These Difficult Times

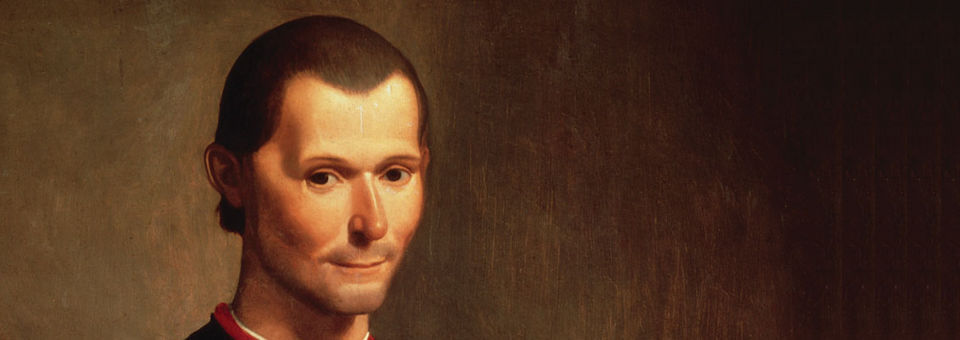

Are also good times to ask fundamental questions about politics and our lives. What is the relationship between personal and political ethics? What are the proper and improper uses of political power and political advocacy? Among the individual, the political unit, or humanity as a whole, is there a basic unit of who we are? As one of the great political voices and ideological builders of the modern age these are times to explore Niccolò Machiavelli and The Prince.

Machiavelli died in 1527 and wrote Il Principe in 1513, just over five hundred years ago. The Prince (not The Little Prince!) was never intended for a general readership but for a specific individual in power, and is probably the most influential job application ever. Disregarded by its recipient but famous after the author’s death, this short work has cast Machiavelli sometimes as the devil and sometimes as a prophet of the modern age. To form your own opinion, here is the opening of Chapter 18 of The Prince.

Machiavelli died in 1527 and wrote Il Principe in 1513, just over five hundred years ago. The Prince (not The Little Prince!) was never intended for a general readership but for a specific individual in power, and is probably the most influential job application ever. Disregarded by its recipient but famous after the author’s death, this short work has cast Machiavelli sometimes as the devil and sometimes as a prophet of the modern age. To form your own opinion, here is the opening of Chapter 18 of The Prince.

“Everybody knows how praiseworthy it is in a prince (read “leader”) to keep faith (read “promises”) and to live in sincerity and not in craft. Nonetheless, we see through experience in our times that those [“leaders”] have done great things who have taken little account of [promises] and have known how to addle the brains of men with craft; and in the end, they have overcome those who have founded themselves on integrity.”

Machiavelli tells his princely reader that it is important that he know how to act like an animal when necessary, using the strength of a lion and the cunning and vigilance of a fox. The effectiveness of a leader is not indicated by the quality of his virtue or instincts of humanity but his intelligence, his ability to adjust to changing situations to do what is required.

Here’s how Broadway and Hollywood make a Musical of Machiavelli

A semblance of virtue and religious faith is often required even when masking one’s true intentions and actual behavior. Additionally, promoting religion is a good way to keep the “subjects” in line although genuine religious or ethical conviction can make the prince less effective and is to be avoided. The Prince also contains the famous question whether it’s better to be loved than to be feared. Both, he says, but if one must choose it’s better to be feared. One cannot accuse the author of naivety – or being wrong.

Who Was This Guy?

It’s difficult to discuss Machiavelli’s life without referring to the complicated political scene of High Renaissance, particularly the changing fortunes of his native city Florence and those who sought to rule the city. Machiavelli was born into a republican family, leaning toward rule by a secular elite, not dominated by a tyrant or a wealthy family like the Medici.

Machiavelli himself experienced two abrupt turns of the Wheel of Fortune. Both were result of the oscillation of Florentine leadership and the forces vying for domination of the Italian peninsula.

