I Wish I Had Read This Article

What follows is an overview and timeline I wish I had when I first started reading the Divine Comedy. Many commentaries on the Divine Comedy give background historical information on this great poem, but usually in small and disconnected pieces as specific characters or events come up. Because the poem relates closely to its cultural, political, and spiritual background, it’s good to have the broad strokes.

Because the Divine Comedy is filled with notable people within the poet’s lifetime as well as historical characters, knowing who these people are will facilitate reading. When I first mention a character who also appears in the Divine Comedy, his or her name will be in bold. Since Between Fortune and Providence was written for an audience familiar with astrology, I have included important planetary cycles within my depiction of Dante’s era.

This is not an introduction to the poem itself, for there are plenty of those – including my own Between Fortune and Providence. Instead, this essay will enable you to read the poem with greater understanding.

Finger-Painting the Medieval Era

Had you lived in medieval Bologna this building would have dominated your town.

Religion: trying to understand the medieval Church takes a leap of the modern reader’s imagination. Christianity had a major role in helping make medieval Europe as civilized and refined as it was at its height. At the same time, the Church was often far more empire than religion and at times was unbelievably worldly. At other times, the church was vulnerable to being abducted by stronger secular rulers.

The papacy inaugurated some attempts to reform the Church. There were also reform movements from the monastic side; other Church reform movements, like the orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans, began with charismatic leaders. There were some failed attempts that have come down to us as “heresies.”

Politics: During Dante’s lifetime, the region we call Italy was comprised of many autonomous and economically diverse regions. In the south was the vulnerable but cosmopolitan kingdom of Sicily and Naples. The central region was governed by the Pope. In the wealthier and urbanized north, including Florence, there were many city-states frequently at war with each other and with the larger forces around them. During the medieval era, the “Holy Roman Empire” was but a loose confederation of warring princes and imperial control was only theoretical but occasionally attempted.

During the poet’s lifetime, the French monarchy became dominant in European affairs. Nostalgic for a renewed Roman Empire that was Christian, Dante did not know that the future would favor not empires but nations, not the Holy Roman Empire but France, England, and Spain.

This map of medieval trade routes shows the central position of Italy from the time of the Crusades for the next four hundred years.

Economics: the monetary and banking systems of Dante’s world would be more familiar to us. Unlike the more feudal Europe to its north and west, Northern Italy contained many commercial and banking institutions similar to ours. Italy benefited from its proximity to major trade routes and, with the Crusades, more traffic that moved back and forth across the Mediterranean. (Later these trade routes would help bankroll the Italian Renaissance.) As someone who was inspired by Francis of Assisi but lacked the saint’s generous temperament, Dante loathed the commercialization of Florence and Northern Italy in general.

Now we begin our chronology and we’ll start with an almost-mythic confrontation of Church and Empire.

Henry and Gregory

1077: The Investiture Conflict. Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV had been

Emperor Henry bows down to Pope Gregory. It would be only temporary.

excommunicated. In an attempt to be reconciled with the Church, Henry traveled over the Alps in the winter, put on the garb of a penitent, and waited barefoot in the snow for three days before Pope Gregory VII. The place of this famous encounter between Emperor and Pope was the castle in Canossa whose owner was Mathelda. Mathelda has the same name as the woman Dante places as forest deity of the Earthly Paradise and this has provoked divided commentary.

Although it looked very differently at the time, bowing to the Pope was a shrewd political move by Emperor Henry: as leader of the Church, the Pope had to “forgive” the Emperor. This gave Henry the time and opportunity he needed to augment his position in Germany. A few years later Henry came back to Italy with an army and Gregory was forced to flee and he soon died in exile from Rome.

Of interest to the astrologer would be this meeting in the Neptune-Pluto cycle: at this  time Neptune (in mid-Gemini) was in an opening square to Pluto (in mid-Pisces). More than any other planetary cycle, Neptune/Pluto is about the major turning points in a society and its culture.

time Neptune (in mid-Gemini) was in an opening square to Pluto (in mid-Pisces). More than any other planetary cycle, Neptune/Pluto is about the major turning points in a society and its culture.

This Neptune/Pluto cycle began in 905 at when European culture was beginning to settle down after the Viking invasions and there was renewed political and commercial activity, including the beginning of the feudalism system – but there was a long way to go toward stability. The first monastery at Cluny began at this time; this would be the center of the first of many reform movements in this era.

Before becoming Pope, Gregory was a senior advisor to Pope Leo IX who was attempting to reform the church by centralizing papal authority. (Another of Pope Leo’s chief advisors, from the monastic side, was Peter Damian who we meet in Paradise’s sphere of Saturn, Paradiso 21.) Leo and later Gregory aimed to (1) have popes elected by senior clergy, not appointed by an Emperor, (2) enforce priestly celibacy, (3) forbid the buying and selling of church offices, or “simony,” (see Inferno 19) and (4) turn over the power of appointing bishops (“investiture”) to the Church hierarchy, not to secular leaders, i.e. “lay investiture”.

When Pope Gregory sent an edict forbidding lay investiture, Henry appointed his own bishop in defiance. Gregory responded by excommunicating the Emperor (excluding him from the church and its sacraments) and proclaiming him deposed as secular ruler. If Henry didn’t repent within a year these two proclamations would be made permanent. So he walked to Canossa.

The investiture conflict continued past the lifetimes of both men and was formally resolved in 1122. The issue, however, was part of the much larger question of ultimate authority for Europe. Would the continent become a secular theocracy, whereby its temporal rulers also governed the church? Or was it to be a papal theocracy, whereby the pope was the universal leader and bestowed the church’s greater authority upon its secular rulers? The momentum went back and forth as neither side could prevail for long. By Dante’s time both Empire and Papacy had become seriously weakened, which resulted in political chaos and violence in Northern Italy. The result was that Europe never became a secular nor papal theocracy.

