A Bright Star in the Constellation

Arendt didn’t like television interviews: she didn’t want to be recognized on the street by strangers

In 1968 Hannah Arendt – political philosopher, essayist, and teacher — wrote a series of essays Men in Dark Times (including two women) that profiled exemplary people of her era. Early in this book she wrote, “even in the darkest times we have a right to expect some illumination. [This] may well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given them on earth.” (p. ix) In this essay the light is that of Hannah Arendt herself.

Over the past year or so, worried Americans have consulted Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism and some of her other works for perspective and guidance. Here’s an example, and here’s a longer one. An Internet search reveals an embarrassment of riches applying her works to our current political situation.

Over the past year or so, worried Americans have consulted Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism and some of her other works for perspective and guidance. Here’s an example, and here’s a longer one. An Internet search reveals an embarrassment of riches applying her works to our current political situation.

Hannah Arendt’s career began as a star among young German intellectuals; she became a Jewish refugee from the Nazis to France and then to the United States, where she became a citizen and well-known public intellectual and author. Although her contributions were many, she will forever be associated with the phrase “banality of evil”, the subtitle of her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem.

You may know about the controversies that came from this work; they were largely the subject of a recent movie Hannah Arendt (2013). In Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt depicted a uniquely modern dimension of evil, one arising not from monstrosity of character but from thoughtlessness. What are the dimensions of unreflective complicity and what are its costs? Later we will look at Arendt’s astrological indicators for writing this book and its negative reception.

Ten years before Eichmann she published the Origins of Totalitarianism that dissected systems of total social, economic, and cultural control and their high cost on being human. Originally conceived at the end of World War Two as an analysis of Nazism, she expanded her work to include the Stalinist Soviet Union as the Cold War was beginning. At the time this move was also controversial. Nonetheless, Origins has largely stood the test of history.

In 1958 she came out with The Human Condition a philosophical and historical analysis of the active – as opposed to the contemplative – life. She defined the political life as a life with others for its own sake, not subordinate to our being economic agents alone. In that way. she challenged Marxist socialism, laissez-faire capitalism and progressive liberalism.

These are only the best-known of Arendt’s writings. Aside from several other books, she frequently wrote for magazines and journals, using historical and philosophical perspective to shed light on contemporary matters. They included the Civil Rights movement and civil disobedience, Vietnam and Watergate, matters of revolution and political change. As a true philosopher, disagreeing with her helps to clarify one’s own thinking: this is a remarkable trait in our modern age.

Like Rachel Carson and Eleanor Roosevelt among our Exemplaries, Hannah Arendt had to muscle her way into fields of male dominance through native brilliance, willfulness, persistence — and making friends. Like all the others in this series, Arendt shed a bright light onto the perversity of their age, warned us of the future, and succeeded in leaving the world a better place than the world in which she lived.

Staying true to her own thinking, Arendt missed the importance of environmentalism in modern culture and her views on feminism are unknown. Her differentiation between private and public spheres and her questioning of the idea of natural rights missed the importance of civil rights legislation, that there could be effective legal responses to social prejudices. She could also come across as heartlessly objective, perhaps using irony as a personal defense, to the point of appearing insensitive. Perhaps these were necessary biproducts of having to be tough in a tough age. She smoked too much too.

Another Life to Give the Impression We’ve Done Nothing with Ours

Hannah Arendt was born of a German Jewish intellectual family in 1906;  her father died when she was young and she was raised in a strongly maternal environment. Intellectually gifted, Arendt received an outstanding education, attended university as an adolescent and received her PhD when she was 23. Her first mentor was Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a brief affair when she was a teenager, whose ideas strongly influenced her philosophical work and with whom she had a difficult but lifelong tie. She also studied with Karl Jaspers who supervised her dissertation; they remained intellectual and personal friends for life. Fresh with her diploma, Arendt was destined to be part of the next generation of influential German intellectuals. She married in 1929 and things appeared to be on track.

her father died when she was young and she was raised in a strongly maternal environment. Intellectually gifted, Arendt received an outstanding education, attended university as an adolescent and received her PhD when she was 23. Her first mentor was Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a brief affair when she was a teenager, whose ideas strongly influenced her philosophical work and with whom she had a difficult but lifelong tie. She also studied with Karl Jaspers who supervised her dissertation; they remained intellectual and personal friends for life. Fresh with her diploma, Arendt was destined to be part of the next generation of influential German intellectuals. She married in 1929 and things appeared to be on track.

