![[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section] Nikon D100 2004/06/23 20:36:45.8 RAW (12-bit) Lossless Image Size: Large (3008 x 2000) Lens: 70-300mm f/4-5.6 D Focal Length: 100mm Exposure Mode: Programmed Auto* Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern 1/6 sec - f/16 Exposure Comp.: 0 EV Sensitivity: ISO 200 White Balance: Auto AF Mode: AF-S Tone Comp: Auto Flash Sync Mode: Not Attached Color Mode: Mode III (sRGB) Hue Adjustment: 0° Sharpening: Auto Noise Reduction: OFF Image Comment: [#End of Shooting Data Section]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/newport_prudence_island-boats_narragansett_bay_1-300x105.jpg)

The weeks previous to the New Year were, of course, our annual “holiday season” where there is much excess, much connectedness and personal and family complexity. This is also when loneliness hurts far more than usual. It is a time of unusual joy that it is often emotionally wrenching. This is reflected in traditional holiday literature and in our holiday movies. It is no accident that the two best-known modern tales of the holiday season, Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and O. Henry’s Gift of the Magi involve grappling with poverty and deprivation. From A Charlie Brown Christmas to It’s a Wonderful Life to The Apartment, dark occasions are broken by a shaft of light coming only at the very end.

Traditionally “Christmastide” was from Christmas Eve to Epiphany on January 6, the days following the winter solstice. Once upon a time it was Advent, not post New Year, which was for fasting and reflection; today our pre-Christmas weeks are for shopping, office parties, and intra-family gift-giving negotiations. The origins of the “holiday season” are the changing light and dark in the North Hemisphere, when the long nights begin to give rise to more sunlight and the intimation of a new beginning. The word “solstice” means “Sun stands” and reflects the fact that the lengths of the days do not change within several days of the Sun’s limit of southern declination, its ingress into Capricorn.

At what time do the days begin to noticeably lengthen? It begins around New Years Day. From Providence, RI, at the solstice the day is 8 hours and 56 minutes; by January 1 it has become 9 hours and one minute. (By the middle of January, the day’s length has grown to 9 hours 19 minutes.) New Years Day begins the visible reassertion of light and is similar to a very thin crescent Moon one day after an invisible New Moon. This is a new beginning – but what lies beforehand is the true matter of the winter solstice and its “holiday season”.

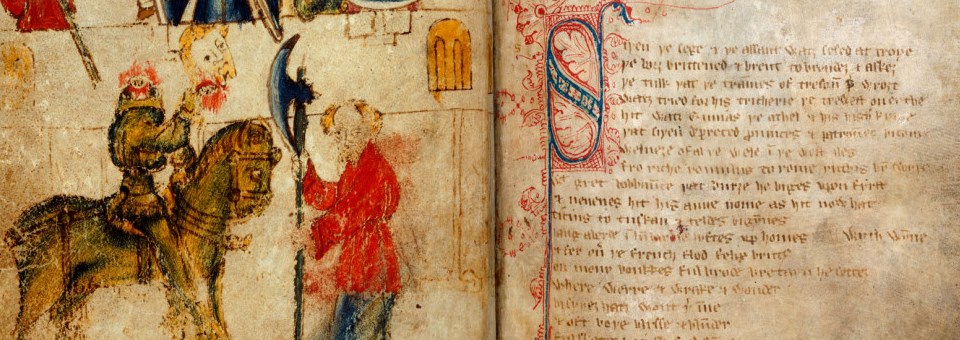

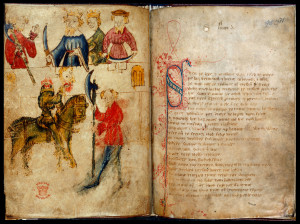

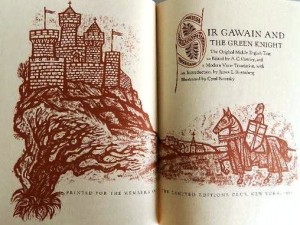

During this holiday season I have been re-reading a remarkable anonymous work of the latter middle ages, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a poem of about 2500 lines. Two years ago I presented an article on the poem as a solstice tale, and this year I have enjoyed developing this material further.