Crusades and Contacts with the Islamic World

Cacciaguida sent on a Crusade, killed by one from the religion, ascending to Heaven as a God’s part of the deal.

1091: Probable birth of Cacciaguida. This is the year reckoned for the birth of Dante’s ancestor. In the course of their long conversation in the middle cantos of the Paradiso, Cacciaguida relates his life, the life of the Florence of his era and its subsequent decline, and predicts the pilgrim’s exile. Cacciaguida tells of a Florence that was smaller, more homogenous, less commercial, and where the women dressed more decently. Although there is no independent record of this man Cacciaguida, there is no reason to doubt his existence.

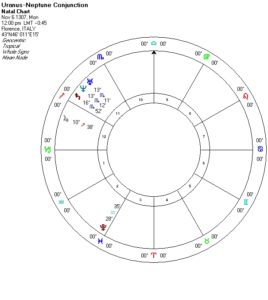

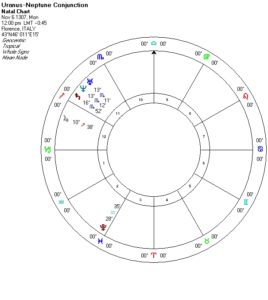

1092: First Crusade. We return to the larger world. In previous decades and far to the east of Italy, the Seljuk Turks had taken over many of the Muslim lands and had captured all of Asia Minor (our modern “Turkey”) from the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Emperor had appealed to Pope Gregory for help, but the Pope was too busy feuding with Henry IV. Times changed though, and in November 1095 Gregory’s successor Urban II called upon all Christians to “take up the cross” and recapture the holy lands from the Muslims. This also occurred as Uranus was approaching a closing square to Neptune, bringing about a change in religious and secular structure.

Two years later an expedition the “First Crusade” left for the east, passed through Constantinople and by 1099 had conquered and occupied significant land held by the Muslims. The victorious crusaders established Latin-speaking medieval states in the original Holy Land.

History has not been kind to the First Crusaders.

The Crusades brought great pillage and unnecessary slaughter. Future crusades were generally no more virtuous but were less militarily successful. In spite of the cavernous gap between ideal and reality, the activity of crusading as taking up the cross for God remained powerful in the European imagination from the medieval times up to the modern era. Dante was no exception to this; in the Divine Comedy the poet waxes nostalgic for the crusading ideal and, in his conversation with his ancestor, even casts himself as a crusader.

1138: Translations of Astrological Texts into Latin. During this time and in different parts of Europe, important astrological works from the Islamic areas were being translated. In this year Plato of Trivoli translated Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos into Latin, making the ancient writer of natural astrology available to the Latin West. Two years earlier Hugh of Santilla translated the Centriquium, falsely attributed to Ptolemy, which contained basic principles of applied astrology. Previously Adelard of Bath translated Arabic astronomical tables, works of Abu Masar from the Arabic, and constructed an astrolabe. The Jewish poet and astrologer Abraham Ibn Ezra, born late in the eleventh century, lived in Italy in middle of the 1100’s and wrote many of astrological works that have been recently translated into English.

1145: Second Crusade and Bernard of Clairvaux. In 1144 the Muslims recaptured the city of Edessa in present-day Iraq. Pope Eugenius III called for another expedition to the Holy Land to take back Edessa and to continue the conquest of the Holy Land for Christendom. The “Second Crusade” was an embarrassing failure.

One who enthusiastically promoted this new crusade was Bernard of Clairvaux. As the head of the Cistercian monastic order he was the model of the disciplined and contemplative life – and he was a writer, preacher, strong adversary, and one of the most respected religious people of his age. Bernard attributed the Second Crusade’s failure to the spiritual deficiencies of European Christendom.

Bernard was a staunch opponent of the new scholarly attraction for Aristotle and of the dialectical method that has come down to us as “scholasticism.” Instead, Bernard promoted personalized and experiential methods of religious practice and promoted the cult of the Virgin Mary. In the Divine Comedy Bernard appears at the very end of the poem, replacing Beatrice as the pilgrim’s guide to lead Dante to the Virgin Mary and the vision of God.

Along with many other kings and nobles, the Emperor Conrad III took part in the Second Crusade. One of his soldiers was the knighted Cacciaguida who died on the crusade. See Paradiso 15.139-148.

Pluto and Neptune were in opposition in the early 1150’s, when Western Europe saw a tremendous amount of political and religious activity: the second Crusade had failed, the fight between Emperor and Pope for Northern Italy was beginning, and a conflict between religious conservatism and the new styles of philosophy had begun. (The third quarter square occurred in the early 1320’s soon after Dante’s death.)

Pluto and Neptune were in opposition in the early 1150’s, when Western Europe saw a tremendous amount of political and religious activity: the second Crusade had failed, the fight between Emperor and Pope for Northern Italy was beginning, and a conflict between religious conservatism and the new styles of philosophy had begun. (The third quarter square occurred in the early 1320’s soon after Dante’s death.)

Italy and Empire

1156: Emperor Frederick Barbarossa stirs up trouble. In this year there was an

Emperor Frederick of the Red Beard. A now-discarded symbol of German national pride.

important meeting between Pope (Adrian IV) and Emperor (Frederick I). Frederick, far stronger than his predecessors, had come to Italy with his army, subdued a popular revolt that had exiled the Pope from Rome, and insisted that the Pope give him the crown. Reluctantly and after a short impasse, Adrian crowned him Holy Roman Emperor. In Germany there had been much conflict between Frederick’s family and the rival Welfs; the Emperor’s first order of business was to bring some amity between rival factions. Being crowned by the Pope was certainly one way of doing this.