Fortune turned upwards when Machiavelli was twenty-nine and obtained a prominent position in a new republic headed by Pietro Soderini. This republic replaced theocratic domination by  Girolamo Savonarola; the Medici had been kicked out five years previously. The ambitious Niccolò Machiavelli was given responsibilities beyond his job description (to the resentment of his immediate boss), and went on sensitive diplomatic missions throughout Italy and to France. His first writings were assessments of the various people and places he visited.

Girolamo Savonarola; the Medici had been kicked out five years previously. The ambitious Niccolò Machiavelli was given responsibilities beyond his job description (to the resentment of his immediate boss), and went on sensitive diplomatic missions throughout Italy and to France. His first writings were assessments of the various people and places he visited.

Fortune’s wheel abruptly changed course fourteen years later. In the autumn of 1512, after Spain and the Papacy began to threaten to overtake Florence, Soderini fled the city and the Medici were invited back. Machiavelli was suddenly without a job. Four months later, when his name appeared on a list of people sympathetic to a plot to overthrow of the Medici, he was arrested, briefly tortured and released but exiled from the city.

Machiavelli was obliged to stay on his family farm outside the city and work the land by day – to his horror. He soon began writing The Prince as an effort to impress the Medici ruler of Florence and be restored to privilege and his native city. The Prince had no effect whatever on his fortunes with the Medici but copies eventually found their way around, going to press only after his death in 1527. He was permitted to return to Florence a few years after writing The Prince and made his living as a writer, not a government official. In a cruel twist of fortune, in the year of his death Florence became a republic once again, he applied for a position, but was rejected because of his past affinity with the Medici.

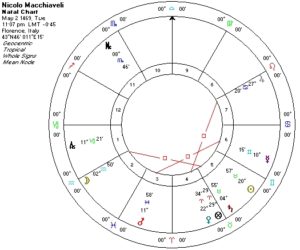

With this information in mind let’s look at his fascinating astrological chart, first presented without outer planets to look at traditional indications.

Natal Chart: Much Saturn and Mercury

Starting with Machiavelli’s Sun sign won’t get us very far, let’s first look at his Ascendant and its ruler and thus we begin with Capricorn and Saturn. You may also notice that Moon is in Aquarius, another sign governed by Saturn and is applying to – you guessed it – Saturn. Saturn is in the positive Firth House and is also oriental emerging from the Sun, an advantage for the “superior” planets. Yet in Machiavelli’s nocturnal chart Saturn is the out-of-sect malefic that, compared to the other malefic Mars, can cause problems. In sum, it’s a favorable Saturn but with a tendency toward harmful excess.

Saturn manifested in different ways throughout Machiavelli’s life: as a melancholy disposition, of a little too much fun separating the ideal from his version of the real, and a philosophical outlook that was uncharacteristically materialistic and atheistic for his time. Although the Discourses, begun at about the same time as The Prince, is more measured and less strident, his attitudes toward people as essentially self-serving and amoral is consistent throughout all his writing.

What is Moon’s contribution? In Aquarius and applying to Saturn, Moon is impersonal, fixed of emotion, analytical, disliking the drudgery of daily life, but also true to his perception of the truth. Unlike much of his advice to leaders and their advisors, Machiavelli had no ability to pretend otherwise from who he was or what he knew.

This is reinforced by the dominance of the fixed mode in his chart: the ruler of the Ascendant Saturn and Taurus Sun and Aquarius Moon. For all his advice that leaders be adaptable, it seems more difficult for the author of that advice.

This brings us to Mercury, Machiavelli’s only planet in in its own sign, in Gemini in the Sixth. Mercury is in its own triplicity, in an air sign in a nocturnal nativity. He was both brilliant and clever and was clearly the smartest guy in any room he walked into – at least after Leonardo and Michelangelo left Florence. Mercury is on the more favorable occidental side of the Sun (for Mercury and Venus) but is slow of motion, moving toward retrograde: this increases his focus although it may bestow less flexibility and improvisational skill than is usual for Mercury in Gemini.

Mercury has a significant square from a strong Mars that is in its own triplicity and in sect in Machiavelli’s nocturnal chart. This combination gives stridency, verbal or mental aggressiveness, and aid in analytic ability. I sense that he would have little patience with all those people less quick-witted, with less mental ability than him. He could be a great dinner guest, for about a half-hour, then discomfort sets in.

