Of all many people profiled in my Exemplary Individuals astrology series, Whitman has had the most influence on subsequent generations. He wrote much and has been the subject of much commentary and scholarly debate. Over the decades his work has been a presence in my life and those of others. The large amount of information about him and the many fascinating features of his astrology merit a more thorough profile than others in this series. Hopefully, as with much of Whitman’s poetry, persistence will pay off for you.

Whitman was the first poet whose work was decisively American and who explored the possibilities of free verse, who battered the boundaries of subjects fit for creative exposition, whose work on the Civil War and the assassination of President Lincoln articulated the feelings of his nation, whose influence we see in modern poetry, film, and folk music, and was one whose style would ramble on like this sentence.

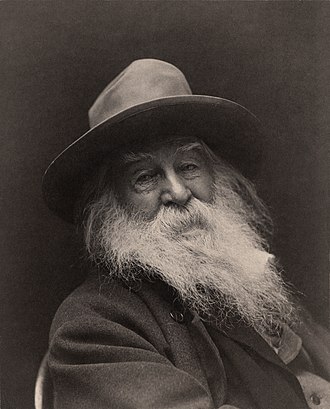

Why is he in this series on Exemplary Individuals? His vision of reality was all-inclusive, embracing our suffering and, like George Eliot born in the same year, the heroism of ordinary life. His spiritual vision expressed itself in his love with the experiment of America and American democracy. He found in its promise a manifestation of human potential, and his age disappointed him as our age disappoints us. I’d like to dine with him in Heaven and he may wear his hat anywhere he likes, inside or out.

We all know that most decisive changes in life take place over extended time, yet sometimes there’s a discrete beginning. In March 1842, on a lecture tour that brought him to New York City, was Ralph Waldo Emerson. His lecture carried the title “Nature and the Powers of the Poet” that would serve as a preliminary version of his later essay “The Poet”. Attending and reviewing for a Brooklyn publication was a young journalist and admirer of Mr. Emerson, Walt Whitman. Walt was twenty-two, a largely self-taught journalist, unclear about his future.

When we look at Emerson’s essay that asks for a new kind of poet for a new kind of nation, these words jump out:

“We have yet had no genius in America, with tyrannous eye, which knew the value of our incomparable materials, and saw, in the barbarism and materialism of our times, another carnival of the same gods whose picture he so much admires in Homer….Our logrolling, our stumps and their politics, our Negroes, and Indians, our boasts, and our repudiations, the wrath of rogues, and the pusillanimity of honest men, the northern trade, the southern planting, the western clearing, Oregon, and Texas, are yet unsung. Yet America is a poem in our eyes; its ample geography dazzles the imagination, and it will not wait long for metres.”

Young Walt Whitman had a progressed New Moon only a few months before in the first degree of Cancer, followed quickly by progressed Sun in square to progressed Saturn. Although Whitman loved being in New York and took easily to journalism, he had many professional and family responsibilities that would burden him for decades. Also active at that time was progressed Mercury opposing progressed Uranus that would aid his increasing unconventionality in the following years.

Uranus also appeared in his transits at the time, in square to natal Uranus, but also Uranus would be in conjunction with natal Pluto and square natal Neptune that year, and in the following year Uranus would square natal Saturn. (We’ll note his strong outer-planet configuration below.) This raises further possibilities for Whitman jumping out of a confinement, even if that confinement manifests in the direction of his mind, not the external conditions of his life.

Transiting Neptune in Aquarius was also conjunct Jupiter: this is a good configuration for grandness (or grandiosity) and idealism. In the spring of 1842, Mars had been transiting the sign Aries that is Whitman’s First House, and this may have triggered some of these outer-planet transits.

Whitman’s solar return for that year, however, is outstanding, Note the strong Mercury-Jupiter opposition, each in their own signs, in close aspect to Moon and Mars in Libra and Neptune in Aquarius. Also prominent is the square between Venus in its own sign and Neptune. The solar return contains many possibilities, including a development of intellect and creative impulse that could reach from the personal to the transpersonal.

At this time there was no hint that Whitman would become a great poet: he wrote some conventional poetry and some fiction and a strange self-help book. None of these were commercially or critically successful.