Relative calm in Germany and legitimization by the Pope helped Emperor Frederick onto his next goal – to appropriate northern Italy. During the time of the Crusades the urban centers of Italy had become more prosperous, and they were theoretically part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Frederick’s dreams of greater empire ran into strong but uneven opposition. Pope Adrian and his successors were rather displeased with Frederick’s claims and the independent cities resisted him. The red bearded Emperor invaded Northern Italy six times but never established a permanent foothold there. At times he would dominate the region but then chaos in the German states would bring him back home.

Some regions in Italy allied with Frederick, others with his German opponents. (Florence, closer geographically to the Papal States, generally supported the Pope and stayed out of the fray.) After Frederick captured and burnt Milan to the ground in 1162, many of the nearby city-states formed the Lombard League, eventually routed Frederick’s troops in battle, and the two sides settled in 1183. Although officially part of the “Holy Roman Empire”, the Italian cities retained considerable independence.

Frederick then set his sights upon the Norman kingdom of Sicily and, to begin a claim to that throne, married off his son to the niece of the Sicily’s ruler. On his way to a Third Crusade, he died suddenly by drowning in 1190.

These events helped set the stage for the Italian politics of the thirteenth century that Dante was born into and that constitutes much of the Divine Comedy’s background. Supporters of the House of Welf became Italy’s “Guelfs” who would usually take the Pope’s side in a dispute; followers of the Hohenstaufen family became the “Ghibellines”, named after a Hohenstaufen castle named Waibingen. (You try to find an Italian equivalent to “Hohenstaufen.”)

1181: Heresies threaten the religious status quo. In this year Pope Alexander III designated two religious groups to be heretical. One was called the Waldensians, named after its founder Peter Waldo. This charismatic preacher, who had once been a merchant, gave away his possessions and preached poverty, the superiority of the simpler apostolic life, and individual study of the Bible. The other movement was even more dangerous to the religious status quo. Slowly emigrating from the East were the Cathars who, when they began to dominate southern France, were known as Albigensians. They promoted a view that the world of matter was in the realm of Satan and therefore the Christian incarnation was impossible. They also promoted a class of saintly people called the perfecti. This was not a Christian reform movement but an entirely new religion. Aided by indifferent or sympathetic local lords these groups began to attract many followers and grew to dominate the spiritual life of southern France and parts of northern Italy.

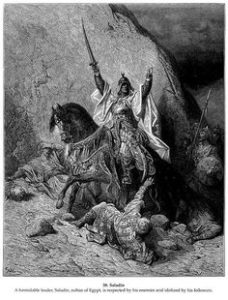

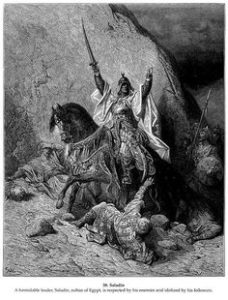

1187: A Virtuous Pagan Takes Back Jerusalem. In this year Saladin and his force of Muslim troops recaptured Jerusalem and nearby Crusader States from their Christian occupiers. Although a non-Christian, Saladin was considered virtuous by his Christian contemporaries. (Unlike the Christians in the eleventh century he spared Jerusalem’s inhabitants when he captured the city.) We see Saladin in Dante’s first circle of Hell that is reserved for the virtuous pagans. The poet’s words require no translation: “e solo, in parte, vide ‘l Saladino.” (Inferno 4.129) The result of Saladin’s success was another invasion from the west that history calls the “Third Crusade.” This was the campaign that claimed the life of Frederick Barbarossa who accidently drowned. The Third Crusade ended in 1192 with a truce between Saladin and Richard “The Lionhearted” and there would be no further re-conquest of the Holy Lands

1187: A Virtuous Pagan Takes Back Jerusalem. In this year Saladin and his force of Muslim troops recaptured Jerusalem and nearby Crusader States from their Christian occupiers. Although a non-Christian, Saladin was considered virtuous by his Christian contemporaries. (Unlike the Christians in the eleventh century he spared Jerusalem’s inhabitants when he captured the city.) We see Saladin in Dante’s first circle of Hell that is reserved for the virtuous pagans. The poet’s words require no translation: “e solo, in parte, vide ‘l Saladino.” (Inferno 4.129) The result of Saladin’s success was another invasion from the west that history calls the “Third Crusade.” This was the campaign that claimed the life of Frederick Barbarossa who accidently drowned. The Third Crusade ended in 1192 with a truce between Saladin and Richard “The Lionhearted” and there would be no further re-conquest of the Holy Lands

1194: Empress Constance and Frederick. Frederic Barbarossa’s son Henry VI invaded and appropriated the Kingdom of Sicily that included southern Italy. Henry had a claim on the throne, having been married to Constance who was the daughter of the kingdom’s last heir. Henry was also the Holy Roman Emperor and therefore had claim to Germany, but his interests were eastward toward Constantinople and the Holy Lands.

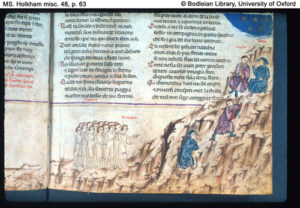

Henry unexpectedly died in 1197, leaving the widow Constance and a son three years old as the heir to the throne. Constance had

From a a fourteenth century manuscript. Hohenstaufen emperors were routinely excommunicated by the various Popes. In Purgatorio 3 Mandred leads a group of excommunicated people very slowly toward the healing torments of Purgatory’s mountain.

the good sense to name Pope Innocent III as the young boy’s guardian who proclaimed the toddler King of Sicily. We hear of Constance twice in the Divine Comedy. Manfred introduces himself in Purgatorio 3 not as the son of his father but the grandson of “Constanze imperadrice”, “Empress Constance”. In Paradiso 3, in the sphere of the Moon, Constanza is next to Piccarda who speaks of her as also having been taken from cloistered life and forced to marry for political reasons.