The Text of Sir Gawain

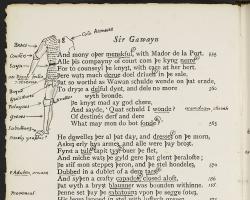

It is miraculous that we have this work today: only one manuscript survives from the fourteenth century. It was uncovered in a scholar’s library in the nineteenth century, and today is renowned as one of great English-language poems of the Middle Ages. It is roughly contemporary with the works of Chaucer. Its language, however, is more difficult to understand than Chaucer. Fortunately many translations are available for the general reader. There has been a great deal of scholarship on the work since its discovery, including an annotated version by JRR Tolkien, and commentary by C. S. Lewis and many others.[1] Interest in the poem continues to this day.

The Gawain poem is a meditation on the possibilities and limitations on the extent of human goodness, on the relationship between outer disposition (and reputation) and inner character, and between the inevitable disjunction between the two. As a meditation on the dark and light of human nature, its outer manifestation is seen in the tribulations and renewal of the winter solstice holiday season.

The Green Knight and his Challenge

The opening is in King Arthur’s court at Camelot and the poem begins on Christmas Day. The seasonal festivities last several days and are splendid – there is much food, dancing, and merriment within an uplifted elegant social environment. This is a young court and its king is also quite young. What is about to happen will make this festive gathering seem, naïve, a bit too tidy and absorbed by its too-self-consciousness upliftedness.

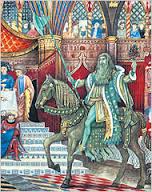

On New Year’s Day gifts are exchanged and a great meal is readied. King Arthur waits to eat in the hope that something truly interesting will happen, perhaps somebody will tell an exotic tale. Arthur then gets his wish in abundance: breaking into the festivities is a tremendously large knight riding a horse – certainly an unusual event and a major intrusion onto this cozy indoor setting. The poet’s narrative pauses while he describes this knight and horse at length, focusing on the knight’s imposing physical size and commanding form, his well-decorated garments (but no shoes). The Knight wears neither helmet nor armor, and in one hand is a sprig of holly and in the other a large deadly axe. His horse is arrayed as splendidly as he is.

On New Year’s Day gifts are exchanged and a great meal is readied. King Arthur waits to eat in the hope that something truly interesting will happen, perhaps somebody will tell an exotic tale. Arthur then gets his wish in abundance: breaking into the festivities is a tremendously large knight riding a horse – certainly an unusual event and a major intrusion onto this cozy indoor setting. The poet’s narrative pauses while he describes this knight and horse at length, focusing on the knight’s imposing physical size and commanding form, his well-decorated garments (but no shoes). The Knight wears neither helmet nor armor, and in one hand is a sprig of holly and in the other a large deadly axe. His horse is arrayed as splendidly as he is.

Knight and horse have a most unusual distinguishing feature – in skin and clothing, they are both very green – not dark green but green like the summer grass. They storm into the fancy goings-on at Camelot like the clichéd “bull in the china shop.” His presence is both opulent and utterly wild, like the color green itself. We do not know who he is or his motive until the end of the poem.

This mountain of a knight approaches the court, asking who is in charge around here. The assembled group gapes in amazement and finally Arthur identifies himself. The Knight states that he has come not with a challenge to fight but with a different kind of challenge that he calls a “Crystemas gomen” [Christmas game]. If one of these brave men cuts off his head, he will return the favor in one year’s time. All are stunned speechless; in response he ridicules the assembly for being hidden cowards. Here are the lines in their original – using the modern English alphabet.

“That al the rous rennes of thurgh ryalmes so mony?

Where is now your sourquydrye and your conquestes,

Your gryndellayk and your greme and your grete words?

Now is the revel and the renoun of the Rounde Table

Overwalt with a orde of on wyyes speche,

For al dares or drede without dynt schewed!” (309-315)[2]

Here’s a translation by M.S. Merwin:

“That all the talk runs on through so many kingdoms?

Where is your haughtiness now, where are your triumphs,

Your belligerence and your wrath and your big words?