Fast forward thirteen years after meeting Emerson and the slender book Leaves of Grass came out, a work that, in its many editions, would fulfill Ralph Waldo Emerson’s desires – and go further.

In the Preface to its first edition of Leaves of Grass, Whitman seems to answer Emerson’s exhortation directly. In a poetic vision for his country, Whitman volunteered for Emerson’s description of America’s poet. Here’s from the Preface to Leaves of Grass

“The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. In the history of the earth hitherto the largest and most stirring appear tame and orderly to their ampler largeness and stir… Here is not merely a nation but a nation of nations. Here is action untied from strings necessarily blind to particulars and details magnificently moving in vast masses. Here is the hospitality which forever indicated heroes.”

Whitman continues, emphasizing the non-hierarchical nature of the American spirit, delighting in its openness and nonchalance toward authority, stating that, for example, “…the President’s taking off his hat to them and not they to him – these too are unrhymed poetry.” The nation awaits the “gigantic and generous treatment worthy of it.”

Whitman sent the famous man a copy of his small volume of poetry and received a memorable return letter praising his work and congratulating him “at the start of a great career”. A jubilant Walt Whitman replied in kind to Emerson and never failed to include Emerson’s letter in subsequent editions of Leaves of Grass.

Whitman and Emerson met several times over the next few decades, the latter betraying an admiration for the poet’s talent but finding him embarrassingly “out there”, as we moderns might say. During one famous walk in Boston Commons, Emerson implored the poet to cut out some passages that were too sensual, sexual, or homoerotic. Whitman politely would do nothing of that sort.

Later, when Emerson published an anthology of his favorite poems, none by Whitman were included.

Ferryman and Fellow Passenger

Some of my readers are not enthusiastic about modern poetry and may find themselves baffled by free verse – isn’t it just prose with line breaks? Since Whitman is given credit for developing free verse into an art form, and since not everybody is familiar with the great man’s work, the following will serve as an short introduction to his verse.

His 1856 “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” made a strong impression on me when I first encountered it in college. This poem has made its way into almost every relevant poetry anthology. In this poem a routine part of any commuter’s day is given mythical and spiritual dimensions.

Here’s how it opens

Flood-tide below me! I see you face to face!

Clouds of the west – sun there half an hour high

– I see you also face to face.

These words jump out of the page in five small phrases, each standing alone but in strong relationship to one another. In the simple phrase “face to face” he repeats himself, alludes to a famous Biblical passage that implies a direct encounter with divinity, and brings the reader into the action. Who are “you”, anyway?

Whitman also gives an elemental contrast: the changing water flow is below, the changing sun’s angle is above, and he is in the middle. Later in the poem he notes the visual effect when he leans over the boat and watches the reflection in the water: the area his head is in shadow but the sun’s rays glow around his head – not so differently from a halo that surrounds a holy person in Christian art. Bringing together the elemental (or seemingly trivial) and the divine or universal is a central feature of his verse. Is Whitman also provoking a contrast with the ill-tempered Charon, whose job was to ferry the dead across the River Styx to their eternal locations in the underworld?

It avails not, time nor place—distance avails not,

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence,

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd,

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d,

Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood yet was hurried,

Just as you look on the numberless masts of ships and the thick-stemm’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

The poet is with others but is also an outsider: nowhere in the poem does he describe anybody, nor does he attempt to interact with anybody. He is among them, but he is also their guide, their prophet – and ours, reading him one-hundred sixty years in the future. The poet, the passengers that late afternoon, and we are all playing our great or small roles in life across time.

Typical of Whitman’s verse, this stanza does not conform to a standard meter but nonetheless is full of rhythm aided by repetitive phrases and lines that begin with the same words and follow parallel grammatical structures. Here and elsewhere the cadences show the influence of the King James Bible that was part of his spiritual and literary culture.

Whitman’s use of long lines adds a breathless momentum as the reader seeks the end of a line – or a sentence – and thus a temporary sense of closure. The poet puts his reader in the passenger seat of a speeding vehicle.

