Venus is in Scorpio, a sign of detriment for Venus. This doesn’t make for a weak planet but one that’s confused: Venus in Scorpio can be overly intense or austere when Venus’ job is to have fun and enjoy the finer things of life. Shostakovich could compose free-flowing cheerful music when it suited him, yet it’s particularly helpful to have Venus in Scorpio if you’re going to depict musically Stalin’s Great Terrors or World War Two .

Venus is the only visible planet in an angular house or even a fortunate one like the Fifth or Eleventh. Venus is also aligned with the Lot of Fortune in Taurus in the Fourth and is with the Lot of Spirit, also in Scorpio in the Tenth. This is a lot of focus on Venus!

What Do Non-Wandering Stars Add, and How Do We Use Them?

One tradition for using fixed stars is to note zodiacal conjunctions, particularly if the stars are close to the ecliptic or within a zodiacal constellation. (Since they move only one degree in seventy-two years, the conjunctions better be close!) Shostakovich’s Venus is conjunct Zuben Eschamali, also called the North Scale or Northern Claw: it is the star of the northern scale of the constellation Libra. Authorities have considered this star the nature of Mars and Jupiter, more benefic than its southern neighbor, and may indicate social or cultural involvement – implying a social or cultural standard of measurement – which is surely the case with our composer regardless of his personal desires.

Venus also sets at the same time as another star, Pollux of the constellation Gemini, and this configuration is called a paranatella, a “co-rising”. One can use planets at any angle rising with stars at any angle, although my preference is planet and star at the same angle within the day of a person’s birth. Pollux also has the nature of Mars and Jupiter, more the boxer than Castor, its twin the runner. Pollux adds an ingredient of competitiveness and feistiness to Venus. Setting co-risings (being ironical) imply either life in middle age and later or within a foreign country.

Co-setting also are the Sun and Spica, another star in a zodiacal constellation: it is the sheaf of wheat in the constellation Virgo. Spica, as the star of the harvest season, carries significations of abundance and fertility, and is considered the second-most positive star used by astrologers. (Regulus is #1.)

Other co-risings involve other prominent stars. Saturn culminates – manifests in the prime of life – with Fomalhaut, one of the “royal stars” and is in the constellation of the southern fish. This star is often associated with culture and refinement that are fine qualities for a major classical composer.

Finally, there’s the combination of Jupiter co-culminating and co-anticulminating with Sirius, the “Scorcher” of the ancients. This brightest star that is associated with the “Dog Days” of summer tends to magnify the effects of any planet with which it comes into contact. Jupiter, as the planet of inclusion into larger realities, included Shostakovich into the life of his nation, the history of modern music, and the history of the world in the middle of the twentieth century –but it was not an easy ride!

Outer Planets and What They Add

So far, we have gained much without using Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto: what if we include them? Uranus is in Capricorn conjunct his Moon. Since Moon can signify physical dimensions of life, we can see Uranus contributing to his physical restlessness and can signify physical manifestations of anxiety. We can also note by their placement in the Twelfth House that any rebelliousness would not be public but private and nuanced.

Neptune is conjunct Jupiter, and here it amplifies Jupiter’s role as a planet of the social and cultural, perhaps with Neptune the ideals of a culture. Shostakovich considered himself a Russian patriot even when its leadership was murdering its own people; he may have taken refuge in the higher ideas of his nation as a means to tolerate the realities around him.

Episode One: Downfall and Re-education

Back to the opera performance in January 1936. The first was his sudden fall from official grace. In the audience were Joseph Stalin himself and several members of the Politboro. It’s unclear at what point in the performance they all walked out, and the immediate result was the composer’s very restless night.

A few days after this concert appearing in Pravda was an unsigned article entitled “Muddle Instead of Music” that excoriated Shostakovich and his opera for unyielding dissonance, noise, and for bourgeois “formalist” tendencies that were contrary to the nature of good uplifting music for the people. Immediately the composer descended from national treasure to “enemy of the people”; his music was no longer played and he lost his conservatory position, he took to carrying around with him a toiletry kit in case the secret police arrested him without warning. His difficulties turned out to be an early chapter of the “Great Terror” that would engulf his country for the next several years, that would bring show trials and summary executions and the gulags into history.

Here is his chart the day “Muddle Instead of Music” was published.

Note that Shostakovich was having a Saturn return – if it was only that simple. Joining transiting Saturn was transiting Mars in Pisces, making for both malefic in aspect to natal Saturn. (Saturn is the domicile lord of his Ascendant and the dispositor for his Sun, Mercury, and Moon – not an unimportant planet!). Not only was transiting Saturn and Mars upon his natal Saturn, but it was also at that time opposing his natal Mars in Virgo. We have two malefic planets transiting two malefic planets, and, to be a trigger, retrograde Mercury was conjunct his Ascendant — this was the kind of enlightening feedback he did not want. Additionally, Moon had entered Pisces, the sign of his natal Saturn, the day the article came out.

