This is the first of two presentations of literary masters from the nineteenth century whose bicentennials are this year. George Eliot, of “Brit Lit” fame, and Walt Whitman, a luminary of American poetry, were both born in 1819. As personalities and in their their literary style they could hardly be more different from each other. Yet they are both exemplary.

You may recognize the name “George Eliot” and your response may not be positive. I recall that in high school the “honors” English class above me had been assigned her short novel Silas Marner and I heard that this was a gloomy and difficult book, one to keep a good distance from. I read it recently for the first time and was appalled that this classic depiction of deception and redemption and moral causation (what we call “karma”) could be wasted on high school students. I figured that her first novels Adam Bede and Mill on the Floss were no more cheerful and only encountered them recently.

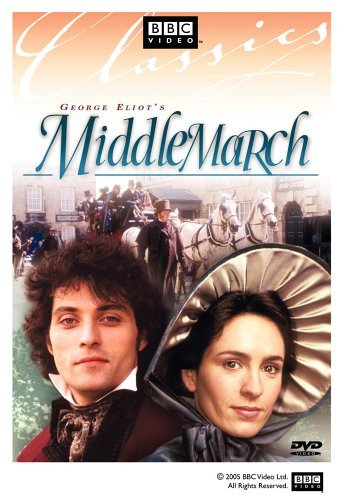

These days she’s best known for her lengthy later masterpiece Middlemarch that has been hailed as one of the great novels in English literature. Many years ago, I was fortunate enough to see a BBC adaptation on PBS and it remains one of the best things I’ve seen on television. Since then I’ve wanted to know more about her and her work; her bicentennial has been a fine opportunity to do so.

Making the Cut

How is that Mary Ann Evans/George Eliot has joined my group of Exemplary Individuals?

Let’s start here: why did Evans began writing her novels under the name “George Eliot”? At that time she wanted her work to be different from what she felt were the mawkish romances customarily written by women of her time. Evans/Eliot felt that her work would be taken more seriously if people thought it was written by a man.

Secondly, she had become the subject of scandal, as she had been openly living with a married man who was separated from his wife who had been living with another man. (Usually extracurricular romances were conducted more discreetly back then.)

When her published fiction, a series of short stories, first came out, Charles Dickens guessed correctly that “George Eliot” was a woman; it later became commonly known that this esteemed new novelist was the same Marianne Evans (she changed the spelling of her first name a few times), the object of gossip in the British literary community and elsewhere. Happily, her being “outed” as a woman with questionable morals didn’t hurt her critical reception or her popularity as a novelist.

As an independently-minded intellectually-inclined “plain” woman who lived when most women were classified according to their marriage possibilities, Evans/George invented and reinvented her life, attempting to reconcile loyalty to her roots with an adult lifestyle among urban intellectuals. She had a respect for the country life she was born into but an attraction (and I do mean “attraction”) to the leading lights of English society.

Her conflicting loyalty gave her a distance from either way of life and became a source of creativity. She had a keen eye toward the provincial narrow-mindedness but also intuitive wisdom and goodness found among ordinary people in daily life. She also understood that everybody has the capacity, regardless of intelligence, “good birth” and purportedly good intentions, for self-deception and narrow-mindedness and to do things that are stupid and eventually harmful. She intuitively understood the law of karma, that the good and the bad we do have consequences that ripple back to us in different ways over time.

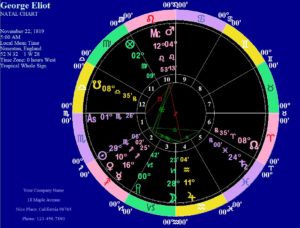

We’ll sample her writing style at the end of this essay but now it’s time to examine her astrological chart and go further into her life.

The Nature of Mars

With Scorpio rising, Sun in Scorpio in the First and Mars governing Scorpio in the Tenth House of career, the strong Mars influence is hard to miss. We see a mutual reception between Sun and Mars, both of which are in the most potent of the angular houses. These two fixed signs Scorpio and Leo, one of element water and one of fire, offer us two ways to manifest a Mars-like style.