A normal life was not to be for her, or for almost anybody else then. In 1932 Hitler and the Nazis took over Germany and its influence (including its ideology of anti-Semitism) began to pervade all areas of life and culture. Arendt had joined a German Zionist organization (similar to the Southern Poverty Law Center in this country) and was researching and recording the surging anti-Semitism in her country. Heidegger, as many of us know, was favored by the Nazis, joined their Party, and became an apologist for them. Arendt felt intellectually and personally betrayed by him. After she was questioned and briefly detained by the Gestapo, Arendt fled Germany.

Arriving in France, she then worked to help Jewish refugees fleeing Central Europe. She divorced her first husband and married a philosopher and former Marxist, Heinrich Blücher and they would stay married until his death in 1970. Once the Nazis took over in France, Arendt and Blücher were sent to separate internment camps. She escaped from her camp and reunited with her husband. Using forged visas, they obtained safe passage and went to the United States. When she arrived in this country she felt she had entered paradise.

Into America

Learning English at record speed, Arendt joined the community of German Jewish emigres in the United States and was a frequent writer for that community. During this time she wrote an essay “Zionism Reconsidered” where she voiced fears that establishing a Jewish state in Palestine would lead to decades of conflict with those already there. After the war Arendt was involved in rescuing thousands of Holocaust victims from Europe and helping them settle in the region that became Israel. She also resumed her academic career.

By 1950 she became a US citizen and pursued her academic career in a variety of places, frequently being a visiting professor and giving series of lectures, but never settling down as a tenured professor. Her husband taught at Bard College for many years. Arendt had a “genius for friendship” and had a strong circle of friends and intellectual collaborators from Europe that included some leading intellectuals in the United States.

When Origins of Totalitarianism was published she became instantly famous although she shunned personal celebrity and distrusted fame. The Human Condition, a more difficult work, nonetheless succeeded in branding her as one of America’s leading intellectuals.

In 1960 agents of Israel kidnapped Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and flew him to Israel. Eichmann, the most famous Nazi on the run at that time, was a leading organizer of the “final solution” of the fate of European Jewry. Arendt approached the New Yorker and became their correspondent to cover Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem: she hadn’t ever met a Nazi leader.

In 1960 agents of Israel kidnapped Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and flew him to Israel. Eichmann, the most famous Nazi on the run at that time, was a leading organizer of the “final solution” of the fate of European Jewry. Arendt approached the New Yorker and became their correspondent to cover Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem: she hadn’t ever met a Nazi leader.

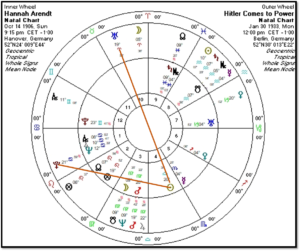

I now break the narrative of her life and present her astrological natal chart. It’s a remarkable chart.

The Triumph of Jupiter

The first thing to notice is her Ascendant in Cancer and two degrees away is Jupiter, exalted in Cancer and conjunct Neptune. Jupiter is the dominant planet in her natal chart; no other planet comes close. Modern astrologers often depict Jupiter as a planet of ideology, “confidence”, and overdoing everything. Jupiter is bigger than that.

One important traditional signification for Jupiter, particularly relevant to Arendt thinking, is that of participation beyond the personal and domestic, inclusion into larger spheres of life. This clearly brings us into the cultural and political life of a community. The western philosophical tradition tended to promote the contemplative life over the active life, the individual over public, logic over rhetoric, mathematical truth over human opinion.