The eclipse of December 25, 1935, one month before the fateful performance and its reception, was at three degrees of Caprico rn, conjunct his Uranus and Moon. By progression in the previous year Sun had moved from Libra to Scorpio and the First Quarter Progressed Moon occurred in September 1935 when the Moon entered Aquarius. His solar return that year is downright ugly, with Saturn on the Ascendant opposed Venus in Virgo and both is square to Mars in Sagittarius. I guess Mars was Uncle Joe.

rn, conjunct his Uranus and Moon. By progression in the previous year Sun had moved from Libra to Scorpio and the First Quarter Progressed Moon occurred in September 1935 when the Moon entered Aquarius. His solar return that year is downright ugly, with Saturn on the Ascendant opposed Venus in Virgo and both is square to Mars in Sagittarius. I guess Mars was Uncle Joe.

Shostakovich survived: he publicly apologized and eked out a living writing film scores since other sources of income had dried up. He also saw many of his friends and colleagues being arrested and going to the gulag – but they never came for him. He continued working on a Fourth Symphony but withdrew it before its first performance – it would have been the end of him, under current circumstances. (It was not performed until 1961.)

He was given a chance to redeem himself by “responding to just criticism” in writing a Fifth Symphony and the rest is history. His Fifth Symphony was first performed for a select group of party officials and they thought it was fine, for the composer described it as a joyful and optimistic work. It premiered in November 1937 with a program note describing it as “a lengthy spiritual battle, crowned by victory.” It was a con job that worked but the audience wasn’t fooled.

Its first performance was enthusiastically received, its immediate popularity was such as to qualify as his effort at rehabilitation. Today it is his most frequently performed and recorded work. The question remains – is the work and especially its ending a message of heroism or of oppression? We can focus on the moving third movement or the piercing and noisy fourth whose opening one listener likened to “the iron tread of a monstrous power trampling man” and whose ending was depicted by another not as heroic but as being pummeled.

His rehabilitation had begun. Within a year he was back in favor, thanked their national leaders for helping him improve as a composer, and slowly began other compositions. He had finished a Sixth Symphony and had begun conceiving a Seventh.

Modern Astrology: Midpoint Combinations

We return to his natal chart and this time it’s to look at midpoints, a modern technique to match our modern composer.

In the middle (not muddle) is Venus: there’s Sun and Mercury conjunct on one side, Moon and Uranus on the other, both equidistant from Venus. Here’s an independent mind (Mercury/Uranus) and a nonconforming spirit (Sun/Uranus) and integrated attitude toward life (Sun/Moon) but only through his music (Venus).

Notice that between the oppositions of Moon and Jupiter and Mars and Saturn there’s also a midpoint: the lunar nodes! How do we consider the nodes? In the context of midpoints, the Lunar Nodes form an axis that relate to strong personal relationships to others, on a small scale or large scale. Let’s break down this natal combination.

With the nodes bringing them together, Moon-Saturn gives loneliness and mistrust; Mars-Jupiter is a patriot or crusader but Mars-Neptune makes for confused anger or idealistic warfare. Saturn-Uranus is also there, vacillating between cautious conformism and impertinent eccentricity. They were all true of him.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5YXwE6VTT6g

Episode Two: Great Patriotic Hero and Leningrad Symphony

During Stalin’s Great Terror another crisis was brewing elsewhere, as Hitler and the Nazis had become more aggressive and another European war was at hand. In August 1939 Hitler and Stalin signed a non-aggression pact and two weeks later Hitler invaded Poland to start World War Two and Stalin took his chunk of Poland as a secret part of that bargain. Then in June 1941 Hitler invaded Russia. On the heels of the Great Terror, Hitler had brought another catastrophe to the Soviet nation.

Just before the invasion Shostakovich had some interesting secondary progressions: Jupiter stationed retrograde and Mars moved from Virgo into Libra. Hitler will bring out the patriotic in him and, at least for a time, align him with a common sense of purpose.

The city of Leningrad (now again St. Petersburg) was cut off by the Germans for 900 days.

Continuing to live in Leningrad when the Germans invaded, Shostakovich was rejected in his request to join the army and eventually worked for the fire brigade for the Conservatory. He had begun working on a Seventh Symphony when the invasion occurred and that autumn told a radio audience that he had finished the first two movements of his upcoming Leningrad Symphony. As the siege began he was ordered to leave the city. He finished the piece far out of danger and it had a legendary voyage for its first performance abroad. In August,1942 the remaining musicians in Leningrad performed this piece as a statement of defiance and resoluteness. This event made Dmitri Shostakovich a national and international hero in the fight against the Germans. I’ll let Alex Ross tell it from The Rest is Noise (2007).