We’re all familiar with Scorpio’s reticence and that cliché from your first astrology book that “still waters run deep.” As the sign of both her Sun and Ascendant, Scorpio combines strong determination with an inward-looking nature. In some ways it’s a perfect Ascendant and Sun sign for a novelist: one notices the subtle responses of oneself those around, but you keep yourself hidden from others.

There are some people with whom you always know where you stand. Eliot’s Scorpio influence would not give out this important information to others. She would quietly observe you and later you might wonder if that confused character in her next novel was partly based on you.

Contrasting is Mars in Leo in the Tenth that gives a flair for the dramatic on a public stage. A Mars-like public presence could have worked well for a man during her lifetime or (maybe) for a woman politician during ours. However, Evans/George would have encountered a severe “likeability” problem had more of her true voice been public and she communicated with the public through her writing. Mars displayed itself in her an independent career, earlier as a scholar and later as a novelist. (Happily for the history of the English novel, her partner acted as her literary agent and recruited a sympathetic publisher for her work. With Mars in Leo it still took a village.)

Mars is the medieval “almuten” of her chart and could represent the planet that she most embodied. By far, Mars has the most categories of disposition over Sun, Moon, ASC and MC degrees and the Lot of Fortune. To Mars, the sign ruler of the Sun and Ascendant, we would add this planet as the triplicity ruler of Ascendant and Sun and the term or bound ruler of Ascendant and Moon. Mars is strongly at the helm. Evans/Eliot managed to combine a strong will with subtlety of manner, personal ambition with an eye for personal and interpersonal context.

This was perhaps modeled by her father Robert Evans whose career advanced to the management of large estates for wealthy families: in such a profession, one learns to be competent and very polite in the face of condescending stupidity. In maturity Evans/George learned to conduct herself like Ginger Rogers dancing backwards in high heels, probably “back-leading”.

But – if we attempt to pigeon-hole this woman into simply the nature of Mars, we miss some of the glory of her natal chart. We proceed.

Saturnine Moon and Saturn

In the Third House, in the same sign as the Lot of Spirit, we see Moon in Capricorn, in sect and in its own triplicity or trigon in her nocturnal chart and in close application by sextile to her Sun. Noting also that her Lot of Spirit is in the first degree of Capricorn, Saturn will manifest in many ways in her life and work.

Reading her biography, it’s difficult not to think both of her mother (Moon) and her brother (Third House). Mary Ann’s mother Christiana, the daughter of a local mill owner (think Mill on the Floss), became depressed after two younger twins than Mary Ann died when she was two years old, who herself died when Mary Ann was a teenager. Mother also brought into the household a conservative status-oriented inclination that all of her children, to some extent, kept throughout her life.

Mother’s conservative lifestyle manifested itself especially with Mary Ann’s older brother Isaac, whose affection and acceptance his younger sister sought and never quite obtained. (See Mill on the Floss again.) Isaac made himself historically infamous when he cut off ties with Mary Ann when he found out she had been living with a man legally married to somebody else. Later in her life, after her partner had died and Mary Ann had become legally married to a different man, he finally wrote a letter to her. Isaac attended her sister’s funeral later that year.

Since Moon in Capricorn is also in the Third House/Place of ancient astrology’s “Moon Goddess” and is in its “joy” in that place, and governs Cancer, the Ninth Place of the “Sun God”, we need to look at her intense but ambivalent attitude toward religion. She was raised in a mainstream Anglican community but as a teenager was strongly influenced by one of her teachers who was a Methodist (in those days that was on the rebellious side). She corresponded with her teacher for many years after her schooling but eventually outgrew her.

As a young adult and when her secondary progressed Mercury was at station retrograde, Mary Ann decided not to go to church with her family; this caused a strong rift between her and her father that was only resolved with the intervention of others. All agreed that Mary Ann would attend church with father but could retain her own beliefs as long as she kept them to herself.

When we look at Saturn itself, we are startled by the heavy planetary company it keeps. Saturn in Pisces is very close to Pluto, both of which are in tight square to a Uranus-Neptune conjunction. There are many ways to read this major configuration, one she shares with Walt Whitman who was born five months earlier.