The sixth section discusses the “dark patches” that may isolate us within ego yet are also common to us all, that paradoxically serve as a factor binding us together. Note his frequent use of single-syllable words and his tendency to list characteristics as if he’d like to include every possibility. We also see the influence of Shakespeare that also was the literature of his culture.

I am he who knew what it was to be evil,

I too knitted the old knot of contrariety,

Blabb’d, blush’d, resented, lied, stole, grudg’d,

Had guile, anger, lust, hot wishes I dared not speak,

Was wayward, vain, greedy, shallow, sly, cowardly, malignant,

The wolf, the snake, the hog, not wanting in me,

The cheating look, the frivolous word, the adulterous wish, not wanting,

Refusals, hates, postponements, meanness, laziness, none of these wanting,

Along with his sources in the King James Bible and in Shakespeare, and accompanied by his political hero Abraham Lincoln, Whitman contributed to the rhetorical nature of the American English language.

The Outer Mandala of His Life

Whitman’s life is better documented after the first edition of Leaves of Grass than previously. We know that he was born in rural (then) Long Island and his family moved to suburban (then) Brooklyn when he was about four. He was the second of nine children: his older brother Jesse had undetermined psychiatric problems and, when Walt was forty-five, Jesse was committed to in insane asylum and died shortly afterward. A younger brother was alcoholic and suffered an early death. The youngest brother was “feeble-minded” and handicapped and required constant attention and care through his life. I’ve seen nothing about his sisters. As a young person, Walt’s was thought to be self-directed but unreliable.

Walt was named after his father Walter who failed as a farmer and made his living mostly as a carpenter, often moving his family into homes, renovating them, selling, and moving to the next one. Together with the number of children in the family, this created a chaotic and unpredictable household. Walt had a difficult relationship with his father yet was closely attached to his mother. Both sides of the family had a background in the Quaker faith, an unconventional alternative at that time.

Walt’s schooling ended when he was about eleven and he first found work as an office-boy in nearby law offices and later as a printing apprentice. During this time, he was given a library pass and he immersed himself in all kinds of reading. Like many in this Exemplary series, Whitman was primarily self-taught: like the British poet William Blake (included in an earlier profile), this allowed Whitman the space to innovate, to be unconventional.

Walt did some school-teaching in Long Island but didn’t take well to it – he was too indulgent with his young students and not a good disciplinarian. His main occupation during his late teens and twenties was as a printer and increasingly as a reporter and then editor for local newspapers.

Living in Brooklyn but frequently commuting to Manhattan (by ferry, of course), he became politically involved in the anti-slavery cause (although not yet an Abolitionist), wrote much, became an opera-lover (!) and went to many lectures like the one given by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1848, just before his Saturn return, Whitman was fired from a Brooklyn newspaper for his political views and took a job in New Orleans, having been offered a publishing job there. This allowed him to see much of the country and probably during this time he had his first homosexual relationship. During his lifetime Walt had a few gay partners but none were long-lasting. In conformity with the times they were conducted discretely and without much of a paper trail, yet his poetry gives a different impression. His living conditions were modest throughout his life and his personal demeanor was somewhat reserved; again, his poetry gives a different impression.

Less is known about his return to New York where he seemed to work as a carpenter for a few years. Sometime around 1850 he began work on the volume of poetry he would later entitle Leaves of Grass, and developed it over several years.

Chart of Himself

Like much of his poetry, his astrological chart is rich, less transparent than it first appears, and amply rewarding close examination.

Since we know less about his life than his poetry reveals, it seems appropriate to connect features of his astrological chart with passages in the long poem that highlights the first edition of Leaves of Grass that was later titled “Song of Myself”. Here’s a link to the 1892 version. Not only does much of his chart shine through but it’s also a remarkable contribution to literature.

Moon and its Companions

We begin grandly with Whitman’s Moon that is in Leo in the Fifth House. Close to the end of the sign Leo, Moon is close to the fixed star Regulus, the Heart of the Lion, the star of royalty. This is not by zodiacal degree, for their positions are more than a degree and a half apart; their contact is by paranatella or co-rising. At the latitude at which Whitman was born Moon and Regulus rose together that day.

