The Wife of Bath from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, was, and continues to be, one of Chaucer’s most vivid and enigmatic creations. Lately I have revisited her Prologue and Tale, her character, circumstances, and use of astrology alongside and of the commentary from the previous century. Holding in mind one scholar’s interpretation of the astrology behind the Wife of Bath, I want to present her astrology that reflects more of her character and circumstances. Her depiction and the story she tells seem to stand up well to contemporary feminist and neo-Marxist criticism, diverging from the moralizing tendency we see with older critics. Yet she remains a disturbing character who defies ideology,

The Wife of Bath from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, was, and continues to be, one of Chaucer’s most vivid and enigmatic creations. Lately I have revisited her Prologue and Tale, her character, circumstances, and use of astrology alongside and of the commentary from the previous century. Holding in mind one scholar’s interpretation of the astrology behind the Wife of Bath, I want to present her astrology that reflects more of her character and circumstances. Her depiction and the story she tells seem to stand up well to contemporary feminist and neo-Marxist criticism, diverging from the moralizing tendency we see with older critics. Yet she remains a disturbing character who defies ideology,

Although his Middle English looks and would sound quite odd to us, I tend to look at Geoffrey Chaucer as an honorary contemporary. Depicting a story-telling contest among representative people on a pilgrimage to Canterbury, Chaucer captures a range of personal perspectives and poetic styles, is quick to point out hypocrisy and bad behavior and shallow and true nobility of character, often leaving the reader guessing when he’s being ironic and when he is being serious. Throughout this incomplete work, Chaucer displays a generous nature and encompassing vision of human life.

Although his Middle English looks and would sound quite odd to us, I tend to look at Geoffrey Chaucer as an honorary contemporary. Depicting a story-telling contest among representative people on a pilgrimage to Canterbury, Chaucer captures a range of personal perspectives and poetic styles, is quick to point out hypocrisy and bad behavior and shallow and true nobility of character, often leaving the reader guessing when he’s being ironic and when he is being serious. Throughout this incomplete work, Chaucer displays a generous nature and encompassing vision of human life.

Like Dante from his previous century, Geoffrey Chaucer lived when astrology was a routine part of astronomy, medicine, and psychology. Dante’s use of astrology was general and cosmological. Chaucer used astrological symbolism allegorically, to depict appearance and character, to depict the course of maladies and illnesses, and, in one passage, to note a terrible time to set sail for an arranged marriage. It is not coincidental that the Wife of Bath, a character from the middle classes who is not defined by her work, who discusses features of her natal chart.

The General Prologue’s Wife of Bath

We meet her early in The Canterbury Tales, in lines 445-476 of the General Prologue. We learn that she has a hearing problem. (She will tell us later how that came about.) She has such skill in weaving and making clothes that  she surpasses the Belgians and Dutch who were known for such things. Interestingly Chaucer doesn’t follow this up subsequently. In fourteenth century England women had few ways to make their own living. We also find out that she had been married five times; we’ll be hearing much more about her marriages from her.

she surpasses the Belgians and Dutch who were known for such things. Interestingly Chaucer doesn’t follow this up subsequently. In fourteenth century England women had few ways to make their own living. We also find out that she had been married five times; we’ll be hearing much more about her marriages from her.

She is well dressed, overdressed with kerchiefs wrapped around her, broad skirts and a good pair of new shoes; her red stockings red seem to match her ruddy complexion. Continuing this hint of Mars, if someone else tried to be the first at offering during the church ceremony “…certyn so wroth was she,/That she was out of alle charitee.” Her dress and discourse are all extravagant, perhaps audacious. As we’ll see when she speaks for herself, she would not strike one as pious in a conventional sense, even if she has been on pilgrimages to Jerusalem and important pilgrimage sites in Europe.

She also has a gap between her teeth, a sign of a strong sexual nature. She also seems to be good company to others on the journeys.

In felawschipe wel coude she laughe and carpe [talk, chat].

Of remedyes of love she knew per chaunce,

For she coude of that art the old daunce.

Where She Fits In

Based on the curre nt consensus, the Wife of Bath is the sixth individual in the pilgrimage company to speak and tell a tale. She begins to speak once we’ve gone through the semi-ironic heroics of the Knight’s Tale, the coarse Miller and his very funny story, the descending quality of the Steward’s and Cook’s stories, and the theatrics of the Man of Laws tale that depicts a long-suffering often-victimized woman who finally finds home and happiness. At this point needs to bring in a different point of view: the Wife of Bath feels the need to be heard.

nt consensus, the Wife of Bath is the sixth individual in the pilgrimage company to speak and tell a tale. She begins to speak once we’ve gone through the semi-ironic heroics of the Knight’s Tale, the coarse Miller and his very funny story, the descending quality of the Steward’s and Cook’s stories, and the theatrics of the Man of Laws tale that depicts a long-suffering often-victimized woman who finally finds home and happiness. At this point needs to bring in a different point of view: the Wife of Bath feels the need to be heard.