According to this line of thinking, community inclusion carries with it the temptation to lose oneself in the crowd.

The Human Condition is an attempt to reverse this. Toward the end of her life she took up the matter of contemplation in her unfinished Life of the Mind, yet for her withdrawal and reflection are prelude to a more genuine participation with others.

Although an “honored guest” as exalted in the sign Cancer, Jupiter is out of sect in her nocturnal chart. Although she continually asserted the need for community involvement, personally she was somewhat reserved and not made of the stuff of celebrity or notoriety. Although quite sociable with friends, students, and other writers, she particularly liked the lines by W. H. Auden, another friend of hers.

Private faces in public places

Are wiser and nicer

Than public faces in private places

The combination of Neptune with Jupiter is famous for over-idealizing, for finding certainty in fantasy, or, in the First House, presenting a grandiose or glamorous portrait of oneself to the world. Jupiter’s strength in its sign of exaltation seems to prevent it from being seduced by Neptune’s fantastical tendencies. Here these planets seemed to operate in tandem, and perhaps this resulted in being visionary. At the same time, we can also see in her work an attempt to correct her era’s tendency toward all-consuming ideologies, mindless bureaucracies of evil, people as numbers. Perhaps it was from a visionary outlook for Arendt to continue promoting the virtues of the political process, in spite of breakdowns in Europe and elsewhere.

It is interesting to work with Arendt’s Human Condition in this age of global – but not local – interconnection and an increasingly fluid sense of community. Arendt asserts herself as a civic republican. The Human Condition asserts that the political life, that of interchange (what Americans like to call the “marketplace of ideas”) and rhetoric and persuasion and opinion – “speech” – is fundamental to what makes us human. She divides the active life into labor, that which sustains our physical being, work that is the creation of items meant to last, from highway construction to poetry, and action that describes a life among others that is ongoing and open-ended. Diverging from Martin Heidegger’s focus on Being-toward-Death of the individual, Arendt focus is on “natality”, the fact that each of us is a unique irreplaceable being, even if only on this planet temporarily. We are neither the same nor different from others, instead we are together with them. In this way, people together are capable of enormous creativity in responding to complex situations. Participating in the life of the “city” or polis is by nature ongoing, without beginning or end, with uncertain outcomes that we are nonetheless responsible for. Of course, we may try to flee this responsibility to focus solely on wealth, or by becoming one-sided and ideological, or by surrendering autonomy to a charismatic strongman.

Sun, Moon and a Guest

Arendt’s Sun is in fall in Libra, is out of sect in a nocturnal chart, and is unaspected by other planets. In part, the Sun symbolizes one’s arenas of personal identity and identification; it embodies the creative use of life’s situations for the purposes of self-expression and growth. Sun in Arendt’s Fourth House shows her identity with and loyalty to her ethnic group but also her country of origin and its language, something that would characterize her throughout her life, even in the light of the Nazis, war, and Holocaust.

Let’s hold this in mind as I discuss the Moon’s position in her chart: Moon in Virgo in the Third House, in its triplicity in her nocturnal chart. In part Moon is about our ability to adapt, to ride along with changing circumstances, and in her case especially, to accommodate adverse circumstance and maintain oneself somehow. Moon is in its “joy” in the Third House, called the place of the “Moon Goddess” by ancient astrologers. This placement was associated with prophecy, with spirituality as a personal more than a public concern.

Moon in Virgo is intelligent and careful, and, at its best, responds to adversity with toughness; Virgo can render the Moon cooler and more calculating, less emotionally expressive than elsewhere. Moon in Virgo also knows how to be a part-player in a large spectacle with a large cast. In her case, the horrors of her lifetime were the large spectacle, and her job was to understand, communicate, and use her intellect to help things be better in the future. It was not to express that trauma personally or emotionally.

When we look at the Sun and Moon together we note that the Sun at 20° Libra and Moon at 9° Virgo are symmetrical to 0 ° Aries: they are connected through being in contra-antiscia to one another. When we look at Saturn in Pisces opposing Moon, we have a similar configuration: Sun and Saturn are in antiscia to one another.