Innocent III would have been a natural ally of Sicily’s rival, the Welf-allied Otto IV in Germany. The Pope did crown him Emperor but soon became disillusioned of him and instead backed the young Frederick instead. Pope Innocent was hoping to take advantage of the young heir’s minority even if that meant the Pope backing a Hohenstaufen. This strategy would backfire, and Frederick would become the Papacy’s affliction for decades.

We now enter the equally strange world of the thirteenth century.

Intellectual and Religious Revivals

1200: Intellectual Revival. This year conventionally marks the beginning of the

University education back when. One inaccuracy is that it’s unlikely students would have had writing instruments or anything to write on.

university system. The university system became a fertile ground for the transmission of the works of Aristotle and others to the medieval culture, which became the basis for the intellectual renaissance of the thirteenth century. Accompanying the writings of “the Philosopher” were also the commentaries by the Islamic Averroes. These new teachings were exciting and feared and there was great conflict for decades over them. The epicenter for this conflict was the university at Paris.

What better time to begin an intellectual revival than a Uranus-Pluto conjunction?

During the time of the Uranus-Pluto conjunction the Catholic Church was controlled by its most powerful Pope, Innocent III. During a time of relative economic prosperity, there were also great challenges to church orthodoxy. The Cathars or Albigensians were at their peak in Southern France; in the universities, occasional bans on the teachings from the pagan philosopher and Islamic commentators were usually ignored by university professors and their students.

1208: Dominic and the Albigensians. Innocent III, having been unable to restrain the advance of the Albigensians, called a crusade against them. By now the French monarchy was available to support a crusade, and they had an eye toward eventually expanding their realm into southern France to the Mediterranean.

Innocent III had tried to convert Albigensians back to Christianity more peacefully. A few years earlier, arriving from the Spanish peninsula, Dominic de Guzman and his bishop asked the Pope’s permission to preach to the non-Christians in the East. Seeing a greater threat closer to home and clearly impressed by Dominic’s abilities, the Pope instead sent them to Southern France to preach to the Albigensians.

Dominic, a brilliant and fierce defender of his contemporary church, encountered many

Dominic receiving the rosary from Mary herself. Legends settled easily around both Dominic and Francis.

difficulties in Southern France. The Church’s previous missions to France mostly communicated the Church’s ostentatious wealth. Additionally, the Albigensian perfecti were generally quite learned and could be countered only by those skillful in dialectic. Dominic presented himself as a true man of God who was intelligent and adept at disputation. Several years later his ministry grew into the international “Dominican Order. During the 1200’s Dominicans would controversially dominate the universities in Europe.

In Paradiso 9 42-111, in the sphere of Venus, we hear from man who calls himself Folco. In 1205 he became the bishop of Toulouse, the major city in southern France and an Albigensian stronghold. Folco was a major player in the Albigensian crusades. In Paradiso 9 Folco discusses his previously changed life from troubadour to person of God, but not his subsequent actions against the Albigensians. His presence in the Paradiso speaks much of Dante’s bias in that conflict

Things would not turn out well for the Albigensians or the autonomous kingdoms of

The whole-scale genocide of the Albegensians was not a great moment in Catholic Church history.

southern France. As the crusading invaders captured more cities the region became involved in warfare between the various rulers and sovereigns. After many years and much loss of life, southern France became firmly under the control of the French king, many Dominican friars became inquisitors working to ferret out heretics, and the Albigensian religion was annihilated.

1210: Francis of Assisi. In this year the charismatic wanderer went to Innocent III, requesting that that he and his followers be given official permission to preach and to become an officially sanctioned order. Francis and his followers received an audience with the Pope (a miracle in itself), who gave his blessings to what would be called the “Franciscan Order.” Perhaps the Pope was taken by the barefoot preacher’s saintly presence, but likely this was a pragmatic move by Pope Innocent. Francis would begin a movement that could help inspire alternatives to the worldliness and wealth of the current Church. Innocent’s “big tent” approach, to find avenues for the truly religious but also leave Church institutions unchanged, helped give the Church an additional three hundred years of being “catholic” or universal. Francis was one of the great and influential personalities of his age. For Dante, he was a strong influence, a spiritual troubadour who wrote poetry, a contemplative who also preached to the Sultan.

Giotto’s depiction of Francis of Assisi handing his clothes over to his father go begin his life as a religious wanderer. The rest is history.

For Dante, Francis and his order is the perfect complement to Dominic and the Dominicans. Both men and their orders are presented in Paradiso 11 and 12. Those of both orders were to take a vow of poverty, yet their approaches were different: the Dominicans favoring a scholarly and dialectical approach, the Franciscans one that is more intuitive and emotional.

The Secular World of the Early 1200’s

1215: Beginning a Blood Feud in Florence. In this year a man named Buondelmonte de’ Buondelmonti was betrothed to the daughter of one family but left her suddenly and instead married the daughter of Gualdrada Donati (a family name we will encounter again). A member of the aggrieved Amidei family that was allied with the Uberti family (another family name we will encounter again), murdered Buondelmonti on a bridge near an old statue of Mars. This began a feud in Florence that would last generations and would increase the enmity of the Guelf/Ghibelline conflict. Cacciaguida discusses this incident in Paradiso 16.142-147.

1220–1250: The Era of Frederick II. After consolidating his gains in Sicily and

Frederick the Second and an eagle. It should have been a falcon, since in his abundant spare time he wrote a famous book on falconry.

buying off the nobles in Germany with large concessions, Frederick II was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome by Pope Innocent’s successor Honorius III. Frederick gained favor with the new Pope by promising to go on a crusade about which he then dithered for years. He also promised the Pope he would not attempt to unite Sicily and Naples with the Empire to the north and didn’t keep that promise either. The net result was that Emperor and Pope, this one and his successors, would be adversaries for the next three decades.