Many other characters give short prologues before they launch into their tale, but the Wife of Bath far surpasses the others in length, taking over eight hundred lines of the Wife of Bath mostly talking about herself. Think of somebody you know who is outrageous maybe in a flirty kind of way, who talks incessantly about herself and her opinions and gives details about her that you don’t what to know, but is interesting and entertaining. To me Chaucer’s character seems to be partly Joan Rivers, partly Rosanne Barr. Her Yet her depictions of battles of the genders seem true even to this day, yet there seems to be something shallow and saddening about this woman – and not from just living in less liberated times.

Experience and “Auctoritee”

The Wife of Bath’s long monologue begins – and continues for about two hundred lines – defending her right to speak about the pains and woes of marriage. She first says that experience is the best authority, but then she cites scripture to promote the virtues of the married life, her robust sexual activity, and her hedonism.

“Authorities” on Chaucer, particularly D. W. Robertson in a Preface to Chaucer (1962), point out how the Wife of Bath misquotes, takes out of context, and distorts scripture to persuade others of the worthiness of her life choices (p. 317-331). As no knowing reader of Christian scripture, I’ll take Robertson at his word. Robertson never asks why would she do this. In my view, Chaucer is showing us the only means by which her opinions would be taken seriously. Citing “authority” was the way to assert authority and she knew it. Experience is not the best authority after all.

Robertson thinks that her style is mostly bad rhetoric if not outright dishonesty. Yet during this time in history, for somebody of her gender and in her social class, there were few if any opportunities for the education that would allow one to be an “authority” on a matter of importance. This would be reserved for the well-born or men pursuing ecclesiastical careers. It’s likely that her scripture learning was from listening to (male) preachers who had their own axes to grind. If the Wife of Bath distorts scripture I’m sure there were many other examples of bad preaching in Chaucer’s day. During her long monologue, other characters on the pilgrimage refer to her discourse as preaching, and even imply that she’s doing a good job.

We also see this from the classical “authorities” cited from her last husbands’ book of the wickedness of wives. In addition to Samson’s loss of hair she tells us of the wives of Heracles, Socrates, Agamemnon, Amphiarius the prophet, and many others, who caused unhappy or tragic consequences to their marriages – for the men. By her own admission she could not cite classical authority on men mistreating women but instead she grabs the misogynous book, cast a few of its pages into the fire, and in return received a blow on the head that would result in her deafness. Yet the woman prevailed and in the end and she forced him to destroy the book.

In a move that would excite the modern astrologer, the Wife of Bath twice cites Ptolemy who influenced the astronomy and astrology of Chaucer’s era (lines 182-3, 323-328). She hails him as an authority yet incorrectly cites his Almagest, a very difficult work of astronomy, unreadable to almost everybody but specialists. Aside from being incorrect, this seems an example of scholarly name-dropping to give her voice a patina of authority.

All this contrasts with her common-sense approach without the scholarly pretensions. This is exemplified by her response to St. Paul’s discussion of “chastity” – that’s fine for those who are so disposed, who may have exceptional holiness, but many aren’t like this – including her – and they also have a place in God’s creation. In other words, it takes all types to make up a world.

Before we look at astrological symbolism that may relate to these issues, let’s look at what she says about her astrological chart and why it matters.

Taurus and Mars and Venus

To spare the reader an overly long passage of Middle English, here are lines translated by Burton Raffel (2008) that speak of her astrological indicators.

I’m truly born of Venus, most certainly,

In all my feelings, but my heart belongs to Mars.

Venus gave me desire [my lust, my likerousnesse], and all the parts

I needed, but it was Mars that made me daring [hardynesse].

My astral ascendant was Taurus, with Mars sharing

The sky. Alas, alas! that love should be sinful.

I followed the path my stars placed me in,

I had no choice but to be what I have been.

I never was good at holding back: my chamber

Of Venus was open to any man who was able.

And yet, remember, I wear Mars on my face

And also in another private place. (Lines 609-620).