Now the revel and renown of the Round Table

Are overturned by the word of one man alone, All cowering in dread before a blow has been struck.”[3]

A Note about Poetic Style and Translation

I choose Merwin’s translation because it adheres closely to the Gawain poet’s language and would give the reader more direct access to the original text. However, there are other translations that are closer to the poet’s verse style.

Sir Gawain is written in alliterative verse, whereby each line contains four stressed syllables, the first three of which begin with the same initial letter. It is easy to pick up from the text: the first line repeats the sound “th”, the second line “r”, to the eighth line that features repeated “d”. You can also see that not each line follows the same formula. (There are also rhymed quatrains that conclude each small section.) This style of alliterative verse can be replicated in modern English and here are two other translations of the same passage.

Sir Gawain is written in alliterative verse, whereby each line contains four stressed syllables, the first three of which begin with the same initial letter. It is easy to pick up from the text: the first line repeats the sound “th”, the second line “r”, to the eighth line that features repeated “d”. You can also see that not each line follows the same formula. (There are also rhymed quatrains that conclude each small section.) This style of alliterative verse can be replicated in modern English and here are two other translations of the same passage.

This is from Marie Boroff and the same lines translated by Simon Armtage.[4]

Modern English lends itself easily to the alliterative form of the original verse by the Sir Gawain poet, and both versions here are pleasing to read and capture the spirit of the original if not its vocabulary. Although I love the work of Boroff and Armitage, I will continue to use Merwin’s translation in this essay.

The Game Begins

We return to the story. Somebody must take up the Knight’s challenge and King Arthur himself approaches the Knight, telling him that although the Knight’s challenge is insane he will take him up on it to uphold the pride of his court. Arthur has already raised the axe when suddenly Gawain, seated next to Queen Guinevere, interrupts. He will take up the challenge: the King is too important to take up this insane challenge: “I am the wakkest, I wor, and of wyt feeblest,/And lest lur of my lyf, quo laytes the soothe…” (354-355) Or, as according to Merwin, “I am the weakest, I know, and the least wise,/And cling least to my life, if anyone wants the truth…” This sounds noble and high-minded, except that his words do not ring true.

We return to the story. Somebody must take up the Knight’s challenge and King Arthur himself approaches the Knight, telling him that although the Knight’s challenge is insane he will take him up on it to uphold the pride of his court. Arthur has already raised the axe when suddenly Gawain, seated next to Queen Guinevere, interrupts. He will take up the challenge: the King is too important to take up this insane challenge: “I am the wakkest, I wor, and of wyt feeblest,/And lest lur of my lyf, quo laytes the soothe…” (354-355) Or, as according to Merwin, “I am the weakest, I know, and the least wise,/And cling least to my life, if anyone wants the truth…” This sounds noble and high-minded, except that his words do not ring true.

Gawain is Arthur’s best knight and is renowned for his courage in battle and his courteous manner and goodness of character. His self-deprecating remarks seem a bit too theatrical, too much a performance of noble character than an honest self-assessment.

The Green Knight dutifully bares his neck and Gawain raises the mighty axe and severs the Knight’s head. However, a bizarre thing occurs: the Knight – or what’s left of him – lowers his hands, finds the head, raises it above, returns to his horse, and the head tells Gawain to find him at the “Green Chapel” next year for his return favor. Gawain does not know where the Green Chapel is.

Instead of joyful illumination, this year’s New Year’s light has brought dark intrusion into a gathering overly taken with its own youthful exuberance. Yet, as the door shuts behind the Green Knight and his horse, the laughter and partying resume.

One might expect from the Knight’s strikingly odd appearance, that he would have supernatural powers. Now the tables are turned. If the Knight strikes him as he struck the Knight, Gawain will lose his head. But where does he find the Knight and his Green Chapel? He must journey to an unknown destination to find the Knight and meet certain death.

Into the Middle of Nowhere

As the second part begins, the seasons quickly pass from winter to spring to summer. We take up the action at the holiday of Michaelmas (September 29), for Gawain must soon set out for the Green Knight and his Chapel. This is about a week after the autumn equinox, when the dark of the night overtakes the daytime. Set in the area of Wales and North Wales which are of high northern latitudes, the days would be getting shorter very quickly by now.