There’s more about Mercury – it’s strong relationship to the Lot of Spirit. But first we move onto the Lot of Fortune.

Dame Fortune and Other Women

In the next to last chapter of The Prince, Machiavelli discusses the imperious nature of Dame Fortuna, a condition of our earthly life that moves up and down, brings success and disaster with no obvious relationship in a seemingly arbitrary way. The Part of Fortune is an astrological indicator for this truth about our lives.

Machiavelli’s Lot of Fortune is in Aries with Venus nearby, governed by Mars in Pisces; the Lot of Fortune also has a square from benefic Jupiter. The presence of Venus is usually helpful but it’s a Venus in detriment. The condition of Mars could be helpful but Mars is in the twelfth house to the Lot. Could his fortune be diminished by secret enemies?

Chapter 25 of The Prince recommends anticipating the downward turns of Fortune’s Wheel and preparing oneself for future difficulties when times are good, like a military that continues to train for war when there are currently no threats. Yet when Machiavelli was riding high in the government of Florence, he did not prepare sufficiently for Fortune’s Wheel’s downturns and was left without resources; his ambition and insensitivity made himself more vulnerable to Fortune’s downswings.

Jupiter in Cancer in the Seventh House in aspect to Lot of Fortune would eventually come to Machiavelli’s assistance, when a friend prevailed on the ruling Medici to let him come back to Florence – but as a writer, not a governmental official. Upon his return, Machiavelli did well through his writings that were nonpolitical in nature.

Machiavelli counsels that when facing Fortune directly, it’s far better to be impulsive and aggressive than cautious. In a statement that is justly infamous, Machiavelli says that one should treat Fortune as a woman, handle her roughly and subdue her. This speaks poorly of his view of women even in an era that treated women routinely as commodities. Yes, he was married and had a family, yet by reputation he didn’t let family life limit his sexual activity or his attitudes toward women.

Machiavelli wrote a comedy for the stage, La Mandragola or The Mandrake that manages to combine bribery, sexual hijinks, and church corruption in an ironic farce worthy of Oscar Wilde. Everybody, no matter how virtuous one seems, has his or her price. It’s a play consistent with Machiavelli’s personal and political views and became of one the great successes of the Italian Renaissance stage.

Lot of Spirit, A Stronger Position

If the Lot of Fortune is an indication of the ups and down of our lives, the Lot of Spirit is more about inner attitude and possibility. The Lot of Spirit is symmetrical to the Lot of Fortune with the Ascendant at their midpoint. This creates an important dynamic relationship between the two.

Machiavelli’s Lot of Spirit is in the Ninth House in Virgo, and Mercury, the other ruler of Virgo, is in a Tenth House relationship to Spirit. This gives Mercury an even stronger role in his chart then we previously saw. It also tells us that his main means of asserting himself was through thinking and analyzing, and helps account for his strong – even if self-destructive – independent mind. If Mercury was angular to the Ascendant instead of being in the relatively ineffective Sixth House, he would have been better able to better use his mental abilities on his own behalf.

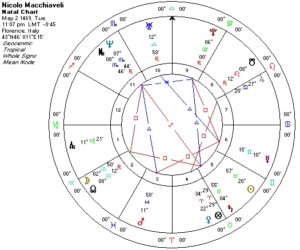

Let’s Bring in The Outer Planets and the Midheaven Degree

We first see Uranus in the Tenth House and first think that Machiavelli’s career took unexpected turns and his participation in the world was different from what he thought or wanted. We also see the close trine from Uranus to Mercury and have a further indication of his strong intellect and lack of caution about turning the previous millennium of political thinking on its head.

More important is Pluto’s square to Mercury: along with the square from Mars on Mercury’s other side, Pluto’s greatly adds to the biting and incisive content of much of The Prince and some of his other writings. Considering his life work and subsequent reputation, how could Pluto not be prominent in Machiavelli’s natal chart?

Neptune has a trine to Mars, perhaps causing him to idealize or romanticize strong military characters like Cesare Borgia and Alexander the Great. Neptune is conspicuously conjunct the Midheaven, a place we have not talked about yet.