We can certainly talk about his mother with whom he was close; he was clearly her favorite among many children. Seeing that Moon is the ruler of the Fourth House of family and inheritance, we also note the inheritance of his beliefs from his family background. Despite chaos and modest means and difficult family commitments through much of his life, family of origin was a source of strength and confidence for him.

In his poetry and advocacy, he attempted to speak for the nontraditional non-hierarchical nature of America. His strong democratic inspiration is closer to the astrological symbolism of the Moon, the leader of ordinary life, than that of the Sun who symbolizes the central leader and hero. Yet, with Moon in Leo, he was to be prophet and guide, stating often that it is poetic vision, not political policy, that constitutes this nation’s leadership.

Here’s the famous opening of “Song of Myself”. Gone are the supplications to the Muses, common to the first lines of the traditional epic. Gone also is the special heroic person who is sung about. In Whitman’s poem the hero sung about himself – whatever “himself” means. Moon in Leo helps create a combination of solar and lunar qualities that will inspire future generations if not his own.

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here from parents the same,

and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

The Moon’s one close aspect, a trine to Neptune, attests to his interest in opera and theater but also what we might call the metaphysical. He left elaborate conceptual systems to others but strove to make a spiritual and political vision available to others. As a poet, his intuition may have led him to truths that eluded a more careful man of ideas like Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The Sun in Gemini, dispositor of Moon in Leo, is our next destination.

“(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

Whitman’s Sun is at the ninth degree of Gemini, a mere four minutes from eighty degrees from his Moon. The luminaries form a novile aspect or a conjunction in a Ninth Harmonic chart. Often this tells us of a person’s psychic abilities or spiritual inclinations: as nine is three cubed, we’re beyond mere happiness to greater fulfillment. Shortly after the moment of Whitman’s birth the Sun co-arose with the fixed star Aldeberan, the Eye of the Bull. Here’s another of the so-called Four Royal Stars of the Persians. This would incline a Gemini Sun to be more assertive and authoritative, maybe overdoing it.

Whitman’s Sun expresses much of the ordinary symbolism of its zodiacal sign. The air signs deal in different ways with multiplicity. In Gemini, contrasts are not reconciled but reveled in, as myriad possibilities make up a world.

We see a Gemini Sun in his seemingly endless lists but especially his identification with many different people in different situations. Part 33 of “Song of Myself” depicts the fugitive slave, sailor, soldier. It depicts the wounded fire-fighter in lines that became famous in New York City after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

In one passage he depicts a sea-captain saving passengers and crew from disaster. In a fine illustration of Sun in Gemini and Moon in Leo, he begins with these lines: “I understand the large hearts of heroes/The courage of present times and all times”, and ends with “I am the man, I suffer’d, I was there.”

Those influenced by the sign Gemini also tends to stand slightly apart and observe and can have a neutral and sympathetic attitude toward all he or she sees. From section 22 of Song of Myself:

What blurt is this about virtue and about vice?

Evil propels me and reform of evil propels me, I stand indifferent,

My gait is no fault-finder’s or rejecter’s gait,

I moisten the roots of all that has grown.

Since his Sun is also in close sextile to his Ascendant degree in Aries, solar qualities abound. It’s easy to think of Whitman as self-absorbed and egotistic – how else could he use the title “Song of Myself”? Yet he diffuses his solar self into the identities of others, of natural processes, of the cosmos itself, the very large and the very small. He identifies with insects, moss and, in the famous last stanza of this long poem, he instructs his readers to look for him “under your boot-soles.” There’s also my favorite line, “And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels.”

In the stanza of “Song of Myself” in which he gives his name, he presents himself performing the heroic activities of physical life, e.g., eating, drinking, and breeding (he never bred). Many, in his day and ours, have found his poetry embarrassingly self-indulgent and pretentious, yet to me there seems to be a higher agenda that includes what we call ego.

Mercury and Venus (and Jupiter)

Mercury and Venus are in Taurus in the Second House, with Mercury in a close applying square to Jupiter in the Eleventh House. Venus is in its own nocturnal sign, and terms or bounds. We now arrive at what makes Walt Whitman’s work distinct and surprising for the times in which he lived.