A month later the length of night has increased a great deal; this is the time of the cross-quarter season and near the holiday we know now as Halloween. According to the Christian calendar it was All Saints Day and that’s when King Arthur’s court would gather to say a very sad goodbye to its esteemed knight.

Before his departure, Gawain is readied for the contest and receives a brilliant interlaced gold pentagram engraved on his shield that represents all the virtues he could possess. Perhaps they are representative of his idealized public self. There were five groups of five qualities symbolized by the five sides: five faultless senses, five fingers that would not fail him, five wounds of Christ, five joys Mary had for her child Jesus, and five specific virtues of a knight: friendship, fraternity, purity, courtesy, and compassion. On the inside is an image of Mary. Although the poet describes this pentangle in great detail, the poet never mentions any subsequent use and it is only referred to once at the end of the story.[5]

With fanfare and great sadness Gawain leaves the court, for he will probably not return.

Gawain’s journey to find the Green Knight and receive the return blow of the axe is cold, rainy, and lonely. He is in the middle of a dark nowhere, and has had to battle strange creatures to keep going. By Christmas Eve he is completely depleted and desires to find a Christmas mass. He prays to Mary for help, and suddenly Gawain sees castle walls in the distance, surrounded by a moat. He approaches the castle, asks for hospitality, and is let in.

Gawain has suddenly entered another seasonal festivity. Gawain meets the lord of the castle, a burly affectionate man. The lord and his party are pleased that such a noble knight would be among them for their Christmas celebrations. They tell him that the Green Chapel is close nearby and he should spend time with them before he meets the Green Knight.

Gawain has suddenly entered another seasonal festivity. Gawain meets the lord of the castle, a burly affectionate man. The lord and his party are pleased that such a noble knight would be among them for their Christmas celebrations. They tell him that the Green Chapel is close nearby and he should spend time with them before he meets the Green Knight.

Soon it’s time for mass (there’s a lot of church-going in this castle.) Gawain meets the lord’s very lovely wife who he later sees accompanied by an old woman who is anything but beautiful. Our hero particularly enjoys their company. For the next three days Gawain is wined and dined and has a great time among his new friends.

On St. John’s Day that is December 28, the feasting ends. Since there a few days before New Years, the lord proposes a game to Gawain. Between the celebrations of Christmas and New Years Day the lord of the castle is to go on hunting. Each evening on his return he will bring home to Gawain any of his winnings. Gawain, who can lounge around the castle and hang out with fine company, will give to the lord his winnings of the day. So ends the second part.

Stalking Prey

What comes next is for me the most delightful and riveting part of the poem. The poet goes back and forth between the outdoor scenes of the hunting expedition and the indoor scenes of Gawain and his trials, setting up juxtaposition between them.

The lord’s hunting meets with declining results: on the first night he has many deer to offer to Gawain, on the second night a huge boar, and in the third one returns with only a small fox. The narrative of the hunt and its aftermath is vividly and realistic, including much detail about the ways to render the animal carcasses ready for eating. These exploits are told as if the poet was writing heroic epic.

Another form of the hunt occurs in Gawain’s bedroom, and we have now entered the realm of romance. At this time the poet begins to focus on the subjective thoughts and feelings of the noble protagonist. On the first morning, lying in bed, he hears the sound of somebody entering his bedroom, and it’s the lord’s lovely wife who plans to seduce him. Having previously noted that this woman was even lovelier than King Arthur’s wife Queen Guinevere, and since the lady proved herself expert at love’s discourses and the conventions of courtly love, she is a mighty adversary in her own right. Finally, he allows her to give him a kiss before she departed, a kiss that is duly rendered to the lord upon his arrival from his day of hunting.

Another form of the hunt occurs in Gawain’s bedroom, and we have now entered the realm of romance. At this time the poet begins to focus on the subjective thoughts and feelings of the noble protagonist. On the first morning, lying in bed, he hears the sound of somebody entering his bedroom, and it’s the lord’s lovely wife who plans to seduce him. Having previously noted that this woman was even lovelier than King Arthur’s wife Queen Guinevere, and since the lady proved herself expert at love’s discourses and the conventions of courtly love, she is a mighty adversary in her own right. Finally, he allows her to give him a kiss before she departed, a kiss that is duly rendered to the lord upon his arrival from his day of hunting.