Advising the Emperor was Michael Scot, who, according to Inferno 20, had skinny flanks and practiced “magic fraud”. Being born in 1175 he was an older man to the young Emperor and was the Emperor’s personal astrologer. Previously he had translated Aristotle into Latin and became steeped in the major philosophical trends of his day, wrote an introductory book on astrology, and practiced different forms of sympathetic magic.

After years of stalling and then becoming excommunicated, Frederick II finally arrived in the Holy Land. In a move that angered both Christians and Muslims, he made a diplomatic deal with the Muslim leader of Jerusalem, the result of which was that Christians could again occupy Jerusalem and surrounding areas for ten years. On his return to Italy in 1230, he made clear his intention to unite his Kingdom of Sicily and the city-states of northern Italy — and the Papal States in between. For the next twenty years, occasionally interrupted by peace treaties, Frederick’s dream of a larger empire was opposed by both the papacy and the northern cities.

Like those of his grandfather, this Frederick’s plans to conquer and control Italy were never realized. One difficulty was that he encountered a series of strong popes who did what they could to thwart him. In addition to the use of military power and material aid to Frederick’s enemies, the popes repeatedly excommunicated the Emperor, making it more difficult for him to exert authority. In Inferno 13, the area for those who killed themselves, we meet Piero delle Vigne, one of Frederick’s trusted counselors, and a learned and literary man on his own. Piero suffered a reversal of

In Inferno 13 Piero della Vigne, as a suicide, is reduced to an eloquent if self-pitying thorn bush.

of fortune in the late 1240’s when he fell out of grace with Frederick. The once-favored prime minister was jailed, blinded, and eventually killed himself. We find delle Vigne unforgettably portrayed in Inferno 13 as an elegantly speaking gnarled bush.

Frederick was far more Italian than German, was multilingual (including Arabic), was tolerant of Islam and stocked his armies with Saracen mercenaries, discoursed in philosophy, wrote his own poetry, and was a thoroughgoing religious skeptic. He made Sicily a place of culture and refinement and, critical to Dante’s poetic lineage, helped introduce the troubadour tradition of poetry from Provence to Sicily, from where it would later move to central Italy. Frederick well earned the appellation Stupor Mundi that sounds much better in translation: “Wonder of the World”.

After conducting decades of civil war in Italy, after some victories but many defeats, Frederick II died of dysentery in 1250. After his death Italy would continue fragmented and often at war with itself. The Holy Roman Empire became a polyglot of German principalities and Dante would resent the Emperors’ consequent neglect of Italy.

Where does one find Frederick in Dante’s afterlife? Dante mentions him only in passing: he is in Inferno X in the place assigned to heretics. In the poet’s view Frederick would have been the kind of ruler who could have brought order to Italy, and indeed Frederick’s dream of a united Italy as the center of the Empire was also Dante’s dream. However, Frederick, in Dante’s eyes, was more religious skeptic (or even pagan) than Christian, nor could he have been considered just or temperate. In Purgatory and Paradise we find many rulers but it seems that the shadow of Frederick II hovers over all of them.

1252: Alfonse the Wise and his projects. Here was another important year for the dissemination of astrology in the West. Alphonse the Wise, king of Castille, had an abiding interest in astronomy and astrology. He commissioned the “Alphonsine Tables” from an international group of scholars. These updated the Toledan Tables from the second half of the eleventh century and were in use for several centuries afterwards. Alphonse also commissioned a translation of the Picatrix that became the basic text for magic in the medieval era and the Renaissance.

1254: Manfred Inherits the Hohenstaufen Dynasty. Conrad IV, who had been King of Germany, succeeded Frederick and Pope Innocent IV preached another crusade, now against Frederick’s son. The young emperor died in 1254 and was succeeded by his half-brother, Frederick’s illegitimate son Manfred. The focus of activity was south Italy and Sicily, leaving the central and northern city-states to fend for themselves and feud with each other.

More Theological Developments

1257: The Four Schoolpeople of Paris. At the university in Paris doctorates were awarded to two renowned teachers: Bonaventure the Franciscan and Thomas of Aquinas the Dominican. Both men were Italians who, after ordination, had traveled to Paris to study philosophy and theology. When Thomas arrived Bonaventure had been in Paris one year studying with a Franciscan. Thomas and Bonaventure surely knew each other but they were far apart temperamentally and on some basic theological issues. It’s possible that at the ceremony there was also a young student attending who later became

In Paradiso 10 they’re all set with each other in harmony. That was not in their lifetimes.

influential and controversial: Siger of Brabant.

Bonaventure later would become the head of the entire Franciscan order and is credited with compiling the definitive biography of Francis of Assisi. His theology stressed the role of faith, intuition and the good will to provide means necessary from our side for salvation (God’s grace is the other side). Although well-schooled in the philosophical trends of his time, Bonaventure had little use for many of the speculations of his colleagues and considered philosophy the “handmaiden of theology”. Among many he is considered the second founder of the Franciscan order.

Thomas was from southern Italy and his family was related to Frederick II and the

The Triumph of St. Thomas, a fourteenth-century work in the (Dominican) Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

Hohenstaufens. As a young man he felt the call for the priesthood and only after outlasting great family resistance (including locking him up) did he become a Dominican at the age of 19. One year later Thomas went to Paris and met Albertus Magnus there. He later followed his teacher to Cologne and spent eight years at the papal court, but twice more returned to Paris to teach and write. During Thomas’ third stay in Paris, beginning in 1268, he wrote the monumental Summa Theologica.

Thomas endeavored to take the intellectual fight to Siger of Brabant, the best known of the “Latin Averroists,” named after the great Arabic commentator from the previous century. This group took its Aristotle to heart and endeavored to pursue a purely rational philosophy without attempting to reconcile it with Christian teachings. Siger promoted the idea of “two truths” whereby conflicting conclusions of philosophy and theology could both be valid within their own spheres.