Saturn opposite Moon

Saturn, the cold dry planet at the end of the visible solar system, is the planet of melancholy and oppression and hardness. Saturn is also the planet of contemplation. In Arendt’s chart Saturn is wholly out of sect – the chart is a nocturnal nativity, Saturn is in the opposite hemisphere from the Sun, and is in the feminine sign Pisces. Cold dry Saturn is a natural adversary of the warmer and wetter and more personal Moon, even a Moon in Virgo. This combination doesn’t exactly give Moon a soft touch.

Saturn is Pisces gets a trine from Jupiter in Cancer; Jupiter is in its exaltation in Cancer and is also applying to Saturn that’s in Jupiter’s sign Pisces — between the two Jupiter prevails. In many areas of life Arendt’s Saturn flourished, working particularly well for her as a young philosopher and later as an important interpreter. Like her mentor Martin Heidegger, Arendt’s writings endeavored to bolster the authority of the western intellectual tradition and its “original” formulations in Greece. (This reminds us that Saturn is in the Ninth House.)

We return to Moon in Virgo that, in addition to its opposition from Saturn, has sextiles from the other side from Neptune and Jupiter. Moon in Virgo adds a measure of practicality to the idealism of her Jupiter-Neptune combination. Virgo is also the toughest of the mutable signs and this contributed to her unsentimental and exacting style. Arendt was not your typical “nurturing” Cancer-rising person!

Mercury Takes the Stage

Mercury in Scorpio applies to Saturn in Pisces. Scorpio can be a strong position for Mercury if it takes advantage of the focus, fixity, and Mars-like penetration of Scorpio. The trine to Saturn makes hard work and rigorous study possible but also makes depression and despondency possible, although the trine relationship makes it less likely.

Arendt’s Mercury is an “evening riser”: it is moving away from the Sun, having a faster daily motion than the Sun on her day of birth and afterwards, and emerges from the Sun sets in the evening. This gives Mercury both a degree of visibility but also the retentiveness and introspection of being of a nocturnal sect, occidental to the Sun.

On the day of her birth, Mercury was culminating with the pioneering fixed star Arcturus. Mercury’s exact sextile to Uranus in the Seventh House certainly helped her be an original thinker.This is yet another indication of her continuing legacy as an interesting and innovative thinker.

More on Mars and a Little on Venus

Mercury is also connected to Mars in Virgo through mutual reception: Mars is one lord of Scorpio and Mercury is one lord of Virgo. Additionally, the two planets’ signs are in signs in sextile to one another. Arendt carried with her a power of conviction, perhaps a certainty of conviction. Once again we see mental toughness that can be strengths but also sources of difficulty. However, Mars is in sect in her nocturnal chart and will more likely incline to advantage but with a price to pay.

Mars is in square to Pluto and this seems obvious, considering her life and the times in which she lived. Mars in Virgo is generally not forgiving of fools and the square to Pluto in the Twelfth gave her the soberness and clarity, to make a lifetime study of the origins and varieties of evil in her century, to attempt to bracket her personal emotions and be a good witness.

Venus has an unusual character in Hannah Arendt’s chart. It’s in the difficult Sixth House but in Sagittarius, governed by Jupiter. It’s also applying to a square to Saturn and is the ruler of her Lot of Spirit in the Eleventh (Sun is lord of her Lot of Fortune in the Second House.) Venus is quite visible in the evening but is slowing down, going toward retrograde when the Sun catches up to it by thirty degrees.

It’s not an easy placement and would not add sparkle or glamour but is not without appeal, within her own comfort zone; she had to rely upon being brilliant and interesting. As the ruler of the Eleventh House, Venus accounts for her “genius at friendship” and for her strong marriage that was also a friendship. We also note that Venus is square her Midheaven degree; on its own this is not a major factor, except that Venus will be included in any transits that involve her Midheaven/IC axis. Stay tuned.