Transiting Sun was opposing his natal Ascendant and in square to his natal Venus.

We have yet again a configuration of transiting Mars and Saturn with natal Mars and Saturn. Now transiting Saturn is in square to the natal Mars-Saturn opposition and transiting Mars is coming to a conjunction with natal Mars – there is more emphasis on natal Mars here and less on natal Saturn. You may also notice that transiting Jupiter was completing its conjunction with natal Jupiter and Neptune and had previously aspected the other planets – like Sun and Moon – in cardinal signs. These were still difficult days for him but he had a cause and, became a national hero.

Later he would say very different things about this symphony. He had already begun the work when the invasion began and it wasn’t necessarily about resisting the fascists – it was about the fight against totalitarianism that included both Stalin and the Nazis. The Seventh Symphony is long, somewhat overwrought, and compelling. It worked marvelously as a propaganda piece for Stalin and the cause against the Germans regardless of its artistic intention.

You may also notice that transiting Neptune is at the last degrees of Virgo and is about to go into Libra and will conjunct his natal Sun by autumn of that year. Subsequently, as the war wound down, transiting Neptune will form aspects to his many other planets in the cardinal signs. This brought to light his Eighth Symphony, a dark and gloomy work that came out as the Soviet troops were moving toward victory.

Iconic cover when his Seventh Symphony was deemed part of the war effort against the Germans.

In 1938, the year after he dodged the bullet — literally — with his Fifth Symphony, his decennial changed to Moon-Moon, generally not a pleasant combination considering his natal Moon in the Twelfth House. During the Leningrad Symphony period, it changed to Moon-Saturn: the two planets are in sextile to each other, and Saturn, along with Venus, has the most prominence in his chart.

In 1943 he had a progressed Full Moon, at the height of his popularity as a national asset. His family moved to Moscow at that time.

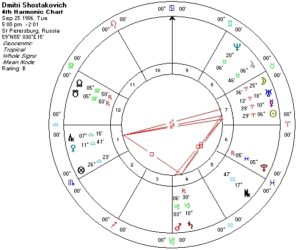

A Harmonic Interlude

Earlier I stated I would discuss Shostakovich’s Mercury placement further. A traditional analysis doesn’t give us a lot of information; adding midpoints does bring his independence and rebellious intellect into view. To see more we enter the murky roads of astrological harmonics.

The basic concept is to divide the circle we divide it into certain numbers. An opposition of 180 degrees is a Second Harmonic configuration, a square of 90 degrees is a Fourth Harmonic. Then we further divide and get Eighth Harmonic 45 and 135 degrees, the semi-square and sesqui-quadrate of a square and a half, respectively. Only one more division here: 22.5 degrees, and they are Sixteenth Harmonic configurations. (Orbs become progressively tighter.)

In Shostakovich’s chart, we notice that between Mercury at 02 Libra and Venus at 17 Scorpio there’s an orb of 45 degrees that place them in semi-square to each othe r. That’s nothing important but there’s another planet in harmonic configuration, Saturn. How? Using chunks of 22.5 degrees, Saturn at 113 degrees from Venus is 90 + 22.5 degrees, and Mercury is 158 degrees away, and opposition minus 22.5 degrees. This configuration becomes less obscure with a Fourth Harmonic chart where Mercury and Venus will appear in an opposition and both planets square Saturn.

r. That’s nothing important but there’s another planet in harmonic configuration, Saturn. How? Using chunks of 22.5 degrees, Saturn at 113 degrees from Venus is 90 + 22.5 degrees, and Mercury is 158 degrees away, and opposition minus 22.5 degrees. This configuration becomes less obscure with a Fourth Harmonic chart where Mercury and Venus will appear in an opposition and both planets square Saturn.

This allows us to see further the prominence of Saturn in the composer’s chart and in his life: the contact with Venus would limit him and channel his music into Saturnine territory. Mercury, less prominent in his chart, is another matter. On one hand, he was often reduced to making public proclamations – apologies, condemnations – that he did not believe. On the other hand, he became quite good at mimicking the lingo of his totalitarian authorities; Alex Ross states he was a fluent speaker of Soviet officialese, “with its ponderous jargon, empty clichés, and numbing repetition.” (p. 255) This was not the skill Shostakovich wanted to have but it would have to come in handy frequently.

The Remainder

Dmitri Shostakovich was only in his early thirties when the Leningrad Symphony gave him national and international fame. After World War Two he lived another thirty years that brought him many personal and professional ups and downs and a prodigious amount of composition.