What is the role of the Midheaven degree as opposed to the Tenth House of career? In my view the Midheaven degree is more one’s larger participation in the world, what we moderns may call “lifestyle”. We note that in Scorpio the Midheaven degree is governed by Mars and Mars has many roles to play in this natal chart.

The Midheaven degree also culminates with the fixed star Zuben Elgenubi or the South Scale. Like it’s partner Zuben Eschamali or the North Scale, they are of the nature of Mars and Mercury. Although both fixed stars may relate to the larger social sphere, Zuben Elgenubi is considered the more malefic of the two.

Perhaps the best days of Machiavelli’s life was in his role as emissary to Cesare Borgia where he could see first-hand how ruthlessness and effective leadership could go together, how a canny but unscrupulous leader could maybe unite Italy. In retrospect, this seems like Mars (force and strength) and Neptune (sheer delusion).

Machiavelli’s Fifth

When I encounter a person as ingenious as Machiavelli, I liberate myself from my traditional astrologer cave and check out the Fifth Harmonic chart. A Fifth Harmonic can depict one with situational creativity (as opposed to visionary creativity); it can be an indicator of a kind of improvisatory genius.

Here’s his natal chart but now with lines drawn to depict arcs that are multiples of five. Keep in mind that the circle of 360 degrees divides by five into 72 degrees and we’ll be looking at multiples and divisors of 72.

Had I greater visual calculation skills I would have noticed that the Moon at 2 Aquarius is 108 degrees away from Sun at 20 degrees of Taurus; I might have noticed that Saturn at almost 5 Taurus is 36 degrees from Mercury at 10 Gemini. I might have even noticed that Uranus and Pluto are also 36 degrees away from each other.

Why are 108 and 36 important? 108 is 72 – that is the 360-degree circle divided by 5 – and 36 is one half of 72. This means that in a Fifth Harmonic chart you can see Sun-Moon and Mercury-Saturn as tight oppositions.

The prominent Sun-Moon connection in a harmonic chart is often an indication of the importance of the symbolism of that harmonic to the native. Mercury and Saturn bring together his two most prominent planets into close collaboration and display his ability to wed ingenious analysis to social and political realism.

In his Fifth Harmonic Mercury has trines to both Jupiter and Venus, the traditional benefics. How is that? Mercury is separated from both planets by 48 degrees (24 times two and 24 is one third of 72.)

This configuration should add considerable charm and congeniality to his mind and behavior and at closer range perhaps this was so. It certainly contributed to his strong abilities as a writer of prose and drama.

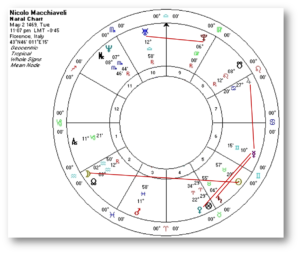

1498 — Fortuna’s Lovely Smile

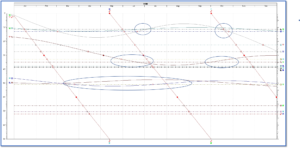

For Niccolò Machiavelli 1498 was a fine year, being elevated to a job for the new republican government. This would give him a chance to be in the middle of politics, to be an important person. Here are his transits for that time, graphically presented.

Remember that this depiction sorts signs and degrees into cardinal-fixed-mutable modes so that intersections between straight dotted lines (natal positions) and moving lines (transiting planets) show transiting conjunctions, squares, or oppositions .

There are many transits relevant to this important year of his life. If we follow the Jupiter line at the top of the page, it’s in Capricorn the sign of his First House, and Jupiter has three passes onto his Ascendant and square to Uranus. Transiting Jupiter onto an Ascendant is an positive transit for one engaged with his world, and the square to Uranus will bring in his unconventional side in a positive manner.

Note the movement of Saturn further down, in Aries at the beginning of 1498 and then in early May moving into Taurus. You will note intersections of that line with Moon in Aquarius, forming a square, and transiting Saturn’s conjunction with Saturn – his Saturn return! Yes, Fortune is smiling on this saturnine ambitious person who is going to get the job that will take the measure of him, finally.