Thomas of Aquinas would have none of this. There are truths of our worlds that can be discovered by empirical investigation and philosophical dialectic, and further by Christian revelation, but only one truth. The grand plan for The Divine Comedy, with its widening ranges of truth as it proceeds through the regions of the afterlife, follows Thomas’ presentation. There was also a strong political influence. Unlike the Augustinian tradition that regarded the “City of Man” as subordinate to the “City of God” (the Church), Aquinas and others argued that the political life has its own place to support the development of virtue and to provide a supportive environment for the work of human salvation. Dante’s political theory presented in The Divine Comedy is close to this view.

In Dante’s Paradise we see all four schoolpeople of Paris – Thomas, Bonaventure, Siger, and Albertus Magnus — together as glittering lights among the circular garlands of stars that comprise the Sphere of the Sun (See Paradiso 10-13). Their difficulties with each other in life served to promote a greater good.

Guelfs and Ghibilines in Florence and Beyond

Farinata, discoursing from his fiery grave in Inferno 10.

1260: Florence Goes Back and Forth. Although Florence was considered a Guelf city there was an important interruption. In the battle of Monteperti near Siena, an alliance of Ghibellines led by Farinata degli Uberti routed the Florentine Guelfs. Another participant in this battle was Bocca delgi Abati, a Ghibelline leader who pretended to defect to the other side and helped turn the battle against the Guelfs. In Inferno 32 he is stuck in ice with only his head above the surface. When Dante finds out who he is, he kicks him in the head.

After this battle the Ghibellines and their allies took over the city of Florence. In a council of the victors, Farinata stood against Florence’s destruction and the city survived. Faranata had been the head of the Ghibellines in Florence for decades previously, was exiled with his fellows in 1248 but returned three years later. Cast as a haughty aristocrat speaking grandly from a flaming tomb, Farinata is one of the more interesting characters of the entire poem. See Inferno 10.

A hypothetical representation of Guido Bonatti from the 1700’s

During this time Guido Bonatti was the celebrity astrologer to various Ghibellene leaders. At one time Bonatti worked for the governor of Padua, Ezzelino da Romana, known for his cruelty. Ezzelino appears in Inferno 12 cast into a river of blood. Bonatti also worked for Count Novello who was the Ghibellene leader of Florence after the battle of Montaperti. The great astrologer also worked for Guido da Montefeltro, a military and political leader who the poet assigned to the place in Hell for evil counselors (Inferno 27).

Bonatti’s monumental Liber Astronomiae or “Book of Astronomy” was one of Dante’s sources and remains a primary text for medieval astrological doctrine. By his lifetime many astrological works had been translated from the Arabic and he had a complete tradition to rely upon for his work. Containing detailed instructions on horary, natal, and predictive astrology, Bonatti’s text is one of history’s great works of practical astrology.

1265: Dante’s birth. In this year the future poet was born to a notary father and a mother from family of minor nobility. He had one sister. Dante’s mother died when he was a child and his father died when he was a teenager.

1266: The Hohenstaufen Dynasty Ends; Sicily goes French. Manfred the son of Frederick II was killed in battle at Benevuto. Pope Clement IV had previously excommunicated Manfred and formed an alliance with Charles of Anjou (brother of Louis IX the king of France); Charles sent a force against Manfred who was betrayed by his own barons and was killed. Manfred makes a dramatic appearance in Purgatorio 3 still showing the wounds of this battle.

Charles of Anjou took over areas in southern Italy held by the Hohenstaufen but formed an alliance with Venice and aimed his intentions east. Sicily would stay in French hands until 1272, when the Sicilians overthrew and massacred the French in the “Sicilian Vespers.” Don’t think this was the beginning of independence for Sicily: for decades the island would be contested between different outside forces and eventually be governed by the Spanish until the 1800’s.

1266: Peaceful Florence. The Guelfs took back Florence for good, which ended the Ghibellene presence in the city. Farinata’s family was exiled once again. Dante would grow up in a relatively peaceful Florence. Later the political situation in Florence would once again become deadly as the Guelfs themselves split into factions.

Dante Alighieri Steps Onstage

1274: Life-Changing Events. At the age of nine the lad Dante first saw Beatrice and  fell in love with her on the spot. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure both die.

fell in love with her on the spot. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure both die.

1283: Dante’s Early Life. In this year the teenage Dante was married to Gemma Donati whose ancestors we have met and whose relatives we will meet soon enough. Dante and Gemma had four children and appeared to have had a relatively happy marriage, interrupted by his exile. Beatrice herself was married in 1287 to a man from a family with similar wealth and social standing as hers. Dante mentions neither marriage in his poetic writings.

During his early adult years Dante may have spent time in University of Bologna — where he may have learned his astrology. In Florence one of his teachers was Brunetto Latini, from whom Dante learned classical literature and to read Virgil. Latini was also an example of a politically involved literary person as Dante himself would become. We meet Latini memorably in Inferno 15.

The Alighieri family had property outside of Florence, some of which was rental property, and managing this property was a source of income for Dante and his family at this time.

1289: Florence Victorious. Dante participates in the battle of Campaldino, where Florence and allies defeat neighboring Arezzo and their Ghibellene allies. In Purgatorio 5 we meet the Ghibelline leader Buonconte da Montefeltro (son of Guido who is in hell), who like Manfred was a late penitent. This battle’s outcome insured that Florence would dominate Tuscany.

1290: Beatrice dies.

1291: End of the Crusader Era. We take one last look at the Holy Lands. After laying siege to the city, the Muslims captured the city of Acre, the last of the Crusader States, thus effectively ending the era of the Crusades. The Divine Comedy, particularly the Paradiso, waxes nostalgic for the bygone times of the crusades.