Mercury in Taurus, slow of motion having just gone direct, is both his oriental planet and the planet to which the Moon is next in aspect and is thus a strong indicator of profession. We can look his background in journalism and his tendency to supply much concrete detail in his work. Assisting Mercury and giving it a prophetic voice is Jupiter that forms a strong square to Mercury. Jupiter, in Aquarius and in its house joy in the Eleventh, is a universalizing factor, as his Taurus planets revel in what is particular and within the senses.

Whitman was strongly influenced by Emerson’s and Thoreau’s depictions of the outer natural world as a window into divinity. Whitman brought this further: the human body itself provides another window. His expressed love of all sense perceptions, and his glorification the human body and its qualities and functions. In his time, more than now, treatment of sexuality had a wide gap between prudishness and debased pleasure-seeking; Whitman brought human sexuality into artistic expression and into transpersonal possibilities.

More than his homoerotic verse, his celebration of human physicality alienated him from many in “polite society”; his reputation for “indecent” verse diminished his ability to reach a larger audience. A splendid example of the glorification of all things Taurus is in “Song of Myself” #28 — check it out. Here’s something shorter that can go onto a refrigerator magnet.

Having pried through the strata, analyzed to a hair,

counsel’d with doctors and calculated close,

I find no sweeter fat than sticks to my own bones.

Aries Ascending, Mars and His Friends

This may be the natal factor first seen by most astrologers. Aries rising with Mars in Aries in the First House gives the picture of vigor that makes his written work seem to fly off the page – and perhaps overwhelm the reader. Instead of the temperamental assertiveness we usually associate with Aries and Mars, he came across in ordinary life as more reserved, even polite. In his ordinary life Whitman was resourceful and practical, increasingly vocal in his personal interactions, and took on leadership when necessary. His physical presence was more commanding than his outer behavior.

Mars placement takes a trine from Uranus, exact to the degree, and more distantly from Neptune, providing unconventionality and a strong dose of other-worldliness to his Mars placement. Yet these qualities were not naïve, for we find that Uranus/Neptune are also in square to a combination of Saturn and Pluto in the Twelfth House. (We also find from his Saturn-Pluto in the Twelfth House a poetic depiction of the intensity and variety of human suffering, especially in “Song of Myself” and his Civil War poetry.)

Although we find an Aries-like and Mars-like bravado across much of his written work, they exhibit a restlessness coupled with power that is inclusive and non-aggressive, even loving. In some ways his depiction of masculine strength aligns itself well with our current cultural and interpersonal needs. His is a different kind of Mars.

Whitman’s Fifth Harmonic chart shows the influence of the aspect of the quintile in his chart. We see Saturn with greater prominence, as it forms aspects to Uranus, Venus, and Mars. Whitman could be very disciplined and focused in accord with his own agenda. We also see a strong Sun-Mercury trine (twenty-four degrees away from each other) that gives further testimony to his interest in words and communication for self-expression – in his own unique way

Uranus and Neptune in the Ninth House: From “Song of Myself” #32

I think I could turn and live with animals,

they are so placid and self-contain’d,

I stand and look at them long and long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,

They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God,

Not one is dissatisfied, not one is demented

with the mania of owning things,

Not one kneels to another, nor to his kind

that lived thousands of years ago,

Not one is respectable or unhappy over the whole earth.