Many thought that with victory against Hitler the Soviet Union, now a world power, would be a little lighter, but soon after the war ended another Great Terror began. This may have been partly caused by Stalin’s increased paranoia and this campaign contained a strongly anti-Jewish element. In February 1948 he and fellow composers (Prokofiev, for example) were officially reprimanded for their “formalistic” musical tendencies, their ignoring or careless indifference to the needs of the Soviet people. Prokofiev, who missed the first go-around because he had only recently returned to the Soviet Union, couldn’t physically tolerate the pressure; Shostakovich was less well-equipped than before but forged ahead and wro

When Shostakovich visited the United States in 1949 as part of a culture tour, anti-Communist demonstrations followed him.

te some of his best pieces, even if they, like his Fourth Symphony, would have to be played much later.

Again he lost university positions and his work wasn’t played. His teenage son was forced to denounce his work. Again the electricity was turned off in his apartment and most of his friends left him except his Jewish friends.

In 1949, on a personal request from Stalin who reinstated his works for the occasion, Shostakovich visited the United States. Although he was warmly welcomed by a musical community that valued his work, he was reduced to mouthing party propaganda and became in his own way a symbol of Soviet repression of the arts. This was during a Saturn-Saturn decennial: although he was treated like a celebrity the whole affair was painful for him from beginning to end.

In March 1953 Stalin died or was assassinated. Shostakovich responded that year by composing a Tenth Symphony that critics assert is a statement of survival over the conditions of Stalinism. It was also more “formalistic” that it was more modern and more demanding of its audience. Some consider it one of his best compositions. Just before its first performance, his decennials changed from Saturn-Mars to the more expressive Saturn-Sun. The following year progressed Saturn went direct and one would consider the burdens in his life becoming less. Unfortunately his wife died and, after some time he remarried and that marriage ended after three nightmarish years of a bad marriage.

The composer with Leonard Bernstein who helped bring his work into prominence in the United States.

In 1960, he reluctantly joined the Communist Party to take the position as chairman of a soviet composers’ union, an action he later said he took only under duress or in a moment of being drunk. This drove him into an emotional tailspin. He wrote his Eighth String Quartet thinking that would be his last work before he killed himself and it remains the most frequently played of his string quartets. It is not a cheerful piece but, like his Fifth Symphony, is very accessible.

Shostakovich lived on, married a third time in 1962 (far more happily than #2), and times rewarded him with a temporary but brief thaw at which time more dissident works – like Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich – could see the light of day. The composer responded to freer conditions with his Thirteenth Symphony that was a song cycle beginning with the Yevtushenko poem about the massacre of between 75,000 and 100,ooo Jews during World War Two at Babi Yar in the Ukraine. Because these was no longer Stalinist times Shostakovich was not arrested or were his works banned but the authorities did what they could to sabotage its performance and they succeeded.

For the next several years he continued to compose and as his physical health declined his work became more introspective and preoccupied with death. For a time, he could compose freely, but later things became tighter once again.

Shostakovich died in August 1975 of lung cancer at the age of sixty-nine. At that time, I was home for the summer and sometimes attended Boston Symphony Concerts at Tanglewood. I remember reading in the Berkshire Eagle that news of his death reached the BSO and its guest conductor Mstislav Rostropovich who with his wife were younger friends of Shostakovich, just before a performance of the latter’s Fifth Symphony.  The article contained a photo of a bouquet of flowers lying on the musical score for the Fifth Symphony. To that point I had heard of the composer and it would be many decades before I investigated his music. I recently found online the BSO’s documents for the evening and it’s riveting reading forty-plus years later.

The article contained a photo of a bouquet of flowers lying on the musical score for the Fifth Symphony. To that point I had heard of the composer and it would be many decades before I investigated his music. I recently found online the BSO’s documents for the evening and it’s riveting reading forty-plus years later.

Why Exemplary?

Why wasn’t Shostakovich a prominent dissident or moral guide like Andrei Sakharov or Alexander Solzhenitsyn? Why was he not for music what Albert Einstein was for science – eminent in his profession and, in general, a moral leader of his generation? The first answer is that these pretensions would have quickly earned him a one-way trip to the Soviet gulag, and that would have been the merciful alternative. The loss would have been his and ours.

During his lifetime, he was considered the great musical voice of his nation. He survived and managed to write wonderful music during an era that took its toll on millions, including many of his closest friends and companions. That he survived to become one of his century’s great composers was from a combination of his resourcefulness and determination and being lucky. Had he lived in less interesting times he may have written happier music but not left the legacy that helps us remember the era in which he lived. When currently in Russia the reputation of Joseph Stalin is undergoing a quiet rehabilitation, Shostakovich’s music stands as an enduring witness to totalitarian power and brutality.

I close with an assessment by David Farrington in the Grove Dictionary of Music: “Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass suffering of his fellow countrymen, and his personal ideals of humanitarianism and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical language of colossal emotional power.”