A nineteenth-century painting of Dante meeting Beatrice by accident.

1293-1294: Dante the Poet. During this time Dante composed the Vita Nuova, (“New Life”) containing sonnets and commentary that told of his love for Beatrice and gives a narrative of his own poetic and spiritual growth. The Vita Nuova, along with Dante’s other early poetry, helped establish him as an important poet in Florence. During this period, he experimented with different contents and poetic styles that would serve him well later.

The content of Dante’s poetry stemmed in part from the poetic troubadour tradition that began in Provençal France, moved from Sicily (thank Frederick II) and then to the city-states in central and northern Italy in the years before Dante’s birth. Over time this tradition changed from a focus on love and affairs of the heart to include a more spiritual dimension whereby personal love brings the lover closer to God.

In Purgatorio 26 we meet Guido Guinizzelli, a poet from Bologna in the previous generation, to whom Dante feels indebted. Guinizzelli, however, defers to the Provencal poet Arnaut Daniel from earlier in the century. As befitting fashioners of love poetry, they are purifying lust. Fifteen years older than Dante, Guido Calvacanti was the best-known poet in Florence when Dante arrived on the scene and was somewhat a mentor to the younger poet although their work differed greatly. (Calvacanti was still alive in the spring off 1300 and therefore doesn’t appear in the Divine Comedy, although his father does.)

1294: Dante’s Important Friend. Charles Martel was the grandson of Charles of Anjou and son of the king of Sicily, heir to many kingdoms, and briefly stayed in Florence on his way to Naples. In Paradiso 8 Dante and Charles Martel converse as old friends reuniting. Martel also may have inspired Dante to enter political life.

1294: Boniface VIII becomes Pope. He replaced Celestine V who he had talked

The overbearing but rather tragic Pope Boniface VIII. He wanted to be an imperial pope but he was born a hundred years too late, or two hundred years too early.

into abdicating.

Celestine had considered himself more a contemplative than a public person. When called to public life he preferred his private life. Celestine’s “Great Refusal” (see Inferno 3) was a refusal of the call to becoming active in the world.

Even contemporary historians view the new Pope Boniface VIII as overbearing, vain, and ambitious. This is fairly charitable assessment compared to Dante’s treatment of him.

1295: Dante becomes a politician. At this time the poet enters a period of active participation in the affairs of Florence. To qualify for holding office, he became a member of Guild of Physicians and Apothecaries (he was neither). Dante was quite successful as a man of influence, becoming known as a very persuasive speaker with strong convictions.

April 1300: the probable time of The Divine Comedy’s narrative.

Spring-Summer 1300: Setting up Dante’s downfall. Dante’s political ambitions culminated in his becoming one of the six priors for Florence. By this time Florence’s ruling Guelfs had split into “black” and “white” factions and a family struggle between the Cerchis and Donatis and their respective allies. Dante belonged to the whites, who were more willing to oppose the pope and church establishment than their opponents. Beginning at a May Day dance, Florence had broken into violence between the two factions. To restore order the six new priors, including Dante, banished the leaders of both sides, including Guido Calvacanti from the whites and Corso Donati from the blacks. Calvacanti was returning to Florence but died of malaria at the end of the summer; Donati’s exile continued. Donati appealed to Pope Boniface who asked the French nobleman Charles of Valois (brother of King Phillip IV of France) to become Florence’s “peacemaker”. This created an unholy alliance between a greedy Pope (Boniface), an ambitious French nobleman (Charles), and a ruthless Florentine political leader (Corso Donati) and an evil brew for our poet turned politician.

June 19, 1301: “Nihil fiat.” Through his cardinal as emissary, Pope Boniface asked for military support from Florence for an excursion into southern Tuscany. The white Guelfs opposed this proposal and on this date Dante gave his famous Nihil fiat speech (“that nothing be done”). This only increased tensions between the Florentine whites and the Pope.

November 1, 1301: The Black Guelfs take Florence. At the instigation of (and with payment by) Pope Boniface, Charles of Valois entered Florence with his army and occupied it. Although he had promised a peaceful occupation, he let Corso Donati and other exiled black Guelfs back into the city, and within a week they had complete control. Donati and his allies began a bloody purge of their adversaries while the French looked the other way.

Dante was elsewhere at the time of the takeover. He may have been on a prior mission to the Pope to attempt an agreement with him, and he may have been detained there when Charles and the Black Guelfs occupied Florence. Had Dante been in Florence he could easily have been killed.

Life in Exile

January 27, 1302: Dante’s Exile Begins. The Black Guelfs controlling Florence condemned Dante and others of the white faction on trumped-up charges of financial mismanagement and for defying the pope and were sentenced to banishment. On March 10 Dante was sentenced to death if he attempted to return to the city. Dante never returned to Florence.

Once Dante had accepted the reality of his exile he continued studying and writing and gradually built up to the Divine Comedy. He continued to write poetry, of course. He wrote but did not complete De Vulgari Eloquentia about the evolution of language and the Convivio that contained philosophical speculations that would later appear (and sometimes to be refuted) in the Divine Comedy. De Monarchia, which contains his political theory, was written during his last years. Many of Dante’s letters also survive.

In Paradiso 17, Cacciaguida tells Dante about his life as an exile. Dante would try to get

On the sphere of Mars Dante’s ancestor Cacciguida fortells to Dante his coming exile and wandering.

back into Florence by allying himself with other white Guelfs but they turn out to be the wrong people and their enterprise will fail. This would leave Dante, Cacciaguida says, “a party for yourself.” The poet continued to be involved in politics, not as an office holder but as a partisan and writer of polemics and occasionally as a diplomat. In exile he was generally hosted well, yet, says Cacciaguida, to an exile the host’s stairs always feel heavier and the bread tastes saltier.