For decades, the “authority” on her astrology has been Walter Curry whose essay on the astrology of the Lady of Bath (1922) needs revision. Curry quotes a traditional description of somebody with the first face (first ten degrees) of Taurus rising: “She shall be inconstant, changeable, speaking (or gossiping) with fluency and volubility, now to this one now to that…This sign shall give her a mole or mark on the neck near its juncture with the shoulders…” Those who have studied William Lilly’s Christian Astrology may also remember his emphasis on markings on the face and body. Mars close to the Ascendant would certainly account for a mark somewhere on the head.

Curry notes, and I agree, that both Mars and Venus have placed their “marks” on her, but my appraisal of her expresses a different astrological configuration. In my view, Curry takes it too far by asserting that Venus is also in Taurus and is afflicted by a conjunction with Mars. This would result in a character that is aggressive and disagreeable character and in the deforming marks on her face and on private parts. There is nothing in this text that tells us that Venus is conjunct Mars.

Perhaps it’s a matter of taste, but to me the Wife of Bath is more attractive than in Curry’s accounts. In the General Prologue (line 460). Chaucer depicts her appearance thus: “Bold was hir face and fair and reed of hewe” (my italics). The men on the pilgrimage seem to like her, and she did attract five different men to marry her! Although she eagerly admits using sexuality to assert a power relationship between her and the men she married, she also wants to love and be loved for its own sake. To me this is a strong Venus but one not afflicted by a malefic. If we consider Venus, the ruler of her Taurus Ascendant, instead to be in good condition, we are left with a dialectic between Venus and Mars that works well to reveal her character and her conflicting attitudes toward life, especially men.

I have found a chart that appears to conform to this description and could be a fifty-year old woman in the last decade of Chaucer’s life when he was writing The Canterbury Tales. Because the reference is not a historical but literary work, a hypothetical chart seems appropriate to the occasion. Because I’m an astrologer not a literary scholar, my interest is in using an astrological chart to cast light on a literary work and a literary work to cast light upon a good use of astrological symbolism.

As you can see Taurus is rising and Mars is conjunct the Ascendant. What would give the Wife of Bath the nature of Venus, however, would be Venus in a strong sign and a strong house governing the Ascendant – like exalted in Pisces in the Eleventh from Taurus rising.

A Venus-like person, with a dignified Venus, would be fond of love and sex, music, art, social occasions and parties and luxury – the good things in earthly life. These all seem true for her, but they are also corrupted by the strong influence of Mars on her personal style. At times, she seems anything but charming but instead comes off as rough, coarse, and aggressive. She appears to have little sense that her power politics of the bedroom may be causing her partner unhappiness that will rebound on her, or that her seething anger violates her sense of herself as a loving person. Like some other characters in Chaucer’s poem, sex is not an expression of love but is a simple and impersonal instinct or a weapon to dominate others. Yet, for all this, the Wife of Bath has much appeal and would be an entertaining dinner and drinks companion, no doubt.

Mercury and Venus, Exaltation and Fall

The Wife of Bath’s discourse bobs and weaves but often lands on her last marriage with the young clerk Jankin, the one who had read and quoted from his book of wicked women. She notes, quite fairly, that if women wrote as much as clerics, then we would be reading much more about the wickedness of men. Then she gives us a little astrology. Here’s Burton Raffel’s translation of lines 697-710.

The signs of Mercury and Venus produce

Two very different kinds of human youths,

For Mercury favors wisdom, and loves all science,

While Venus loves good parties, and huge expenses.

And simply because their marks are wholly opposed,

One being down will drive the other up.

Thus Venus rules when Pisces is climbing high,

And Mercury lies flat, helpless, deprived.

And Venus falls when Mercury is rising.

Clerics can never praise a creature of Venus,

And when these clerics grow old, and cannot do

Much more of Venus’ work than their old shoes,

They sit themselves down, and write in their helpless dotage

Books about women unable to preserve a marriage!

Where Venus is exalted Mercury is fallen (Pisces) and where Mercury is exalted Venus is fallen (Virgo), giving us a basic opposition of values of a Venus nature – sensual, loving finery — and those of a colder more cerebral Mercury nature like her young clerk husband. We could say that Jankin is “the Virgo” of this match.

In the astrological chart we have been using, the Wife of Bath’s Mercury is in fall in Pisces and is in a close sextile to Mars in the First. She pivots into anger several times in the prologue and at the end of her story; you can see Mars intruding on her discourse that is trying to be the more like Mercury. She tends to distort facts to support her fixed point of view and she does so quite forcefully. Her rambling but energetic presentation supports Mercury in her chart in a difficult sign in aspect to Mars. By her own admission, she is not one for Mercury’s logic and wisdom; unfortunately, it’s the only game in town for her to be taken seriously.