Predictive Indicators Earlier in Her Life

Eighty-five years ago, was a Uranus-Pluto square previous to this one: from 1931 to 1933 Uranus was in Aries, as it is now, but then Pluto was in square from Cancer. The square was exact in 1932, Uranus was opposite her Sun and Pluto square her Sun.

The Pluto-Uranus square symbolizes well the effect of Hitler’s coming to  power on her: it would end her career as a German academic and affiliate her with her Jewish background. This powerful transit thus began her personal and professional odyssey that would mirror events in the world and help give to us what she is best known for today.

power on her: it would end her career as a German academic and affiliate her with her Jewish background. This powerful transit thus began her personal and professional odyssey that would mirror events in the world and help give to us what she is best known for today.

Her progressions for this time included a waning third-quarter Sun-Moon square, Venus going stationery retrograde, and her progressed MC (by solar arc) going into Aries. Any life of contemplation ended and an active life began. At that time, her decennials were Sun-Saturn. Soon she began her life as an exile and immigrant, reflecting Saturn’s influence.

Continuing with her secondary progressions and fast-forwarding to 1939, we would see a progressed New Moon and a progressed square completed between Mars and Jupiter. Remember this was when the Nazis invaded France and she was sent to a detention camp. Her decennials then became Mercury-Mercury that points to a change of residence, and maybe that of language. By the middle of 1940 Arendt had fled from the authorities to the United States where she would live for the rest of her life

The Matter of Eichmann

We resume our narrative.

After attending Eichmann’s trial and engaging in intensive research and reflection, her observations were first published in the New Yorker magazine in February 1962. They were expanded in her full-length book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. She questioned the legitimacy of the trial itself, since it seemed more like a political show trial than a serious legal tribunal. She was struck that Adolf Eichmann was a “nobody” who spoke mostly in clichés, who demonstrated no ability to think for himself or to make common-sense moral judgments. Instead Eichmann was focused on his career and his ability to be a really good manager. Here’s the first installment of her articles in the New Yorker from 1963.

Her depiction of Eichmann continues to be controversial, as further information about him has come to light: perhaps he was more monstrous than he appeared to her from behind the glass cage. Yet her understanding of those who participate in state-sponsored atrocity continues to be influential.

More controversial and painful to her was her allegation that the European Jewish leadership had been too hopeful, too cooperative with the Nazi authorities. She stated that had the Jewish community in Europe been less organized than it was, it would have been more difficult for so many people to be sent to their deaths. What in Arendt’s mind was an illustration of the “totality of the moral collapse the Nazis caused in respectable European society” was perceived by many to be blaming the Holocaust’s victims. This seemed to contrast with her softer treatment of Eichmann himself, it was alleged. This criticism, promoted by some and refuted by others, created quite the stir, compromised her academic reputation, and lost her many life-long friendships. In the 2013 movie there’s a short scene in which she is depicted as defending herself, with more vehemence that she would do in real life: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wmBSIQ1lkOA&t=114s

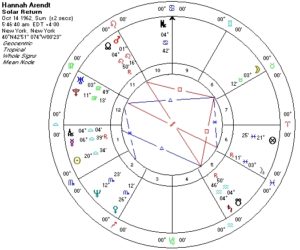

1962, during which she was researching and writing, began with a Progressed Third Quarter Moon, from Virgo to Sagittarius. Following Dane Rudhyar’s depiction of the Progressed Lunation Cycle, this is a time of fulfillment and culmination, but also beginning to wrap up old business. Her work on Eichmann finished her work that began when she began Origins of Totalitarianism twenty years before.

Her Secondary Progression also revealed Mercury at station to go retrograde in October at twenty-nine degrees Scorpio. She came into the Eichmann trials expecting an extension of her ideas of the radical evil of totalitarianism and instead she encountered an organized but hollow nebbish. Mercury going retrograde at this time, refusing to leave Scorpio for Sagittarius, allowed her a fresh new look and to understand another dimension of human frailty in the face of evil.