Applied to Evans’/Eliot’s life, the conjunction with Pluto brought a strong dose of intensity and austerity and the squares from Uranus and Neptune added an unorthodox vision – at least compared with the Victorian tenor of her times. Configured with all three outer planets, Saturn also provided a modest and earth-bound opening to the transpersonal.

As a young adult Maryanne became interested in the new German scholarship that applied itself critically to the origins of Christianity – as a historical, not a providential event – and she published some translations of these works from German into English. This helped her develop moral and religious thinking that today we might call “secular humanist”. Her work is full of religious language and imagery, and she represented clergy multi-dimensionally like most of her other characters, yet her vision remained secular.

Her novels increasingly show a moral vision based on the fact that we’re all conflicted people trying to muddle through a messy world yet capable of goodness. George Eliot’s work broke through the tendencies of her age to divide the world into discrete heroes/heroines and villains, instead asserting that we’re all mixed – and mixed up. George Eliot’s works were considered “realistic”, not “romantic” fiction, and her depiction of human nature clearly has Saturnine elements – but also those of Jupiter, our next destination.

The Nature of Jupiter

We begin with Jupiter’s presence in the Fourth House or Place of “Father” – family home, origins, heritage, ancestry. As stated before, despite many obstacles throughout her life, Mary Ann continued to value the spiritual wealth and personal intimacy from her family of origin. Enhancing the positive role of Jupiter in the fourth is a positive sextile aspect from Venus.

The observant modern astrologer may note that Jupiter at 11 Aquarius is but two minutes away from an exact quintile to Sun at 29 Scorpio. This brings together family and father and sense of identity, as well as helped instill a positive attitude that could overcome adversity.

I review her family background. She was the youngest daughter of three whose birth was followed by that of twins who died in infancy. Her father’s marriage was a second one and she had two half-brothers much older than she. In addition to her older brother, Mary Ann had an older sister who was allied with her mother and had a conventional life. Mary Ann was closely attached to father who took care that his “plain” daughter was well-educated, providing tutors after she had finished boarding schools (where she did very well but was miserable being away from her family.)

Later, as Isaac was leaving the family home to pursue his own career and after her sister married and left, it was up to Mary Ann to take care of her now aging father. Robert died when Mary Ann was almost thirty, just after her Saturn return and transiting Neptune was opposing her natal Jupiter in her Fourth House. With its many problems, Evans/George found in her family background the valued landscape of her individual life.

Jupiter, in its relationship with Venus and Mercury in Sagittarius, also gives us information about her career as a writer. Mercury, ruling and in square to her Lot of Fortune in the Eleventh House, disposed by and in sextile with Jupiter, could have made for a jurist or a politician or perhaps a person of business, but these options were closed to her as a middle-class woman of the time. The presence of Venus with Mercury, both sextile Jupiter, could have brought her into the visual arts – something for which she had no background – or a literary career.

Times of Transition

We take up her story after her father died and Marianne went off to Switzerland for a half-year and then arrived in London. Through connections she quickly became part of London’s intellectual community and at the beginning of 1851 had lodgings with John Chapman, who she had met a few years before, who had purchased the liberal Westminster Review and needed an editor and principal writer. This brought her to the front row of London’s intellectual community, and she became acquainted with Karl Marx, Herbert Spencer (more than acquainted, actually), Horace Greeley, John Ruskin, and Florence Nightingale.

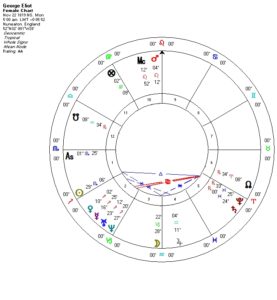

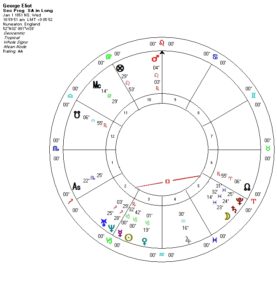

A quick look at her progressed chart for this time tells much. Progressing Sun had just gone into Capricorn and Mercury had been conjunct. Progressed Moon in late Pisces was about to contact her Saturn-Pluto-Uranus-Neptune configuration – things were about to become very different for her. Her decennials at that time were ending a Mercury period with Mercury-Venus, a fine time for friendship, sociability, and more.