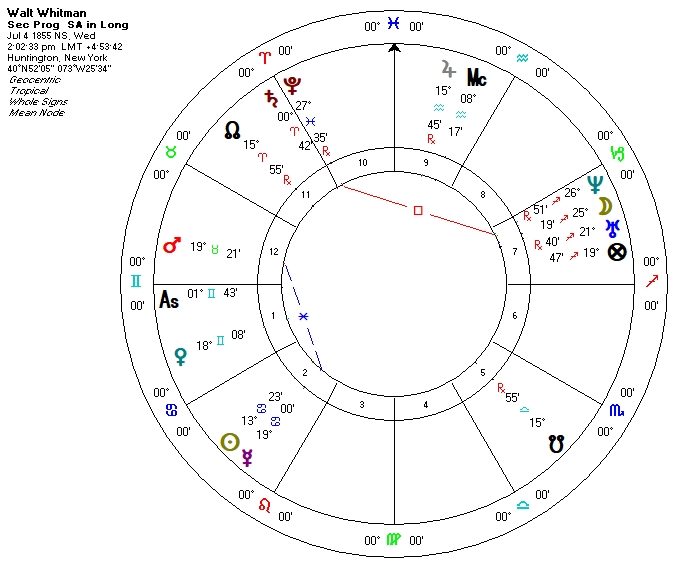

1855-6

On July 4, 1855, the small volume Leaves of Grass – written, typeset, funded for printing, distributed, and publicized by Whitman – came out. Creating more of a sensation that year was Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha that solidified that poet’s reputation as America’s leading bard. If Whitman had illusions of instant fame upon publication of Leaves of Grass, especially compared to Longfellow, he would have been disappointed.

Riding on Emerson’s letter to Whitman, in the following year another edition of Leaves of Grass came out that included poems such as “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” and previous poems saw changes. This was followed by the infamous 1860 edition that contained his most overt sexual and homoerotic passages. These editions slowly brought Whitman greater public attention, much of it negative for his “indecency”, and he continued to work his journalist “day job” to pay the bills.

What were the astrological conditions and circumstances for these times? We will look at a variety of factors.

The ancient technique of decennials is a rotating planetary rulership system. In 1851 the general chronocrator or planetary lord was Mars that would continue for over ten years. However, the specific planetary lord is more important for a shorter span of time, and in late September 1854 this was Sun, followed by Moon from April 1856 until spring 1858. Both luminaries “see” Mars by sign, and both, as we’ve seen, are thematically related to his poetic production. (His major planetary ruler would change to Venus in the autumn of 1861.) Another ancient predictive technique, circumambulations (parent of primary directions and grandparent of secondary progressions) show his Midheaven degree in an exact square to his natal Mercury that signals a greater public display of his writings.

Whitman’s solar return for this year shows enhanced personal expression but not exactly fame. Note Moon rising in Sagittarius strongly connected to Jupiter in its nocturnal sign Pisces. This shows more of a personal than a public presence.

In the mutable sign Sagittarius, Moon rising also shows personal upliftedness and adaptability. In a move often repeated these days, Whitman penned an “anonymous” glowing review of his book for distribution. Looking over the review, I doubt anybody was fooled.

The solar return retains an emphasis on the Sixth House (he didn’t quit his day job). Its Seventh House planets may allude to his making personal connections, as with Emerson and his followers. Note the ruler of his Tenth House of career, Mercury, is strongly placed in Gemini and in the Seventh. It seems that his work would become better known as he connected with specific people, not with the larger public.

Whitman’s secondary progressions show a more permanent change in life. For starters, exact in October of the previous year progressed Mercury was in sextile to progressed Mars that could show strong intellectual activity or communications; this aspect continued to operate through the publication of his first edition.

In 1842, the year he saw Emerson speak, Whitman had a progressed New Moon; The progressed Full Moon took place in 1856, just in time for the second edition.

More immediately to his First Edition, however, the progressed Moon conjunct Neptune was soon to square Pluto: no, this does not make for worldly success, but it can make for a crossing of the proverbial Rubicon. Upcoming and manifesting itself in his “indecent” 1860 edition was progressed Mercury trine Pluto — it’s a fast Mercury that moves direct past the Sun.

His transits for 1855 begin with a final pass of transiting Uranus in Taurus to natal Mercury and the year continues with Uranus in square to natal Jupiter in Aquarius, showing a rather sudden manifestation of unconventional vision. Before moving from Aquarius to Pisces, Jupiter made three passes to Whitman’s Moon in Leo between May and the end of 1855: this can only increase his enthusiasm for reaching a larger audience. One’s outer life is another matter.

For the influence of Saturn was strong. During the spring of 1855 Sun suffered a transiting conjunction of stationing Saturn and a quicker Mars was also moving through Gemini. The finishing processes for Leaves of Grass did not find “loafing and leaning at [his] ease”. Mars moved on, but in the autumn of 1855 and in the spring of 1865 Saturn continued through Gemini transited Uranus, Pluto, Neptune, and Saturn. Indeed, vision is different from ensuing reality.