Her decennials had been Saturn-Saturn since late 1959 and changed to Saturn-Jupiter in March 1962. This change appears to have occurred in the nick of time, for she needed the resources of her strongest planet to navigate what would come next for her.

Her solar return for 1962 that would include her publication and its immediate aftermath tells us much. The solar return Midheaven degree is very close to her natal Ascendant degree, showing us that this would be an important year for her interaction with the world. Solar return Mercury is very close to solar return Ascendant and the Sun is also in the First – this would be a year in which her ideas and her presence would be visible, if not exactly pleasing. The Moon, ruler of the Tenth House in the solar return is placed in the difficult Eighth House, is in exaltation in Taurus but it is otherwise strongly afflicted. Moon has completed a square to Mars and is applying to Saturn, what the medieval astrologers called “besiegement”. This was a public but difficult time for her.

Her solar return for 1962 that would include her publication and its immediate aftermath tells us much. The solar return Midheaven degree is very close to her natal Ascendant degree, showing us that this would be an important year for her interaction with the world. Solar return Mercury is very close to solar return Ascendant and the Sun is also in the First – this would be a year in which her ideas and her presence would be visible, if not exactly pleasing. The Moon, ruler of the Tenth House in the solar return is placed in the difficult Eighth House, is in exaltation in Taurus but it is otherwise strongly afflicted. Moon has completed a square to Mars and is applying to Saturn, what the medieval astrologers called “besiegement”. This was a public but difficult time for her.

Now for her transits. Transiting Jupiter was in Pisces in 1962 and in April 1963 it moved into Aries and her Tenth House of career and reputation. Especially with the corroboration of her solar return, this could be a time of greater visibility for her. Indeed, she saw more press coverage and more interviews but there was nothing pleasant about this.

When Uranus and Pluto were transiting her Sun, Hitler came into power; now, thirty years later and coinciding with the Eichmann controversy, these same two planets were moving toward their conjunction that would take place in the mid-1960’s.

Beginning in 1959 transiting Pluto was at her IC and in square to Venus. After that transit had finished it was Uranus’ turn and then Uranus was making the same transits to Venus and Midheaven but was now accompanied by Pluto conjunct Moon and opposing Saturn. What a lineup!

It’s often in our lives that the personal and public/career dimensions of our lives work differently, so that if one is difficult the other can be a source of support. In Arendt’s case, after the publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem, the public and private areas of life were both shaken up. Her own toughness and confidence and her strong friendships and marriage managed to carry her through this difficult time.

Epilogue

German postage stamp bearing Arendt

Arendt soldiered on, of course, continuing her career writing and teaching and commentating on world events surrounding her. Over time the din dimmed and she found herself rewarded with honorary degrees and prizes, in the United States and internationally.

Her husband was in diminishing health during the last decade of their life together and this only increased the stress in her life. When Heinrich Blücher died in autumn 1970 she has lost a companion, intellectual partner, and someone’s whose spontaneity and outgoing passion could balance her tendency toward reserve and self-control. In the next few years her friends Karl Jaspers and W.H. Auden also died, leaving her feeling more isolated and alone.

During the final years of her life, with her health beginning to fail, she returned to philosophy from politics and began to work on an analysis of the inner life that would be edited and published posthumously as the incomplete Life of the Mind. Her emphasis continued to be on the individual’s contribution to the world, from the viewpoint not of active participation but the required withdrawal and introspection – conversation with oneself leading into judgement — from which one re-emerges back into the world.

In December 1975, while entertaining friends in the evening, Arendt had a heart attack from which she never regained consciousness and died  before her doctor arrived. She is buried at Bart College alongside her husband.

before her doctor arrived. She is buried at Bart College alongside her husband.

And, as stated above, there is currently a revival of interest in her work, extending its relevance into current social and political situations. I don’t know the positive side of “turning over in one’s grave” but this would be it.

My last two profiles featured individuals who warned us about totalitarianism in the last century — the next one features one who had to live under it as an artist.

This is cool, Joseph. Thanks for writing it. I need to read some of Arendt’s work.