There are other factors to note in this chart. Jupiter in the Seventh, in trine to Venus, have given her five marriages that have placed her in a better and better financial position. Now, although she has become older, she is confidently looking for Husband #6 – perhaps on this very pilgrimage to Canterbury.

What might one make of Saturn at the Midheaven? The Wife of Bath justifiably feels cheated by the world, by male institutional authority that keeps women in a subordinate position, where the world does not make good use of this women’s many gifts. Mars in the First is applying to a dignified Saturn, and Saturn itself is in the sign of Mars’ exaltation. The Wife of Bath is a powerful and assertive woman but also bitter.

“Sovereynetee”, “Maistrie”, and Her Story

Citing internal evidence, commentators on The Canterbury Tales frequently mention that Chaucer first gave the Shipman’s Tale to the Lady of Bath. Affixing this tale to her long prologue would have given us a different portrait of her, for the Shipman’s Tale coldly demonstrates the interchangeability of sex and money in a story where all the characters get something they want – either money or sex – and highlights how cleverly the lustful monk and the attractive but poorly-funded wife can manipulate each other while the husband remains clueless. Chaucer improves on a story from Boccaccio in a way that the older writer would have admired.

Instead Chaucer has the Wife of Bath tell a romance (sort of) in a way that continues to demonstrate her character: its wit and its pathos. Her telling this story is like an actor who becomes more himself or herself in a dramatic role, or like a storyteller who can tell about heroics he or she could never accomplish in real life. Her story, so different in tone from her monologue, shows the Wife of Bath transcending her own limitations through her adventure in imagination – for a time. Five hundred years before Freud, Chaucer gives us her fantasy to help us understand her further.

Astrologically we’re in the realm not of Mercury, Venus, or Mars but the Sun. Sun is the planet of sovereignty, mastery, governance.

In King Arthur’s time (when there were fairies and the like) a knight rapes a maiden and is sentenced to death for his crime. The matter is taken to the queen who also pronounces a death sentence – in a year. The knight has a year to inquire around what it is that women most want and if he gives the right answer his sentence will be commuted.

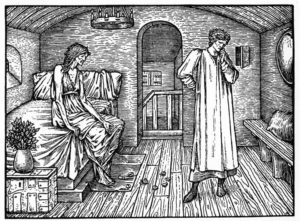

For a year, he wanders the land and receives many answers, none of them satisfactory. Finally, with time running out, he finds an old woman, ugly and old and impoverished, who will give him the answer, but then she gets her reward. The following day the knight returns to the court and tells the queen and the assembled women that what women want is “sovereynetee” over their men, mastery over their lives. Everyone agrees that this is indeed what women want, the knight’s sentence is commuted, then the old woman demands her due – that he marry her and love her forever. The following morning there’s a quiet ceremony, the knight hides during the day but alas at night he must arrive at the marriage bed. No longer able to delay further, the knight is despondent and complains to the old woman that her appearance is foul, she’s too old, and she’s clearly from peasantry and of inferior social standing.

For a year, he wanders the land and receives many answers, none of them satisfactory. Finally, with time running out, he finds an old woman, ugly and old and impoverished, who will give him the answer, but then she gets her reward. The following day the knight returns to the court and tells the queen and the assembled women that what women want is “sovereynetee” over their men, mastery over their lives. Everyone agrees that this is indeed what women want, the knight’s sentence is commuted, then the old woman demands her due – that he marry her and love her forever. The following morning there’s a quiet ceremony, the knight hides during the day but alas at night he must arrive at the marriage bed. No longer able to delay further, the knight is despondent and complains to the old woman that her appearance is foul, she’s too old, and she’s clearly from peasantry and of inferior social standing.

In response, the woman delivers a long discourse on “gentilesse” (better rendered as “nobility” in modern English), a presentation superior to any arguments in the Wife of Bath’s prologue. The old woman presents her ideas in an ordered and coherent way, citing not only the Bible and Christian Dante and Boethius, also classical “authorities” like Seneca and Juvenal. She’s accurate and her speech works as rhetoric and as learned. It’s an accomplished version of who the Lady of Bath would want to be.

You probably can guess or already know what happens next: the woman offers the knight a choice. She can be beautiful but cannot guarantee that she will ward off the advances of men, or she can appear as she does but be loving and faithful always. The knight, thus far presented as the shallowest of young men, makes the extraordinary move of offering her the choice. When he affirms to him that she may choose for herself, she promises both options, and when he looks upon her she has become young and beautiful, and they kiss and joyfully rock the bed and live with each other happily ever after.