Whitman and Lincoln

From New York Whitman wrote of seeing the new President as he visited New York. Whitman, like his hero Abraham Lincoln, moved gradually toward abolitionism from a stance opposing the spread of slavery in a larger United States. In the ensuing Civil War Whitman was strongly pro-union.

In 1862 Whitman found out that his brother George may have been injured in the fighting and he went south to find him. After finding his brother he decided to stay in Washington DC and took a variety of office jobs over several years. During the War years, he managed to live very frugally and in his spare hours he worked as a nurse attending to the wounded, and much of his correspondence survives from that time. Although there is no record of ever meeting Lincoln personally, he managed to attend many public events in which the President was in attendance.

Whitman wrote several poems about the war, its initial inspiration and subsequent tragedy for later editions of Leaves of Grass.

There are some parallels between the two men, both being self-educated and relying on the same books that influenced a rhythmic and rhetorical use of the English language. Both spent many young years of their lives among “working class” people and were at ease with a wide variety of people and situations. Taking office after many corrupt pro-slavery Presidents, Whitman had labeled Lincoln the “redeemer President”.

Two of Whitman’s best-known poems responded to the President’s assassination in 1865. The popularity of “Oh Captain! My Captain!”, a very conventional poem for his time, was a source of embarrassment for the poet, yet he continued to include it in subsequent editions of Leaves of Grass. “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” , a truly great and moving longer poem, is a sober meditation on balance of life and death, the process of grieving, and the inevitability of renewal. “Lilacs”, like “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”, displays his mastery of multiple symbols interwoven to create different perspectives.