Continuing further down the page, note a station of Uranus in Aquarius in square to his Sun in Taurus. As with many Uranus transits, this had a two-sided quality. On one hand, Machiavelli can step outside of convention and, if on the inside, be an inspirational leader or spokesperson; Uranus can also bring impulsiveness and insensitivity and it’s likely he presented himself as a talented but arrogant young man who couldn’t wait to take on the world.

Machiavelli’s progressions amplify the Mercury-Mars square in his natal chart, for in 1497 Mercury turned direct by progression and made an exact sextile to his progressed Mars. Because Mercury takes its time to turn around and begin to accelerate, this sextile was prominent in his first few years of office.

Hellenistic indicators show his decennials as Venus/Moon although Moon, as the ruler of his Seventh House, may be in position to yield important partnerships and friendships. Certainly Venus/Moon together are an affable combination even for him. More importantly, perhaps, zodiacal releasing from Fortune is Gemini/Virgo, doubly accentuating his strong Mercury as well as his Lot of Spirit in Virgo. Perhaps here’s a time in which he was paid to think.

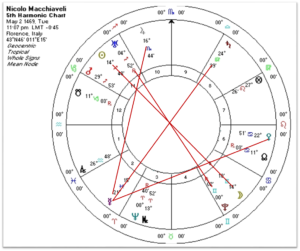

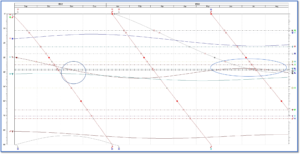

1512-3 – Fortuna’s No Longer Smiling

Machiavelli not only lost his position but was later jailed, tortured for a day, then exiled outside his city. In the fourteen years since landing the perfect job, we would expect Saturn to again be a factor, opposite where it was during better times. But here we have something different. In November 1412, when he lost his job, Saturn was newly in Scorpio, after being in square to his Moon in Aquarius and oppose his Saturn in Taurus, then it began to slow down and conjunct Neptune and his Midheaven degree. So much for his illusions of vocational grandeur.

Machiavelli’s transits for February 1513, when he was arrested, are not notable, although his exile began when transiting Mars was conjunct his Sun. Sure, I bet he was angry, but maybe he was marched out of town by Florence’s constabulary.

What transits happen that summer, when he likely began work on The Discourses and The Prince? They emphasize Saturn transiting his Neptune and MC degree, once again, but this time they are joined by Jupiter in Taurus and Mars in Leo! This adds strength and conviction to otherwise difficult planetary influences. Unlike other famous Florentine exiles like Dante Alighieri, Machiavelli didn’t nurture a decades-long resentment against his native city but quickly began to look for a way back, even if that meant establishing himself in the good graces of the ruling Medici family. It was under this planetary lineup that Machiavelli began his work that would change much of the political thinking of the modern era – and temporarily not do him a bit of good.

Machiavelli’s progressions at that time do not foretell his vocational downfall but his literary resurrection. In 1513 his progressed Mercury was trine progressed Uranus (repeating his natal configuration) and there was a First Quarter Progressed Moon that year, signifying a time of decisiveness. Unfortunately for the short term this meant he worked the farm by day and wrote his masterworks by night.

The decennials for his fall from power were Sun-Sun: this might strike you as odd except for his Sun being in mediocre condition. It was a public downfall. Circumambulations, an early form of primary directions, brought his directed Ascendant to a conjunction with Mars in mid-March 1513 as he was likely packing his bags to leave Florence.

Zodiacal Releasing from Fortune went from Cancer-Cancer to Cancer-Leo at the end of 1513. More interesting are those from Spirit that became Sagittarius/Capricorn in September 1512 and stayed there through most of 1514. Capricorn is, of course, his First House, and, thinking of the meaning of the Lot of Spirit, it’s a good time to do his independent thinking, to find his own mind, not to seek favor from Dame Fortuna.

However, in April 1513, by the time he had hardly fixed up his new bedroom on the family farm, his decennials changed to Sun-Mercury! Any good astrologer would have told him to stop feeling angry (if he was) or sorry for himself and get writing.