Back in her prologue, the Wife of Bath recounts a similar scene of being given sovereignty but it’s far less romantic. After she threw some pages of his book on wicked wives into the fire, her husband punched her in the ear and she fell to the ground, unconscious. Jankin, fearing her dead and regretting his action, promises her the sovereignty. She then strikes him back after which she takes from him the governance in their marriage – although she must keep this information from others. She responds by being good, faithful, and true henceforth and their marriage was happy.

The thematic resemblance between these two scenes further illustrates the element of personal fantasy in her telling of the story. It adds poignancy and maybe pathos to her story of her marriages.

Here’s another element of personal fantasy: if the Wife of Bath was forty when she married Jankin, now she’s now somewhat older. It would be more difficult to find husband #6 since her appearance is perhaps closer to the old women than the beautiful young woman at the end of her story. If in the story the woman can have it both, be both wise and beautiful, the Wife of Bath cannot.

Chaucer’s Coda

Just in case we are beginning to romanticize the Wife of Bath the poet hits us with its coda, the final words of her tale. It’s common in The Canterbury Tales for the storyteller to end with a blessing and wish that the listeners have fortune and happiness, in line with the communal nature of the pilgrimage. The Wife of Bath ends it differently, and I don’t think the language will be a problem for you. Her attitude may be, for it ends with a curse.

…and Jhesu Crist us sende

Housboundes meeke, younge, and fressh abedde,

And grace t’overbyde hem that we wedde;

And eek I praye Jhesu shorte hir lyves

That noght wol be governed by hir wyves.

And olde and angry nygards of dispense,

God sende hem soone verray pestilence!

After this romantic tale that displays the Wife at her best, Chaucer engages us to remember the many disquieting things we have learned about her previously. Her two stories of women taking sovereignty end with positive results, but one is in the fairy tale and in the other we only hear from her.

The Lady of Bath’s final words remind us how she used the idea of the “marriage debt” to insist on making her partners work hard day and night to gratify her, and her withholding sex to reassert control or just to make a point. Considering her ostentatious attire, there is another side to husband #4 keeping the money box locked.

The modern reader easily forgets that the Wife of Bath is at best a difficult character. She is indeed ill-suited to a culture that values women knowing their place, responding with calmness to the vicissitudes of life, and not speaking words that would displease men. We cannot respond to her wholly negatively as do some “authorities” of the previous century, nor can we modern people think of her as merely victim of an oppressive social system. Chaucer has given us a portrait of a person and a culture that will continue to intrigue and frustrate his readers for a very long time.

It can be fun and interesting to see how times and dates picked ‘at random’ in books and movies will often reflect what’s going on in the story when an astrological chart is drawn.

I did this with one of my favorite movies, Agnes of God in which a young nun (Meg Tily) becomes pregnant and kills the baby right after its birth in her convent room. A psychiatrist, played by Jane Fonda, is assigned to see if she is ‘sane’ and ends up unraveling the mystery of what happened to Agnes and why. Anne Bancroft plays the scrappy abbess of the convent.

Without going into too much detail, we learn that the baby was conceived on the night of January 23, 1984 in a convent about 30 miles north of Montreal, Canada in a town called Berthierville.

I took the average length of the human gestational period and arrived at October 15, 1984. The baby was born at night, after the nuns were in bed. We learn that they retire at about 9pm, so I picked 10pm as the birth time. The chart that popped up on the screen was surprisingly appropriate. The Moon was rising in Cancer and in opposition to an extremely close Mars-Jupiter conjunction in Capricorn, right on the descendant and of course opposite the ascendant. Mars rules the 10th of the mother and Jupiter the 9th of religion and monasteries. The unknown father is ruled by Venus in detriment in Scorpio with Saturn.

In the opening scene, it is several weeks after the birth and death of the baby (early November) and Dr. Livingstone (Jane Fonda) declares that it’s her birthday. Scorpio is a perfect sign for a psychiatrist and sleuth who becomes obsessed with the case. Later in the movie, we see convent documents that have Sister Agnes’ birth date on it (a Cancer) and Mother Miriam Ruth, the Abbess played by Bancroft. Her sun-sign is Leo. The personalities of all of these characters in the movie ‘fit’ very well the sun-signs that were given to them. Coincidence?

The movie was originally a play by John Pielmeier. If you have never seen the film, I highly recommend it. Again, the data that i ‘came up with’ for the chart of the birth and death of the baby (a girl as it turns out) is October 15, 1984 10pm in Berthierville, Quebec, Canada. There are more things I could say about this chart, but if interested, you can cast it for yourself and take a look, but do so after seeing the movie.

ps–I later discovered that the feast day of Saint Agnes is January 21st, in the story the conception is on the 23rd of January. I do not know if the playwrite was aware of this or not.