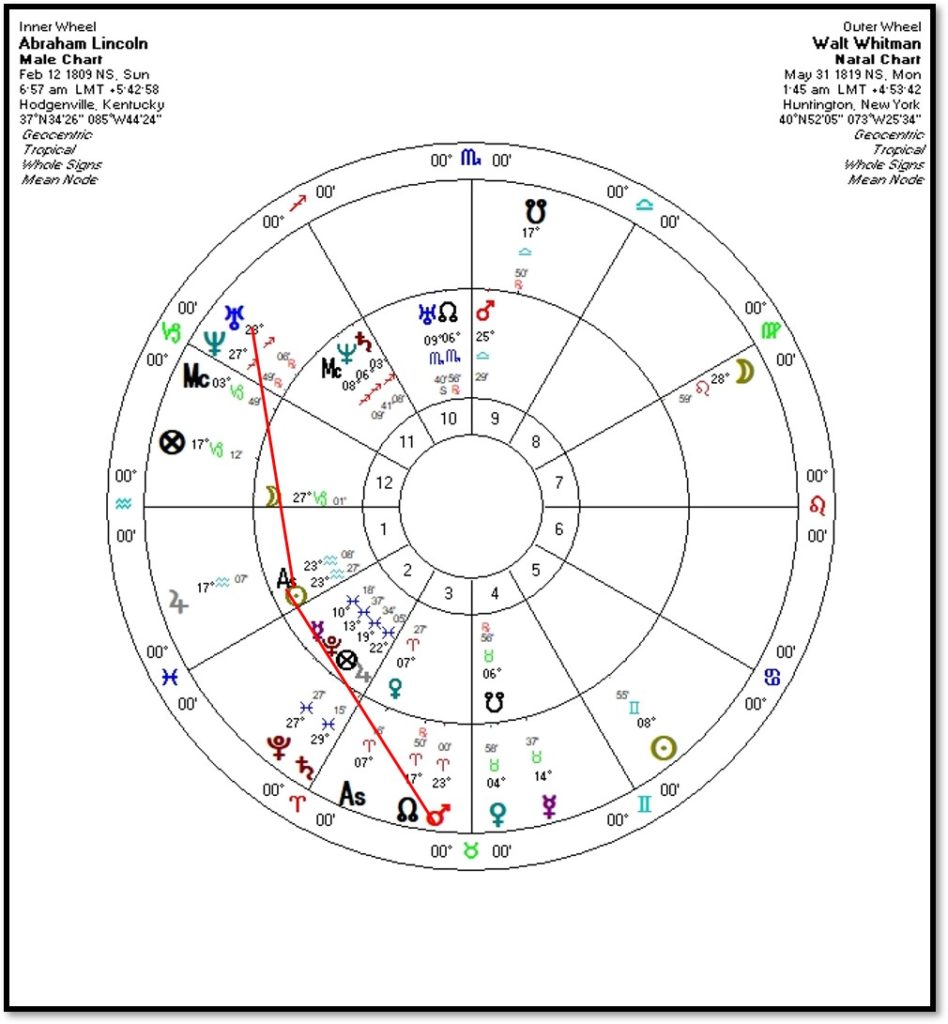

Here’s a synastry that’s a thing of beauty to an astrologer.

Is there an astrological relationship between Whitman and Lincoln? The birth time for Lincoln is given as “around sunup” and his chart has been rectified to place both Sun and Ascendant at twenty-three degrees of Aquarius, in sextile to and bisecting Whitman’s Mars-Uranus trine. It was through Lincoln’s life that Whitman experienced the possibilities of worldly transformational leadership beyond the reach of an otherworldly poet.

Nevertheless, He Persisted

On the personal side, a stroke in 1873 brought about his move from Washington to his brother’s home in Camden, New Jersey, and during the last years of his life lives in a small home he had bought there. Although some students and disciples gathered around him, his health grew gradually weaker and he died in March 1892.

On the literary side, several further editions of Leaves of Grass came out. His work was first appreciated not in American but in England after a sanitized collection of his work was released in 1868 by William Michael Rossetti.

Even with greater fame Whitman sometimes had difficulties finding a publisher, and an attempt to censor an edition from a mainstream Boston publisher resulted in that edition being published in full by a lesser-known House in Philadelphia. He continued to write poetry and to refine further what he had already written up to the end of his life. His later poetry, some of which is excellent, tends to elaborate on previous themes and may show the melancholy that comes with age and disappointment. Appreciation of his work in this country came slowly during his lifetime. He finished the “Deathbed Edition” of Leaves of Grass in 1891, shortly before he died in the following year.

America hadn’t turned out as he wished, becoming too big, centralized, and greedy, yet he never lost sight of its promise and the important role of the poet in establishing its potential and maintaining it. It is ironic that his fame as a central American poet developed as American was becoming unrecognizably industrialized and a world power. It seems that no major American poet since the beginning of the twentieth century has worked without reference or contrast to Whitman’s work and his life and work pervade our culture beyond his wildest fantasies. Yet America continues to disappoint.

He Gets the Final Say

Of great interest to Whitman scholars and devotees is a collection of conversations with Walt Whitman in the final years of his life.

A younger friend named Horace Traubel, who had his own career of note, acted as his private secretary and archivist during the poet’s final years. A recent issue of New York Review of Books has a lengthy article on this important work.

During this time in which some parts of American culture have lost their values that have been reflected in the current government’s policy toward immigrants and migrants, Whitman reminds us that our purpose is loftier than our times indicate.

America must welcome all—Chinese, Irish, German, pauper or not, criminal or not—all, all, without exceptions: become an asylum for all who choose to come. We may have drifted away from this principle temporarily but time will bring us back. The tide may rise and rise again and still again and again after that, but at last there is an ebb—the low water comes at last. Think of it—think of it: how little of the land of the United States is cultivated—how much of it is still utterly untilled. When you go West you sometimes travel whole days at lightning speed across vast spaces where not an acre is plowed, not a tree is touched, not a sign of a house is anywhere detected. America is not for special types, for the caste, but for the great mass of people—the vast, surging, hopeful, army of workers. Dare we deny them a home—close the doors in their face—take possession of all and fence it in and then sit down satisfied with our system—convinced that we have solved our problem? I for my part refuse to connect America with such a failure—such a tragedy, for tragedy it would be.

Leave it to a man with a third house Gemini Sun to have his life turn on his connection with his brother.

Great graphics, particularly the image of the various editions of Leaves of Grass.