The second day goes in a similar way, although the lady’s seductions were becoming more overt. Upon the lord’s return he receives another kiss from Gawain. During the evening, the lord’s wife talks to Gawain continuously, exchanging talk and good humor, while the virtuous knight becomes more and more agitated. Anticipating his upcoming meeting with the Green Knight, Gawain’s sleep that night is troubled.

On the third morning, the lady enters his bedroom once again and this time dressed in a decorous but revealing way. Gawain is caught is a terrible dilemma, made no easier by this woman’s attractiveness and his growing desire for her.

Here’s the poet’s summary of Gawain’s problem, followed by Merwin’s translation.

Nurned hym so neghe the thred, that nede hym behoved

Other lach ther her luf other lodly refuse.

He cared for his cortaysye, lest crathayn he were,

And more for his meschef, yif he schulde make synne

And be traytor to that tolke that that telde aght. (1770-1175)

The social and celebratory gathering at the castle has now become its own battlefield where our own natural desires have become vulnerabilities, where conviviality and social conventions have become instruments of battle. The poet has given us the darker and more dangerous side of the community festivity of the Christmas season.

During this third encounter between virtuous knight and beautiful woman, she kisses him three times and proposes that they exchange gifts. Gawain refuses two gifts, for he had nothing to give in return. Then she offers him her green girdle – more like a belt or sash – that, she says, would protect its wearer from being struck by another. Fearing for his life the next day when he is to meet the Green Knight, Gawain thinks this is a really good idea and takes the girdle from her. Eventually she leaves and he goes to confession – most important since he will probably die the next day – and afterwards is joyful that his soul has been cleansed. Later, when he and the lord of the castle exchange gifts, Gawain gives his host three ardent kisses but hides the girdle from him.

Gawain Unhinged

The next day (and the beginning of the fourth part) is New Year’s Day and Gawain sets off early with his horse and a servant for the Green Chapel. The servant tells Gawain how murderous and coarse is the dweller of the Chapel and Gawain replies that nonetheless he must honor his pledge. The servant happily parts company and Gawain must now face the Green Knight alone.

Gawain continues to look around for this Chapel. At last he sees a little hill that is no real chapel at all but a mound that, upon closer examination, has holes on two sides and is hollowed-out inside. It appears indistinguishable from the ugly and cragged landscape of his day’s travel. To Gawain it looks like the place of the devil.

Now he hears the sounds of an axe being sharpened. Appearing is the Green Knight looking just as he did one year before at Camelot. They exchange insults and Gawain puts his head on the chopping block. At the last moment, however, Gawain flinches and the Knight stops and insults him for his cowardice. The Knight raises the axe for a second blow, but also stops in the middle. Now comes one more attempt and the axe falls down on Gawain but only nicks the side of his neck, drawing enough blood so that Gawain sees red drops on the snow, and he knows he’s still alive. Gawain jumps up – his part of the agreement has been served! Suddenly he is a very happy man.

Now he hears the sounds of an axe being sharpened. Appearing is the Green Knight looking just as he did one year before at Camelot. They exchange insults and Gawain puts his head on the chopping block. At the last moment, however, Gawain flinches and the Knight stops and insults him for his cowardice. The Knight raises the axe for a second blow, but also stops in the middle. Now comes one more attempt and the axe falls down on Gawain but only nicks the side of his neck, drawing enough blood so that Gawain sees red drops on the snow, and he knows he’s still alive. Gawain jumps up – his part of the agreement has been served! Suddenly he is a very happy man.

But the story is not over. Leaning on his axe, the Green Knight explains that he is also the lord of the castle where Gawain was staying and that the behavior of his wife was part of the game that was to test him. On the first two days Gawain passed his tests with flying colors by giving the Green Knight back the kisses Gawain had received from his wife. However, on the third day Gawain failed by not returning to the lord the green girdle and kept it for himself. This small fault has now been repaid by a small nick on his neck. (By implication, if Gawain had given into the lady’s seductions or treated her harshly and therefore insulted her and his host, he would have been beheaded by the Green Knight.)