At that time she was introduced to the novelist and essay writer George Henry Lewes and they developed a friendship. Lewes had been married several years earlier and had what today we would call an “open marriage”, especially as his wife had a liaison with a friend of his who had fathered children with her. Lewes and his wife could not get a legal divorce.

Lewes and Marianne Evans became closer and by November 1853 she had moved out of the Chapmans and probably by then she and Lewes had become romantically involved. In July of the following year the went to Europe together and, returning home, lived together as if they were married.

Looking at Eliot’s decennials, autumn 1851 had begun a Moon period, with Moon-Moon in play until that autumn when it changed to Moon-Jupiter. This emphasized emotional life in abundance.

Her transits during this time are rather conspicuous. The graphic ephemeris here shows a conjunction of Uranus and Pluto in late Aries and then early Taurus that would first square her Moon, oppose her Ascendant, and finally Uranus would square Mars. Pluto spent a very long time (until spring 1854) going back and forth opposing her Ascendant.

And, to continue this astrological onslaught, transiting Neptune in Pisces was in square to natal Venus in Sagittarius from spring 1852 for about nine months. This could have produced the “love of her life” or grand deception in matters of love. (Fortunately it turned out to be the former.)

We note the disruption in her life’s rhythms (transits to the Moon) and the beginning of a transformative partnership with the transiting planets opposing her Ascendant. Uranus transiting Mars can give rise to a “caution be damned” attitude with its inevitable consequences.

This relationship also helped make her a novelist. The ensuing family and social rejection brought up much in her psyche, and posterity is glad there were no “shrinks” around to psychoanalyze her but instead there were great novels to write. George Lewes strongly encouraged her development writing fiction and, as mentioned before, acted as her literary agent. (When Evans changed her literary name to “George Eliot”, the first name was in homage to him and the last name because she liked the way it sounded with the first name.)

The Rest is History – In Brief

1859-1862 established George Eliot as a writer of great prominence. Her first full-length novel, Adam Bede, came out to great acclaim; Queen Victoria liked it so much that she commissioned some paintings based on scenes from the novel. The next two years saw the publication of Mill on the Floss and Silas Marner. In the subsequent years she wrote a few more novels (including a historical novel set in fifteenth century Florence) and some poetry.

In 1869, as progressed Mercury was in square to Pluto and then conjunct Uranus, she began writing her masterpiece Middlemarch that was originally two different novellas that she combined into one long work. Three years later its length necessitated that it be published in several volumes. The complete work was published in 1874.

In 1878 George Lewes died; they had been together about twenty-five years. George Eliot took his passing hard and secluded herself for several months while she finished some of the work he had left behind. Two years later he married a man much younger than herself in a formal ceremony that finally brought her a letter by her brother Isaac. She died at the end of that year at the age of sixty-one.

Middlemarch, Lunar Heroism and the Modern Age

Many people begin reading Middlemarch but do not get very far – its length, complex writing style and “Greek chorus” commentary can be intimidating and seem dated. More successful have been those who have read this novel slowly over many months that allows one to digest its dramatic nuance and stay with her psychological and moral vision.

To me the strength of this work is its brilliant blending of multiple perspectives showing an ever-changing subjective and interactive dance within a shared world. She combined this with a wide-angled (but also subjective) viewpoint that anticipates much great literature that has followed her.

Bucking the literary trends of her times, there are no heroes or unmitigated bad people in this work, just complicated ones like ourselves. Eliot has replaced the solar heroism/anti-heroism fashionable in her time and ours with that of a lunar nature, where heroics are ordinary, undramatic, and mostly hidden from view.

The end of Middlemarch, in its final two paragraphs, concludes the story of Dorothea who, by the end of the book, has renounced her fortune to marry the man she loves (it’s complicated), and settled down to a life of relative obscurity after having been a “somebody.” This passage sings the song of lunar heroism. They also illustrate her writing style and may help you determine whether her work is your proverbial cup of tea. George Eliot writes:

“Certainly those determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion. For there is no creature whose inward being is so strong that it is not greatly determined by what lies outside of it…

Her finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effects of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Next up: Walt Whitman.