Machiavelli’s Voice Today – A Few Important Questions

Was Machiavelli a cynic or nihilist or sociopath? Did he value power for its own sake?

If we define cynical as not holding out too much hope for the virtuous qualities of humanity or human situations, Machiavelli must plead “guilty” to being cynical. I can also make the case that Machiavelli was less nihilist, less sociopathic than, say, some current politicians like Newt Gingrich or Mitch McConnell.

At the beginning of Chapter 15 of The Prince, Machiavelli draws a sharp distinction between how one would like things to be and how they actually are. The virtuous ruler will be at a disadvantage among others who are less virtuous than he. (He may have his former mentor Pietro Soderini in mind.) Elsewhere Machiavelli characterizes people as self-serving and inherently defensive. This places Machiavelli in line with St. Augustine of 1100 years previously and some conservative supporters of “political realism”. (Of course, Augustine was promoting a Christian alternative.) In the sphere of economics, Machiavelli’s view of humankind as motivated by self-interest would become the justification for capitalism a century later.

At the beginning of Chapter 15 of The Prince, Machiavelli draws a sharp distinction between how one would like things to be and how they actually are. The virtuous ruler will be at a disadvantage among others who are less virtuous than he. (He may have his former mentor Pietro Soderini in mind.) Elsewhere Machiavelli characterizes people as self-serving and inherently defensive. This places Machiavelli in line with St. Augustine of 1100 years previously and some conservative supporters of “political realism”. (Of course, Augustine was promoting a Christian alternative.) In the sphere of economics, Machiavelli’s view of humankind as motivated by self-interest would become the justification for capitalism a century later.

Although The Prince is about the acquisition and maintenance of power, the final chapter discloses a goal of uniting Italy and repelling the “barbarian” French, Spanish, and Germans. Machiavelli had a nostalgia for Rome and particularly for the Roman Republic – here he found (or made up) an example of a political state that could improve the lives of its citizens.

Reading “The Question of Machiavelli” (1971) by Isiah Berlin, a political thinker of the previous generation, provides an interesting perspective. Berlin maintains that Machiavelli was not immoral or amoral but used an ethical standard based bringing order and prosperity to a political entity and its citizens. Machiavelli’s was not a unified moral system that would apply to all people and all situations; as follower of materialist Lucretius, he was unconcerned with questions of personal salvation.

Berlin writes, “There is more than one world, and more than one set of virtues; confusion between them is disastrous. One of the chief illusions caused by ignoring this is the Platonic-Hebraic-Christian view that virtuous rulers create virtuous men. This, according to Machiavelli, is not true. Generosity is a virtue, but not in princes…the nature of men dictates a public morality that is different from, and may come into collision with, the virtues of men who profess to believe in, and try to act by, Christian precepts.”

Surveying this year’s political landscape I find Machiavelli’s point of view rather humane, for he subordinates the lust for power to the just political ends of the state. Although frequently abused in history, Machiavelli’s motive is not that of a power-grab for its own sake. Let’s bring this into contemporary life: during the eight years of the Obama administration the Republican leadership was far more interested in discrediting and defeating Obama – and enhancing their own power – than in working to improve the lives of people. Unfortunately, it was a demagogue who has ultimately benefited from this disservice.

Is Donald Trump a “Machiavellian”?

Trump is not a Machiavellian, he’s an Orwellian. Trump’s political content and style updates Machiavelli for our modern age.

Machiavelli would note that Trump has taken to heart the advice that it’s better to be feared than loved. In other areas, he would likely consider Trump not too bright: this American politician has managed to alienate so many that a strong segment of the American populace is intractably opposed to him. Secondly, Trump makes no pretense of being a person of virtue in his public life while keeping his devices secret: Trump’s full character is on display. Machiavelli would find Trump’s personal exhibitionism unskillful at best, self-destructive at worst.

Additionally, it is important that the prince not be seen motivated by financial self-interest but the by good of the people. Trump’s many conflicts of interest suggest that he is ready and willing to compromise national interest for his personal interest.