The whole thing was at the behest of Morgan le Fay, who was the old woman who accompanied his wife and had supernatural powers, to test Gawain’s and Camelot’s pride and its noble character. Gawain has shown himself to the Knight to be extraordinarily virtuous. Acknowledging the role of his wife, he says,

Here’s Merwin’s translation.

At first Gawain is speechless but then speaks angrily, cursing the “cowarddye and covetyse bothe” that are the cause of so much unhappiness and faults that he also has. He takes off the girdle, this treacherous thing, and angrily throws it to the Knight. He calls himself cowardly, disloyal and a liar. Gawain clearly has a different perspective from that of the Knight.

The Green Knight gives Gawain back the girdle as a reminder of their meeting, and invites him back to the castle and to partake of his and his wife’s hospitality. Gawain refuses, now going into a general diatribe against women. The Green Knight offers him the green girdle; Gawain accepts it and will wear it as a token of his failure: it has a different meaning for him. At his wit’s end, Gawain behaves in a manner very different from how he has been seen previously. Although he seems out of character, we now see him as a fuller person. Happy New Year, Sir Gawain!

Gawain’s journey back to Camelot is filled with difficulty, but he and his horse finally return home to a hero’s welcome. Wearing the green girdle as a sash, he tells all about his adventures and failures. King Arthur and his knights have a different point of view: rejoicing in Gawain’s goodness, the green girdle will be also worn by his best knights as a sash symbolizing their value as Arthur’s knights. And the poem ends.

Back Home

Gawain may be the most virtuous knight in the realm but now his pride has been dealt a mortal blow. He (and we) correctly sees himself more like you and me than some kind of hero, yet he must also maintain this role in King Arthur’s court. At the end of the poem Gawain is still the virtuous knight in the eyes of his companions and King, but he knows better. He has been introduced to the basic asymmetry we all experience between outer reputation and one’s perception of oneself. Gawain will have to find his own solutions and finally embark on his own spiritual journey, for no longer can he rely on others.

During the solstice season Gawain’s fear of death, his love of life, and his role as a virtuous hero were tested by the wild and magical being who we see as a wise man at the poem’s end. A year ago, the wild knight intruded upon the New Year festivities among a complacent kingly court. The year concluded with festivities that were more sinister and contained hidden tests of desire, courtesy, and judgment. It was a test of light by darkness, one that brings about a new light and a New Year, and the poem ends with Gawain a fundamentally changed man.

For many of us the “holiday season” is a time of jumbling and confused perceptions and emotional responses. Often we revel in our close friendships and family connection and it’s also a time when we chew on our own aloneness. Our losses and regrets loom larger. A festive spirit sometimes seems exhilarating, at other times it’s entirely too much. Our collective journey into greater light coexists with a personal journey into darkness. When we re-emerge we’re more complete but with fewer illusions about ourselves and others. We are now ready to venture forth into a year that’s unknown but still entirely will be too dark and too cold. We have seen all these qualities in this great poem from the fourteenth century. For all its strangeness, or perhaps because of it, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight stands strongly with the other great literature of the solstice/New Year season.

[1] Tolkien, J.R.R. and Gordon, E.V. (eds.), revised by Davis, Norman Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, 2nd edition, (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1967); Howard, Donald and Zacher, Christian, Critical Studies of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, (South Bend, In: Notre Dame Press, 1968)

[2] Armitage, Simon, trans. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, (New York, W.W. Norton, 2007)

[3] Merwin, W.S., trans. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2006)

[4] Boroff, Marie, trans. and Howes, Laura (eds.), Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, (New York, W.W. Norton, 2010)

[5] Hannah, Ralph III, “Unlocking What’s Locked: Gawain’s Green Girdle” in Borroff, Marie and Howes, Laura. (p. 144-158). Hannah contrasts the static and remote quality of the pentangle’s symbolism with the changing and dynamic attributes given to the girdle.