September 1303: Pope vs. French King. The papacy of Boniface VIII did not end happily. The French King Philip IV was as tough a political fighter as Boniface and the two feuded over the issue of taxing the French clergy. Eventually they made a truce but Phillip emerged with the advantage. In this month troops led by a representative of Phillip went to a papal residence at Anagni. Some of them assaulted and imprisoned Boniface, and the Pope, although freed quickly, died shortly afterwards.

Dante was horrified by this incident. Although he detested this Pope, he likened Phillip’s part to Pilate letting Christ be attacked. (See Purgatorio 20.85-90.) The next Pope, Benedict XI, died shortly after taking office. His successor Clement V was a puppet of the French monarchy. The papacy itself moved to Avignon in 1309 where the French would call the shots for the next several decades.

The year of the Uranus-Neptune conjunction was not momentous in the history of

Dante began the Inferno while continuing to hope to return to Florence. As the Divine Comedy progressed his hopes dwindled and his anti-Florence rhetoric became more vehement.

Northern Italy, although in less than two years the Papacy would move to France. Probably in the following year Dante began The Divine Comedy.

1310: Florence threatened. The Black Guelfs ruled Florence in the early 1300’s but

they faced many crises, particularly in the next decade from an outside invader. Although the Holy Roman Empire had become weak and divided since the times of Frederick II and Manfred, a new Emperor Henry of VII was intent upon uniting Northern Italy under imperial rule. By 1310 Dante was writing letters to the people of Florence telling them to surrender to a legitimate monarch and a great person. The Florentines thought differently: backed by outside forces concerned about the balance of power, the city put up a tough resistance and repelled Henry who died the next year. Backing Henry cast Dante as a traitor to his own city and any hope for his return from exile died. In Paradiso 30.133-141, the pilgrim sees the seat in high Heaven that Henry will someday inhabit.

1308-1321: Divine Comedy and aftermath. Dante began the Inferno. In 1312 Dante

Henry the VII, who wanted to be like Charlemagne, instead was one more Emperor who couldn’t capture Italy.

moved to Verona where he lived well as guest of its ruler Can Grande della Scala. During his stay in Verona he finished much of The Divine Comedy and he dedicated the Paradiso to its ruler, possibly in attempt to curry additional favor from him. At least one of Dante’s sons and possibly the rest of his family joined him there. Toward its completion, the Divine Comedy had made Dante revered as a poet, political critic, and regional celebrity. The Florentines offered to take him back into the city if the poet portrayed himself as penitent, which he refused to do.

In Ravenna where Dante’s body lies.

In 1319 Dante moved to Ravenna, lived comfortably there, and finished the Paradiso the following year, although the last thirteen cantos were retrieved accidentally months after his death. On a diplomatic mission Dante became ill and he died near Ravenna in September 1321.

Centuries after his death, Florence set up a tomb to house his body at the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, but Ravenna has no intention of letting Florence have him.

Dante’s tomb — or at least the one prepared for him — in the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence. It just needs the body.

time Neptune (in mid-Gemini) was in an opening square to Pluto (in mid-Pisces). More than any other planetary cycle, Neptune/Pluto is about the major turning points in a society and its culture.

time Neptune (in mid-Gemini) was in an opening square to Pluto (in mid-Pisces). More than any other planetary cycle, Neptune/Pluto is about the major turning points in a society and its culture.

Pluto and Neptune were in opposition in the early 1150’s, when Western Europe saw a tremendous amount of political and religious activity: the second Crusade had failed, the fight between Emperor and Pope for Northern Italy was beginning, and a conflict between religious conservatism and the new styles of philosophy had begun. (The third quarter square occurred in the early 1320’s soon after Dante’s death.)

Pluto and Neptune were in opposition in the early 1150’s, when Western Europe saw a tremendous amount of political and religious activity: the second Crusade had failed, the fight between Emperor and Pope for Northern Italy was beginning, and a conflict between religious conservatism and the new styles of philosophy had begun. (The third quarter square occurred in the early 1320’s soon after Dante’s death.)

1187: A Virtuous Pagan Takes Back Jerusalem. In this year Saladin and his force of Muslim troops recaptured Jerusalem and nearby Crusader States from their Christian occupiers. Although a non-Christian, Saladin was considered virtuous by his Christian contemporaries. (Unlike the Christians in the eleventh century he spared Jerusalem’s inhabitants when he captured the city.) We see Saladin in Dante’s first circle of Hell that is reserved for the virtuous pagans. The poet’s words require no translation: “e solo, in parte, vide ‘l Saladino.” (Inferno 4.129) The result of Saladin’s success was another invasion from the west that history calls the “Third Crusade.” This was the campaign that claimed the life of Frederick Barbarossa who accidently drowned. The Third Crusade ended in 1192 with a truce between Saladin and Richard “The Lionhearted” and there would be no further re-conquest of the Holy Lands

1187: A Virtuous Pagan Takes Back Jerusalem. In this year Saladin and his force of Muslim troops recaptured Jerusalem and nearby Crusader States from their Christian occupiers. Although a non-Christian, Saladin was considered virtuous by his Christian contemporaries. (Unlike the Christians in the eleventh century he spared Jerusalem’s inhabitants when he captured the city.) We see Saladin in Dante’s first circle of Hell that is reserved for the virtuous pagans. The poet’s words require no translation: “e solo, in parte, vide ‘l Saladino.” (Inferno 4.129) The result of Saladin’s success was another invasion from the west that history calls the “Third Crusade.” This was the campaign that claimed the life of Frederick Barbarossa who accidently drowned. The Third Crusade ended in 1192 with a truce between Saladin and Richard “The Lionhearted” and there would be no further re-conquest of the Holy Lands

fell in love with her on the spot. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure both die.

fell in love with her on the spot. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure both die.