Additionally, it is important that the prince not be seen motivated by financial self-interest but the by good of the people. Trump’s many conflicts of interest suggest that he is ready and willing to compromise national interest for his personal interest.

More to Machiavelli’s liking is the Christian piety strongly cast by Ted Cruz and Mike Pence, for they have the potential to be true machiavellians. However, it’s testimony to this secular or cynical age that their promotion of “Christian” values, although met with sympathy in some parts of the population, is considered irrelevant by some and is viscerally distrusted by others.

Unlike during Machiavelli’s time, today’s political atmosphere is permeated with an excess of information and daily spin, from advocacy press to the omnipresence of government officials and celebrities in all media. When Machiavelli accounts for the duplicity of the leader in The Prince, there’s always reference to the truth from which the leader deviates and there’s always a reason for the deviation. George Orwell of the last century, having learned well from the propaganda of dictators, coined the word newspeak to describe the “news” of totalitarianism and doublethink for its epistemology. Here’s a definition of the later from his classic 1984. Read this slowly for it conforms perfectly to Donald Trump’s epistemology, if you want to call it that.

“[Doublethink is] the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them… To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just as long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies – all this is indispensably necessary.”

The contemporary practice of doublethink is outside the range of Machiavelli’s genius but not that of George Orwell. Doublethink can be lethal in combination with unfettered self-interest, something we may be seeing with Donald Trump.

Is There a Place for Ethics or Spirituality in Today’s Politics?

In the Discourses Machiavelli makes a strong appeal to the leader who serves to bring improvement to a city or state that has become weak; there is no greater opportunity for glory than to organize a city or state and improve the lives of its citizens.

At the end of Book 1 Chapter 10 he contrasts Romulus who reformed Rome and Julius Caesar who, in his view, ruined it. He talks of two roads, what we might call beneficial and exploitative leadership, then tells us, “One of these causes them to live in serenity and renders them glorious after their deaths; the other causes them to live in continual anxiety, and after their deaths to leave unending infamy for themselves.”

Machiavelli acknowledges much of what we have learned from the twentieth century. First, ruthless dictators eventually find themselves in a continual anxiety: even if they have killed off any possible opponents, there may be others. We have examples of decade-long dictatorships that have rendered their leaders crazy – Hitler, Mao, Stalin and Saddam Hussein come to mind.

Secondly, Machiavelli notes that history’s judgment is extremely harsh toward these individuals who have ruined their societies, either from personal exploitation or apocalyptic or nationalistic ideology. Benito Mussolini, who was a close reader of The Prince, did not let himself be guided sufficiently by Chapter 10 of the Discourses, or forgot them when he struck up his friendship with Hitler.

There is another side to our last century’s misery. Together with its plethora of dictators, it has also given us Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela. Do these political leaders offer a counter-example for the contention that the virtuous and the politically savvy cannot coexist?

is another side to our last century’s misery. Together with its plethora of dictators, it has also given us Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela. Do these political leaders offer a counter-example for the contention that the virtuous and the politically savvy cannot coexist?

Their work was accomplished in an age of rapid dissemination of information and they all served to display occasions of injustice in the larger society. It is unlikely that nonviolence as political strategy would have worked in 1930’s Germany or 1960’s South Africa or perhaps today’s West Bank. Nor in Renaissance Italy was there an air of moral presumption that can be fertile ground for nonviolent activism. Perhaps we live in better times than did Machiavelli.

Machiavelli’s Final Resting Place at Santa Croce’s in Florence. He’s probably turning in his grave.

Gandhi, King, and Mandela became expert political operators, learned how to exploit opportunities, to keep coming back after setbacks, and to work deftly with supporters as well as opponents. If you study their work, you will find a political realism and resourcefulness that would have made Machiavelli proud.

This also keeps open the possibility that the work of Machiavelli can inspire and guide today’s people who would like not just to be virtuous but work with society to improve it. The Bhavagad-Gita or Tao-te Ching might inspire your inner life, but The Prince can be an excellent handbook – along with a few others – for taking your convictions onto the larger stage of political life.

Holy crow!!! What an article, Joseph. That was great. I wish I could grasp it all.